For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

Every month in 2019 we are looking at one or more chemical elements essential for life in commemoration of the 150th anniversary of Mendeleev’s periodic table. For January and February, we selected hydrogen and iron, respectively, and described their function in biochemical reactions involving electron transport.

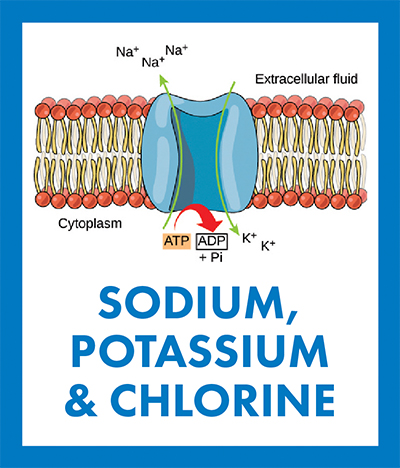

The Na+/K+ pump uses energy from the breakdown of adenosine triphosphate into adenosine diphosphate and inorganic phosphate to move 3 Na ions out to the extracellular space and 2 K ions into the cytoplasm, creating a charge imbalance across the cellular membrane. CNX OpenStax/Wikimedia Commons

The Na+/K+ pump uses energy from the breakdown of adenosine triphosphate into adenosine diphosphate and inorganic phosphate to move 3 Na ions out to the extracellular space and 2 K ions into the cytoplasm, creating a charge imbalance across the cellular membrane. CNX OpenStax/Wikimedia Commons

March is National Kidney Month, so we are highlighting three elements central to renal function: sodium, or Na; potassium, or K; and chlorine, or Cl.

Sodium and potassium, atomic numbers 11 and 19, respectively, are highly reactive metals with similar chemical properties, both listed in group 1, the alkali metals, of the periodic table. Both have a single valence electron in their outer shell, which they readily donate, creating positive ions, or Na+ and K+ cations. Chlorine, a gas at room temperature with atomic number 17, is a highly reactive element with an affinity for electrons. As a strong oxidizing agent, chlorine is abundant as chloride anions, or Cl-, that combine with Na+, K+ and other cations to form chloride salts.

Sodium is the seventh most abundant element on Earth, and potassium is the 17th. They exist in rock-forming minerals such as salt and granite. Chlorine is the 21st most abundant element in the Earth’s crust, occurring exclusively as ionic chloride compounds. Sodium and chlorine, constantly leached by water from mineral salts, are the most abundant elements dissolved in the oceans.

Sodium and potassium ions are crucial for most cells. Microorganisms use transmembrane ion pumps, such as the Na+/H+ antiporter or Na+ translocation systems coupled to metabolic reactions, to move Na+ ions against their concentration gradient, generating electrochemical energy to drive solute transport or to move flagellar motors (in bacteria) and to produce reducing power for biochemical reactions. K+ is the main monovalent cation in prokaryotes; it is essential to maintain intracellular pH, to generate energy via electrochemical gradients and to sustain turgor pressure.

In animals, the Na+/K+ ion pump pushes sodium and potassium across the cell membrane in opposite directions, maintaining a low Na+ concentration and a high K+ concentration inside the cell. This ionic imbalance between the cytosol and the extracellular medium creates a transmembrane potential — or voltage difference — essential to conducting electrical signals in excitable neurons and myocytes. A similar ion transporter moves H+ and K+ ions across the membrane of parietal cells, helping mammals acidify stomach contents and digest food.

Chloride ions are also necessary for all known life. Some prokaryotes use chloride compounds as a carbon and energy source and chlorine ions as terminal electron acceptors during anaerobic growth. In most cells at rest, the concentration of Cl- is lower in the cytosol than in the extracellular fluid via activity of gated ion channels that contribute to the polarization of cellular membranes. In animals, parietal cells in the stomach secrete Cl- ions to produce hydrochloric acid required for food breakdown. In humans, the defective protein in the disease cystic fibrosis is an ion channel specific for Cl- whose impaired activity results in less bactericidal activity — and more infections — in the lungs.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Fasting, fat and the molecular switches that keep us alive

Nutritional biochemist and JLR AE Sander Kersten has spent decades uncovering how the body adapts to fasting. His discoveries on lipid metabolism and gene regulation reveal how our ancient survival mechanisms may hold keys to modern metabolic health.

Redefining excellence to drive equity and innovation

Donita Brady will receive the ASBMB Ruth Kirschstein Award for Maximizing Access in Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Mining microbes for rare earth solutions

Joseph Cotruvo, Jr., will receive the ASBMB Mildred Cohn Young Investigator Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.