For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

Hemoglobin is a tetramer that consists of four polypeptide chains. Each monomer contains a heme group in which an iron ion is bound to oxygen. In iron-deficiency anemia, the heart works harder to pump more oxygen through the body, which often leads to heart failure or disease.We are celebrating the 150th anniversary of Mendeleev’s periodic table by highlighting one or more chemical elements with important biological functions each month in 2019. For January, we featured atomic No. 1 and dissected hydrogen’s role in oxidation-reduction reactions and electrochemical gradients as driving energy force for cellular growth and activity.

In February, we have selected iron, the most abundant element on Earth, with chemical symbol Fe (from the Latin word “ferrum”) and atomic number 26.

A neutral iron atom contains 26 protons and 30 neutrons plus 26 electrons in four different shells around the nucleus. As with other transition metals, a variable number of electrons from iron’s two outermost shells are available to combine with other elements. Commonly, iron uses two (oxidation state +2) or three (oxidation state +3) of its available electrons to form compounds, although iron oxidation states ranging from -2 to +7 are present in nature.

Iron occurs naturally in the known universe. It is produced abundantly in the core of massive stars by the fusion of chromium and helium at extremely high temperatures. Each of these supergiant, iron-containing stars only lives for a brief while before violently blasting as a supernova, scattering iron into space and onto rocky planets like Earth. Iron is present in the Earth’s crust, core and mantle, where it makes up about 35 percent of the planet’s total mass.

Iron is crucial to the survival of all living organisms. Biological systems are exposed constantly to high concentrations of iron in igneous and sedimentary rocks. Microorganisms can uptake iron from the environment by secreting iron-chelating molecules called siderophores or via membrane-bound proteins that reduce Fe+3 (ferric iron) to a more soluble Fe+2 (ferrous iron) for intracellular transport. Plants also use sequestration and reduction mechanisms to acquire iron from the rhizosphere, whereas animals obtain iron from dietary sources.

Once inside cells, iron associates with carrier proteins and with iron-dependent enzymes. Carrier proteins called ferritins (present in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes) store, transport and safely release iron in areas of need, preventing excess free radicals generated by high-energy iron. Iron-dependent enzymes include bacterial nitrogenases, which contain iron-sulfur clusters that catalyze the reduction of nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) in a process called nitrogen fixation. This process is essential to life on Earth, because it’s required for all forms of life for the biosynthesis of nucleotides and amino acids.

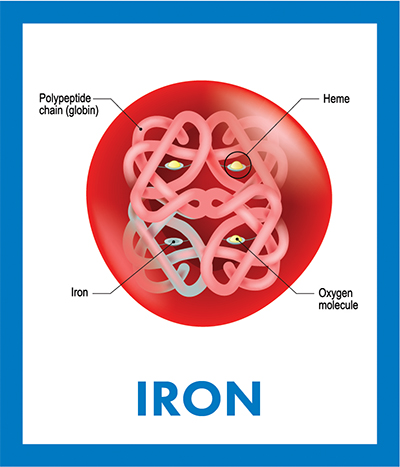

Some iron-binding proteins contain heme — a porphyrin ring coordinated with an iron ion. Heme proteins include cytochromes, catalase and hemoglobin. In cytochromes, iron acts as a single-electron shuttle facilitating oxidative phosphorylation and photosynthesis reactions for energy and nutrients. Catalase iron mediates the conversion of harmful hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water, protecting cells from oxidative damage. In vertebrates, the Fe+2 in hemoglobin is reversibly oxidized to Fe+3, allowing the binding, storage and transport of oxygen throughout the body until it is required for energy production by metabolic oxidation of glucose.

Living organisms have adapted to the abundance and availability of iron, incorporating it into biomolecules to perform metal-facilitated functions essential for life in all ecosystems.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.