For November, it’s that smell of sulfur

We mark the 150th anniversary of Dimitri Mendeleev’s periodic table of chemical elements this year by highlighting elements with fundamental roles in biochemistry and molecular biology. So far, we’ve covered hydrogen, iron, sodium, potassium, chlorine, copper, calcium, phosphorus, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, manganese and magnesium.

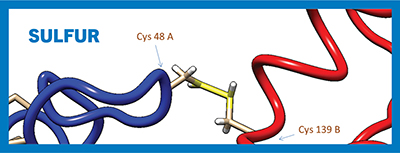

Depiction of the intermolecular disulfide bridge between cysteine residues 48 A and 139 B on opposite chains of the human phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase dimer.Mikejl921/Wikimedia Common

Depiction of the intermolecular disulfide bridge between cysteine residues 48 A and 139 B on opposite chains of the human phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase dimer.Mikejl921/Wikimedia Common

In November, families all over the U.S. celebrate Thanksgiving by eating roasted turkey. During digestion, the proteins in that turkey (and other foods) break down into smaller amino acids that are used by the body’s cells to synthesize its own proteins.

Methionine and cysteine — two of the 20 amino acids normally present in the proteins we consume — are our major dietary source of the element sulfur. The organic compound methysulfonylmethane, or MSM, present in vegetables, legumes, herbs and animal products, is another important natural precursor of sulfur.

With chemical symbol S and atomic number 16, sulfur is a reactive nonmetallic element with oxidation states ranging from -2 to +6. Depending on the environment, sulfur compounds may accept or donate electrons. Sulfur reacts with almost all other elements — except for noble gases — and commonly forms polycationic compounds.

Sulfur is created inside massive stars as the product of the nuclear fusion between silicon and helium. By mass, sulfur is the 10th most common element in the universe — present even in many types of meteorites — and the fifth most common element in the Earth. Natural events such as volcanic eruptions, hot spring vents and tidal flats emit abundant sulfur that later accumulates either as pure elemental crystals or as sulfate and sulfide minerals and rocks.

In most ecosystems, the weathering of ore minerals releases stored sulfur that reacts with the oxygen in the air to produce sulfate particles. Sulfate is assimilated by plants and microorganisms and converted into essential biomolecules such as vitamins and proteins, subsequently moving up the food chain. Sulfur is released back onto the land either by decomposition of organic matter or in rainfall. Terrestrial sulfur drains into water systems, where it cycles through marine communities or deposits in deep ocean sediments.

Some anaerobic bacteria in human gut flora can oxidize organic compounds or molecular hydrogen as an energy source and use sulfate instead of oxygen as the final electron acceptor during respiration. These sulfate-reducing prokaryotes often produce hydrogen sulfide, which causes intestinal gases and flatulence in humans.

In stark contrast, some microorganisms, such as green and purple sulfur bacteria, can use reduced sulfur compounds, and even elemental sulfur, as an energy source to produce sugars by chemosynthesis, using oxygen as the final electron acceptor. Giant tube worms that live on the Pacific Ocean floor rely on these bacteria to feed on seawater sulfide.

Plants and bacteria use environmental sulfate for the synthesis of the nonessential amino acid cysteine. Mammals also can synthesize cysteine from the glycolytic intermediate 3-phosphoglycerate, but they use methionine — an essential amino acid that must be ingested — as the supplier of the sulfur atom. Neighboring cysteine residues in peptide chains can form covalent disulfide bonds that contribute to protein flexibility and control protein structure and assembly.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.