A simple method to determine phase preference of proteins on live cell membranes

Scientists at National University of Singapore have demonstrated a simple and fast method to determine if a biomolecule partitions into lipid domains on live cell membranes. Their work was published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

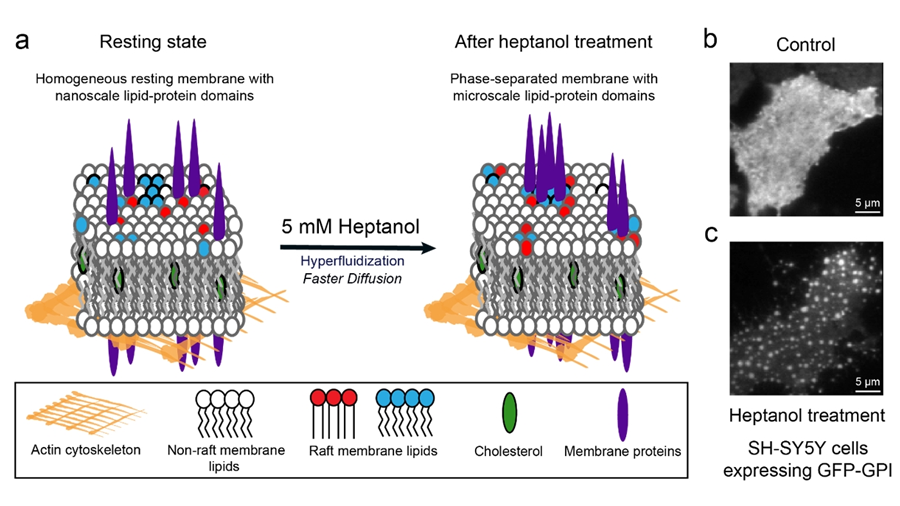

Cellular membranes are dynamic assemblies of lipids and proteins with some components organized as domains. Proper cell function requires the partitioning of lipids and proteins into these domains, which are often rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids. However, they are too small (10-200 nm in size) and dynamic (possibly only tens of milliseconds in lifetime) to be observed even with modern super-resolution microscopy techniques.

Traditional methods to determine domain localization involve biochemical assays that require many cells, are prone to artifacts as they are conducted in vitro, and are slow. Although fluorescence-based techniques can probe these domains in live cells, they require specialized instrumentation and are often difficult to interpret.

The research team at NUS developed a simple fluidizer-based method to determine if a molecule prefers to partition into lipid domains on cell membranes.

The team added heptanol to live cells and showed that within 15 minutes it induces clustering of the nanometer-size lipid domains into larger micrometer-size domains that are easily detectable by standard fluorescence microscopes. The method works with both molecules that are genetically labelled with fluorescent proteins and those labelled using extrinsic labels, for example, antibodies.

The work was conducted in the lab of Thorsten Wohland and led by first author Anjali Gupta, who is now a research fellow at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital.

Gupta explained the significance of studying phase preference of molecules in membranes.

"Phase preference of molecules in membranes is fundamentally crucial for the essential biological processes originating at membranes, such as T-cell activation, a critical step during an immune response," she said. "Knowledge of the phase preference of molecules will support therapeutic development based on the modulation of lipid domains."

Wohland said: “The phase preference of molecules used to be difficult and time-consuming to establish. This new method, detected by chance, provides results in at most 15 minutes on live cells and can essentially be seen by eye in a simple microscope.”

The team hopes that this technique will enable a quick and facile identification of domain localization and will aid the wider research community.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.