Can membrane stress protect mycobacteria?

Every now and then, what seems like a minor observation leads to a multiyear journey.

Yasu Morita’s lab at the University of Massachusetts Amherst studies the pathogenesis of mycobacteria, a genus that includes tuberculosis- and leprosy-causing species. Specifically, they study the multilayered plasma membrane and cell wall system that protect these bacteria — from antiseptic cleaning agents, for instance.

While working on an unrelated project, lab members noticed that membrane fluidization led two membrane glycolipids (lipids with a carbohydrate attached via glycosidic bond) called phosphatidylinositol mannosides, or PIMs, to undergo acylation. The two triacylated PIMs were transformed into their tetra-acylated forms.

The lab’s study exploring the conditions for and effects of this acylation recently was published in the Journal of Lipid Research. Peter Nguyen, an undergraduate researcher in the Morita lab, was first author on the paper. “We wanted to study this phenomenon, this physiological response to a membrane fluidizing, because we thought it might be significant to how mycobacterial cells can respond to certain stresses, like environmental threats,” he said.

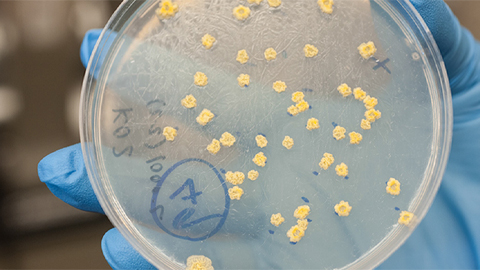

Early on, the lab decided to take a systematic approach. Early experiments showed that PIMs are the only major class of bacterial lipids affected by benzyl alcohol, a membrane fluidizer, and that the effect is a biological response (as opposed to an experimental artifact). The scientists also tested other types of membrane stressors, ultimately finding that only membrane fluidizers caused the full acylation effect.

This particular result came about halfway through the experimental process, which was a relief, Nguyen said. “If there was anything (else) being thrown at it that caused acylation, it would have been a much different story.”

One surprising result came when the scientists examined the reaction kinetics of acylation. As with all the experiments, they used high-performance thin-layer chromatography to visualize the presence of each PIM qualitatively and a mannose standard curve to find relative quantities. A time course experiment showed that the conversion of triacylated to tetra-acylated PIMs took just 20 minutes — one of the fastest cases of mass lipid conversions seen to date. Most mass conversions of mature lipids take several hours, so this reaction’s speed indicates an enzymatic mechanism independent of protein synthesis.

The researchers don’t know what this enzyme is, but Nguyen said, “It seems to play a significant role in what’s happening in response to environmental threats.”

They have shown that rapid PIM acylation is conserved among mycobacteria including the tuberculosis pathogen. Now, they need to identify the acyltransferase to understand better how these cells respond to stress, he added. “A lot of the membrane synthesis in mycobacteria is not well (understood), which is a big issue because tuberculosis is still a huge public health threat.”

The researchers also looked at some practical implications of PIM acylation by testing the response of Mycobacterium smegmatis, a nonpathogenic cousin of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, to antiseptic detergents benzethonium chloride and sodium dodecyl sulfate, or BTC and SDS, with and without a membrane fluidizing pretreatment. While the SDS sensitivity was unaffected by benzyl alcohol fluidization, the pretreated cells were far more resistant to BTC than their untreated counterparts.

The team hypothesizes that increased PIM acylation strengthens the membrane and thus the bacteria’s defenses. While it’s not great news for humans trying to avoid life-threatening diseases, the results bring researchers one step closer to understanding how mycobacteria membranes work and, by extension, how we can counter them.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.