Did gonorrhea give us grandparents?

Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine previously found a set of human gene mutations that protect older adults against cognitive decline and dementia. In a new study, published July 9, 2022 in Molecular Biology and Evolution, they focus on one of these mutated genes and attempt to trace its evolution — when and why it appeared in the human genome. The findings suggest selective pressure from infectious pathogens like gonorrhea may have promoted the emergence of this gene variant in Homo sapiens, and inadvertently supported the existence of grandparents in human society.

variants that protect against dementia

The biology of most animal species is optimized for reproduction, often at the expense of future health and longer lifespans. In fact, humans are one of the only species known to live well past menopause. According to the “grandmother hypothesis,” this is because older women provide important support in raising human infants and children, who require more care than the young of other species. Scientists are now trying to understand what features of human biology make this longer-term health possible.

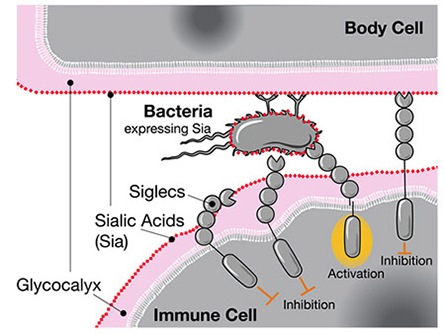

When researchers previously compared human and chimpanzee genomes, they found that humans have a unique version of the gene for CD33, a receptor expressed in immune cells. The standard CD33 receptor binds to a type of sugar called sialic acid that all human cells are coated with. When the immune cell senses the sialic acid via CD33, it recognizes the other cell as part of the body and does not attack it, preventing an autoimmune response.

The CD33 receptor is also expressed in brain immune cells called microglia, where it helps control neuroinflammation. However, microglia also have an important role in clearing away damaged brain cells and amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. By binding to the sialic acids on these cells and plaques, regular CD33 receptors actually suppress this important microglial function and increase the risk of dementia.

cell’s response, even if those acids are located on bacteria.

When Siglecs like CD33 sense human sialic acids, they inhibit the immune cell’s response, even if those acids are located on bacteria.

This is where the new gene variant comes in. Somewhere along the evolutionary line, humans picked up an additional mutated form of CD33 that is missing the sugar-binding site. The mutated receptor no longer reacts to sialic acids on damaged cells and plaques, allowing the microglia to break them down. Indeed, higher levels of this CD33 variant were independently found to be protective against late-onset Alzheimer’s.

In trying to understand when this gene variant first emerged, co-senior author Ajit Varki, MD, Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Cellular and Molecular Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and colleagues found evidence of strong positive selection, suggesting something was driving the gene to evolve more rapidly than expected. They also discovered that this particular version of CD33 was not present in the genomes of Neanderthals or Denisovans, our closest evolutionary relatives.

“For most genes that are different in humans and chimps, Neanderthals usually have the same version as the humans, so this was really surprising to us,” said Varki. “These findings suggest the wisdom and care of healthy grandparents may have been an important evolutionary advantage that we had over other ancient hominin species.”

Varki led the study with Pascal Gagneux, PhD, professor of pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and professor in the Department of Anthropology. The authors said the study provides new evidence supporting the grandmother hypothesis.

Still, evolutionary theory says reproductive success is the main driver of genetic selection, not post-reproductive cognitive health. So what was pushing the prevalence of this mutated form of CD33 in humans?

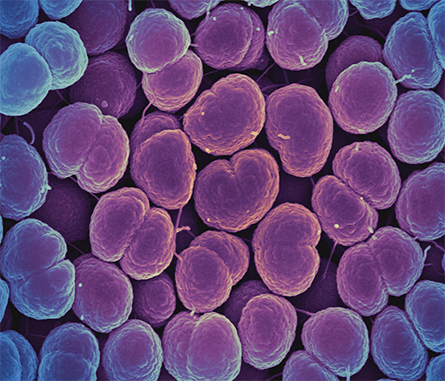

One possibility, suggest the authors, is that highly infectious diseases like gonorrhea, which can be detrimental to reproductive health, might have impacted human evolution. Gonorrhea bacteria coat themselves in the same sugars that CD33 receptors bind to. Like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, the bacteria are able to trick human immune cells to not identify them as outside invaders.

The researchers suggest that the mutated version of CD33 without a sugar-binding site emerged as a human adaptation against such “molecular mimicry” by gonorrhea and other pathogens. Indeed, they confirmed that one of the human-specific mutations was able to completely abolish the interaction between the bacteria and CD33, which would allow immune cells to attack the bacteria again.

Altogether, the authors believe humans initially inherited the mutated form of CD33 to protect against gonorrhea during reproductive age, and this gene variant was later co-opted by the brain for its benefits against dementia.

“It is possible that CD33 is one of many genes selected for their survival advantages against infectious pathogens early in life, but that are then secondarily selected for their protective effects against dementia and other aging-related diseases,” said Gagneux.

This article was produced by UC San Diego Health Sciences and originally appeared in the UC San Diego News Center.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.