From the journals: JLR

Determining how lipid pathways and cardiovascular disease are linked is a complex and rapidly evolving quest. Read about recent findings published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

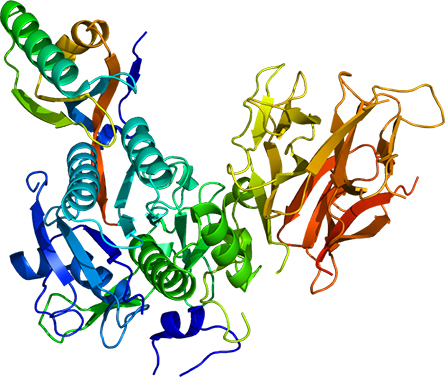

Furin as a metabolic deactivator of PCSK9

The enzyme proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, or PCSK9, regulates cholesterol metabolism by binding and chaperoning the low-density lipoprotein, or LDL, receptor to be degraded. That receptor clears LDL from circulation, making PCSK9 an appealing drug target: Blocking PCSK9 lowers blood LDL concentration, thereby reducing risk for cardiovascular disease.

PCSK9 has two known active forms: a mature form and a less understood furin-cleaved form, PCSK9_55. Carlota Oleaga and colleagues at the Oregon Health & Science University recently published the results of their studies to characterize this less known form in the Journal of Lipid Research.

First, Oleaga's team transfected a line of human embryonic kidney cells with the mature form of PCSK9 and furin vectors to test where PCSK9_55 was formed. As expected, the mature form was furin-cleaved to form PCSK9_55, with greater amounts of PCSK9_55 found in the extracellular space and only moderate amounts within cells. Adding a furin inhibitor that could cross the cell membrane decreased this extracellular formation.

The researchers engineered the embryonic kidney cells to express a recombinant PCSK9_55. Lacking a prodomain sequence that is essential to PCSK9 secretion, this form's abundant intracellular expression and retention were unsurprising. However, no change in secretion was detected when the recombinant PCSK9_55 was expressed with a prodomain or a prodomain donor. These results suggest that PCSK9_55 is not secreted into the extracellular space because it is markedly altered from the uncleaved parent.

Oleaga and colleagues propose that furin could act as a metabolic deactivator of PCSK9. Furin post-translationally modifies extracellular PCSK9 to form PCSK9_55, which has reduced capacity for LDL receptor degradation. When PCSK9_55 reenters the cell, it cannot be secreted back into circulation and eventually is catabolized. Further testing of this model could provide insight into drug development and treatments for cardiovascular disease.

Expressing CETP slows endotoxin clearance in mice

When Gram-negative bacteria enter the bloodstream, they release lipopolysaccharides, or LPSs, which activate the innate immune system. LPSs are not metabolized in the body and must be disaggregated and excreted in bile through a pathway known as the reverse LPS transport, or RLT, pathway. Increasing our knowledge of the RLT pathway could help with detection and treatment of sepsis, a life-threatening inflammatory immune response to infection that affects over 1.7 million adults in America each year.

Aloïs Dusuel and colleagues at the University of Burgundy recently published findings in the Journal of Lipid Research that a protein tightly related to key players of the RLT pathway, cholesteryl ester transfer protein, or CETP, does not contribute to the binding and transfer of LPS in plasma. However, when the researchers injected purified LPS into mice to simulate infection, the mice that were genetically altered to express CETP cleared endotoxins at a slower rate than mice who expressed no CETP. The CETP-expressing mice also had worse sepsis outcomes. The researchers suggest looking into the inflammatory response over time to better understand the role CETP plays in the inflammatory process and, possibly, in sepsis.

A look at atherosclerotic lesions in diabetes

Atherosclerosis is a progressive condition that increases risk of heart disease. Jenny Kanter and Karin Bornfeldt of the University of Washington School of Medicine have shown previously that the low insulin levels characteristic of diabetes lead to increased levels of apolipoprotein C3, or APOC3, and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, or TRLs, as well as accelerated atherosclerosis.

Kanter and Bornfeldt recently published fluorescence microscopy images of atherosclerotic lesions in a mouse with induced Type 1 diabetes in the Journal of Lipid Research. Their experiment focuses on two apolipoproteins: APOB, which is the primary apolipoprotein of low-density lipoprotein, very low-density lipoprotein, chylomicrons and remnant lipoproteins; and APOC3, which slows the clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnant lipoprotein particles, or RLPs, lipids that have been linked previously to cardiovascular disease.

The researchers found that APOC3 and APOB colocalize in atherosclerotic lesions of the aorta, supporting their hypothesis that the lipoproteins containing APOC3 particles could be these TRLs and RLPs. Their images also show that APOC3 and APOB are localized near lesional macrophages. Accumulation of these TRLs and RLPs can lead to increased accumulation of lesional macrophages, thereby worsening atherosclerosis and increasing cardiovascular disease risk.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.