The science of staying strong

Roughly 560 million years ago, the first striated muscular system appeared in the cnidarian ancestor of jellyfish and corals. Haootia quadriformis, which lived anchored to the sea floor, likely used its new muscle fibers to grasp food, an upgrade from the passive filtering of its sponge phylum.

Since then, muscles have powered astonishing feats: the white-throated needletail flies 105 mph, lions drag prey twice their weight, and crocodiles crush with 5,000 pounds of bite force.

However, that power has a price. Every contraction wears muscle down, and with age, repair lags behind decay.

“The ethos of aging is that entropy wins,” Stuart Phillips, a professor of kinesiology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, said. “Eventually, the system just can’t hold its integrity because of mutations, oxidative damage, telomere shortening, you name it.”

Phillips has spent decades studying how skeletal muscle breaks down, regenerates and adapts, and how lifestyle, nutrition and molecular processes can slow that decline.

Scientists from other fields also contribute to the study of aging. By investigating how other animals use their muscles to work harder and longer than humans, evolutionary biologists determine what mechanisms to target for human muscle regeneration.

A broken leg and a new direction

In 1989, Phillips returned to McMaster for his senior year. A biochemistry major and rugby captain, he was ready for victory — until a broken leg benched him for months.

“I was devastated at the time,” Phillips said. “And then I took a senior thesis and spent time in the lab instead, and all of a sudden I fell in love with science.”

When his hip-to-ankle cast came off after 14 weeks, Phillips saw his leg had wasted away. His mentor explained how muscles rebuild, and Phillips was fascinated by their resilience. His undergraduate research turned into a doctoral project exploring protein intake and synthesis in athletes.

“For the first 15 years of my career, I was interested in what we could do in younger people,” Phillips said. “And then maybe research became ‘me-search’ as I got older.”

Today, his work focuses on slowing muscle loss in older adults. Drastic muscle reduction causes a condition known as sarcopenia, an age-related decline in muscle mass and function that reduces mobility, balance and independence.

The science and diagnosis of sarcopenia

Sarcopenia lacks clear genetic or biochemical markers, so clinicians rely on observation.

“You want to understand their baseline physical function,” William McDonald, a board-certified geriatrician, said. “Where were they six months ago and five years ago, and when they were younger?”

Muscle size and strength decrease naturally over time, but patients often experience accelerated decline after events such as infection, hospitalization, or immobility. McDonald said home visits are key for assessing real-world function — how patients climb stairs, carry groceries, or use walkers.

“There are research-level metrics like muscle circumference,” he said, “but they’re hard to apply in a realistic clinical setting.”

One practical test is the “get up and go” assessment, in which a patient rises from a chair without using their hands.

“Because (the patient) has to get up in a short period of time, it’s actually power that gets them out of a chair as opposed to strength,” Phillips said. “Quickness is the outward manifestation of power.”

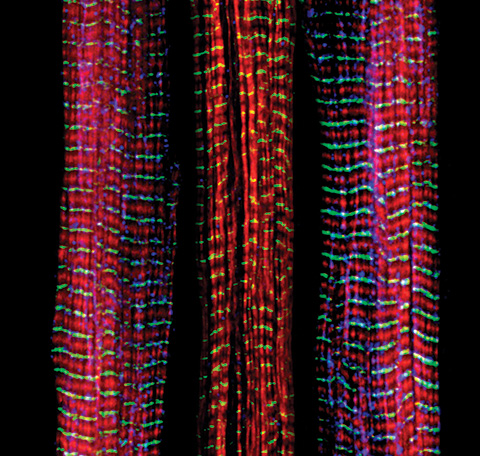

Molecular machinery of movement

Skeletal muscle is one of the body’s most metabolically active tissues, making up 30 to 40% of total mass and functioning under voluntary control. Its contraction relies on adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, the molecule that powers every twitch and flex.

During exercise, ATP stores are rapidly depleted and must be regenerated by mitochondria. This process also produces reactive oxygen species, or ROS, unstable molecules that play dual roles: supporting signaling and inflammation at normal levels but causing oxidative stress and DNA damage when overproduced.

To counteract ROS, cells deploy a complex antioxidant defense composed of enzymes and nonenzymatic antioxidants. As people age, however, mitochondrial efficiency declines. ATP production falls, ROS accumulation increases and antioxidant defenses weaken. This imbalance contributes to muscle atrophy, slow recovery and reduced exercise capacity in older adults.

