Targeting the lipid envelope to control COVID-19

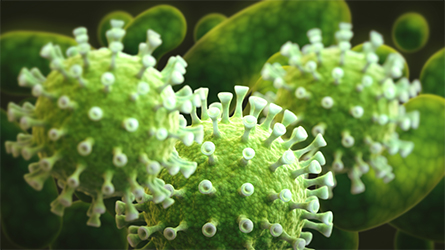

Viruses can be grouped into enveloped or nonenveloped. When enveloped viruses are shed by the host cell, they take part of the cell’s membrane and use it to surround themselves with a lipid envelope. Enveloped viruses include SARS-CoV-2, influenza and HIV. However, little research has been done on viral envelopes’ composition or how they could be used to target the virus directly.

disturb the lipid envelope of the SARS-CoV-2 molecule and affect the presence

of the virus in patients.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, governments around the world told people to wash their hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds or use hand sanitizer with at least 60% ethanol to minimize the virus’ spread; the idea was to dissolve the envelope. Valerie O’Donnell, a lipid biochemist and professor at Cardiff University, saw all this and asked one question: If soap can inactivate virus on our hands, could it do this in our throat?

“SARS-CoV-2 is being shed from the back of the throat, but no one is thinking about lipid membranes,” she said. When she began her research, “All the focus (was) on vaccines.”

In a recent Journal of Lipid Research publication, O’Donnell and a multidisciplinary team describe how they determined SARS-CoV-2’s lipid envelope composition and began testing how to use this information to target virus envelope degradation with existing commercial products, such as oral rinses.

If the virus has a membrane similar to a cell, SARS-CoV-2 should be sensitive to detergents; by targeting the envelope, the researchers could target the virus itself. The team first focused on the composition of the envelope to answer the question, Is the virus’ membrane similar to a cell membrane?

O’Donnell’s team found that the SARS-CoV-2 virus envelope consists mainly of phospholipids with some cholesterol and sphingolipids. Compared with cellular membranes, the SARS-CoV-2 envelope has higher levels of aminophospholipids on the outer surface. Exposed aminophospholipids are known to promote a pro-inflammatory environment, which might contribute to inflammation-related problems in COVID-19.

The composition of the SARS-CoV-2 envelope is such that it should be disrupted easily using soaps (surfactants). O’Donnell next proposed testing this by teaming up with dentists and virologists to determine if any oral rinse or mouthwash on the market could target and destroy these virus envelopes.

In collaboration with Richard Stanton and David Thomas at Cardiff University, the researchers tested various mouthwashes on patients hospitalized with COVID-19. They found that mouthwashes containing the antiseptic cetylpyridinium chloride eliminated the virus for at least one hour in about half the patients tested, whereas povidone-iodine and saline mouthwashes had little or no effect.

In the future, the team plans to study how the inflammatory mechanisms of the cells might affect the composition of the viral lipid envelope.

“Vaccines are not a complete solution,” O’Donnell said.

Preventive measures that target the virus in the throat or nasal passages have potential to combat COVID-19 transmission. Understanding the composition of SARS-CoV-2 lipid envelope membranes might provide new ways to target the virus and further elucidate how the virus interacts with host cells.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.