Gut microbiome shaped by dietary sphingolipids

The gut microbiome comprises trillions of symbiotic micro-organisms that reside in our gastrointestinal tract and perform biochemical functions that affect metabolic health. Each individual’s microbiome is unique, and microbiome imbalance is associated with disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease.

Diet influences gut microbiome composition, and researchers have found that macronutrients such as carbohydrates, protein and fats are key mediators of this influence. Lipids are a major macronutrient, yet scientists know little about how individual classes of dietary lipids interact with the microbiome.

Elizabeth Johnson studies sphingolipids, a class of lipids that consist of a sphingoid backbone attached to a fatty acid via an amide bond. Sphingolipids not only are present in most foods and synthesized from scratch by the host tissue but also are produced by gut microbes themselves. This raises some questions: How do dietary sphingolipids interact with the micro-organisms that do and do not produce sphingolipids? Are they assimilated into the microbiome? If so, how do they influence microbial metabolism?

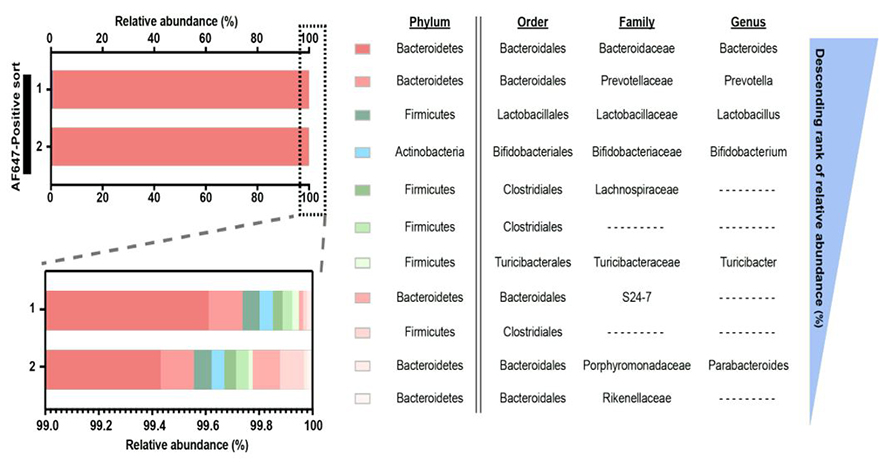

The Johnson lab developed a methodology called bio-orthogonal labeling-sort-seq-spec, or BOSSS, for identification and fate-mapping of dietary sphingolipids in the gut microbiome. Sphingolipids were synthesized with an alkyne tag, making them distinguishable from the body’s sphingolipids and those in the host microbiome. The researchers fed the tagged sphingolipids to mice and conjugated fluorescent dyes to the tagged metabolites using click chemistry. They used fluorescence-activated cell sorting to isolate microbes that took up the alkyne-tagged sphingolipid metabolites and those that did not and further identified them using 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

The team found that the dietary sphingolipids largely were taken up by Bacteroides and Prevotella spp., two key players in the human gut microbiome. Metabolomic analysis of the microbiome of the experimental mice revealed that non–sphingolipid-producing microbes such as Bifidobacterium, a major microbiome component, could process the sphingolipids in ways similar to the sphingolipid-producing microbes such as Bacteroides and also in unique ways.

Because the foods we eat are assimilated by our microbiomes, this work could have consequences for health and, more importantly, in development of the infant microbiome. Sphingolipids comprise approximately 0.2% to 1% of the total lipids in human milk. In breastfed infants, human milk and microbiome development are intimately related during the first six months of life. As the key interactors of dietary sphingolipids are also major components of a healthy microbiome, Johnson and her group hypothesize that sphingolipids in milk could influence positively the development of the infant microbiome.

Min-Ting, first author on the paper published in the Journal of Lipid Research, looks forward to following up on their recent findings.

“We will next investigate the molecular consequences of sphingolipid consumption in infants and in our mouse models,” she said. “Furthermore, we will be using our BOSSS methodology to investigate how other lipids, for instance cholesterol, can shape the microbiome.”

Johnson believes such work has implications for microbiome-related nutrition.

“We hope other researchers studying nutrition can apply our technique to their own research,” she said. “By determining how the microbiome might be interacting with different metabolites, we can ultimately use diet to positively influence our microbiome composition. This way we can really revolutionize the field of precision medicine.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.