Molecular clues from evolution

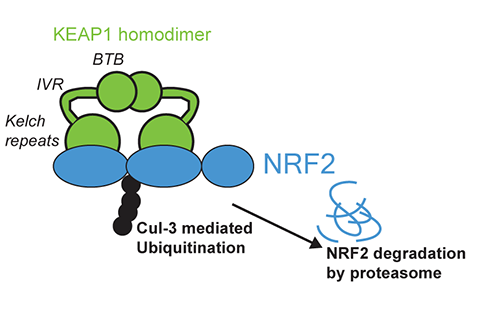

The biochemical roots of muscular aging may trace back through evolution. Two key regulators, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, or NRF2, and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1, or KEAP1, form a molecular switch that helps cells respond to oxidative stress.

At Vanderbilt University, Gianni Castiglione, an assistant professor of biological sciences, studies these proteins across species to understand how evolution fine-tuned muscle resilience.

In humans, NRF2 activity is tightly controlled by KEAP1, which contains cysteine residues sensitive to oxidation. Under normal conditions, KEAP1 binds NRF2 and sends it for degradation in the proteasome. When oxidative stress rises, KEAP1’s cysteines oxidize, altering its structure and releasing NRF2 to the nucleus, where it triggers antioxidant gene expression.

“Antioxidants are Goldilocks compounds,” Castiglione said. “Too much (antioxidant activity) is bad and can create reductive stress, which inhibits muscle signaling.”

How other animals endure extreme muscle use

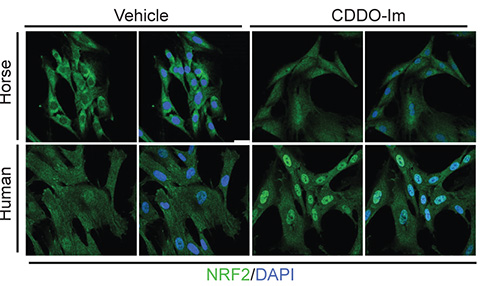

Horses, for instance, rely on sustained and powerful muscular output. Their muscles contain more mitochondria per centimeter cubed than humans, generating more ATP and more ROS. Yet. horses resist the oxidative damage that would debilitate humans.

Castiglione’s lab found that a single point mutation in KEAP1 lowers its ability to inhibit NRF2, leading to enhanced antioxidant production and better protection from oxidative stress.

“Whenever the cysteines get oxidized, it changes the conformation of KEAP1,” Castiglione said. “It doesn’t release NRF2, it just alters how it’s bound.”

This “hinge and latch” model allows one part of KEAP1 to unbind while the rest stays connected, keeping NRF2 partially engaged. As a result, newly produced NRF2 can accumulate in the nucleus and strengthen antioxidant defenses.

Birds show similar adaptations. “NRF2 mutations in humans can lead to cancer,” Castiglione said. “And yet birds have all of these mutations and they’re thriving — not despite them, but because of them.”

These comparative studies suggest that evolution has repurposed the same molecular machinery for vastly different ends: adaptation in animals versus disease in humans.

When adaptation turns harmful

In humans, overproduction of NRF2 can cause disease. Constant activation supports cancer cell survival, enabling tumors to handle high metabolic activity and ROS stress.

“The high metabolic activity of a cancer cell is analogous to the high metabolic activity of a horse or bird,” Castiglione said. “You get disease or adaptation depending on the context.”

NRF2 overactivity can also promote atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease marked by plaque buildup in arteries. Yet, despite the risks, controlled activation of NRF2 remains an attractive target for treating diseases caused by oxidative stress, from neurodegeneration to diabetes.

“A lot of (Food and Drug Administration)–approved drugs target NRF2 because for a lot of different diseases, a commonality is oxidative stress,” Castiglione said.

Preventing decline

Balancing oxidative stress begins with lifestyle. Both Phillips and McDonald emphasize that regular exercise and proper nutrition remain the most effective ways to preserve muscle health.

“Resistance training is king, and good nutrition is queen,” Phillips said. “Until we invent the anti-aging pill, we’re left with lifestyle choices.”

Sarcopenia is not inevitable. Resistance and strength training, combined with adequate protein and vitamin D intake, can slow muscle loss and preserve independence.

Evolutionary biology shows that species adjust ROS-regulating proteins based on their muscular demands, flying, sprinting or swimming. Humans cannot evolve that quickly, but exercise triggers epigenetic changes that enhance muscle function and antioxidant response even late in life.

No amount of exercise will increase a human’s lifespan. Instead, Phillips said, people should be focusing on increasing “healthspan.”

McDonald agrees: “We should be realistic but optimistic. It may not be running a marathon again but getting out of the house to have lunch with friends.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.