Iron could be key to treating a global parasitic disease

Iron is a necessary nutrient to maintain bodily functions and healthy red blood cells. But the benefits of iron may extend further.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, researchers Sourav Banerjee and Rupak Datta showed that iron supplement can control symptoms of a global pathogenic disease, leishmaniasis, caused by the parasite Leishmania.

Leishmaniasis, found in tropical and subtropical countries, is spread by the bite of an infected female sandfly. Between 600 million and 1 billion people are at risk of infection, with an estimate of up to 1 million new cases occurring annually. It is among the top 10 neglected tropical diseases, mainly affecting people in poverty, and is connected to malnutrition, poor housing and a weakened immune system.

Depending on the Leishmania species causing the infection, symptoms and host immune response might vary — so understanding leishmaniasis is a complex problem. The high cost and toxicity of the drugs and the emergence of drug resistance in parasites limit the efficacy of current treatments.

Banerjee was a graduate student in Datta’s laboratory at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata during the study and is now a research associate at the University of Cambridge.

“While live-attenuated and adenovirus-based vaccines are currently under development, we are still far away from an end, as we do not know how efficiently these vaccine candidates would generate memory immune response,” Banerjee said. “Therefore, to better treat this disease, we need to have an in-depth knowledge of the pathogenesis of different types of leishmaniasis caused by the different Leishmania species.”

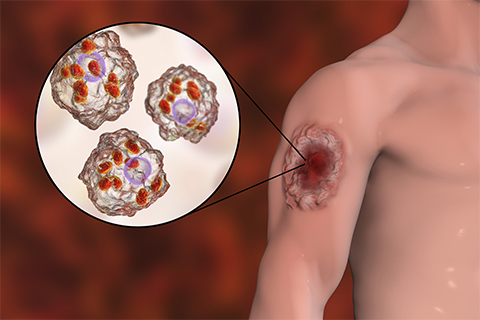

The study focused on the species Leishmania major, which typically replicates at the site of infection and causes cutaneous leishmaniasis, or CL. This common form of the disease causes skin ulceration and long-lasting scars.

Researchers know that Leishmania parasites need to hijack iron stores from the host to replicate and cause infection. However, they know little about how the infection changes our strict iron regulatory system. What are the consequences both at the site of infection and systemically?

To answer these questions, Banerjee and Datta infected mice with L. major in their footpads. With time, a lesion developed at the site of infection and showed increased iron accumulation. Further, the infection caused widespread changes in iron balance. It decreased hemoglobin levels, increased iron in the blood and caused spleen enlargement.

“We found that Leishmania major infection eventually leads to tissue damage and a significant depletion in liver iron reserves,” Banerjee said. “It is of great importance to know that in addition to causing a localized skin ulceration, Leishmania major infection has a far-reaching effect on internal organs and collectively can lead to anemic condition.”

To determine whether iron supplements can restore the depleted iron reserves and potentially restrict parasite infection, the researchers treated L. major-infected mice with oral iron. The parasite load decreased compared to untreated controls, and the iron supplement restored iron levels in the liver and serum.

“We show that oral iron supplementation at a minimal dose is highly effective in preventing the parasite infection in the experimental mouse model,” Banerjee said. “This highlights that nutritional immunity can play an essential role in battling Leishmania infection. This could be a cost-effective treatment regimen that is devoid of any painful interventions.”

Banerjee hopes parasitologists will continue investigating the molecular mechanisms behind the iron homeostasis perturbation upon L. major infection to determine whether the iron imbalance is mediated by the parasite or the host immune responses.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.