Toxoplasma gondii parasite uses unconventional method to make proteins for evasion of drug treatment

A study by Indiana University School of Medicine researchers sheds new light on how Toxoplasma gondii parasites make the proteins they need to enter a dormant stage that allows them to escape drug treatment. It was recently published with special distinction in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

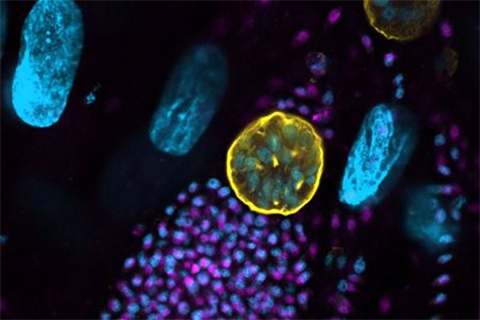

Toxoplasma gondii is a single-celled parasite that people catch from cat feces, unwashed produce or undercooked meat. The parasite has infected up to one-third of the world's population, and after causing mild illness, it persists by entering a dormant phase housed in cysts throughout the body, including the brain.

Toxoplasma cysts have been linked to behavior changes and neurological disorders like schizophrenia. They can also reactivate when the immune system is weakened, causing life-threatening organ damage. While drugs are available to put toxoplasmosis into remission, there is no way to clear the infection. A better understanding of how the parasite develops into cysts would help scientists find a cure.

Through years of collaborative work, IU School of Medicine professors Bill Sullivan, and Ronald C. Wek, have shown that Toxoplasma forms cysts by altering which proteins are made. Proteins govern the fate of cells and are encoded by mRNAs.

"But mRNAs can be present in cells without being made into protein," Sullivan said. "We've shown that Toxoplasma switches which mRNAs are made into protein when converting into cysts."

Lead author Vishakha Dey, a postdoctoral fellow at the IU School of Medicine and a member of the Sullivan lab, examined the so-called leader sequences of genes named BFD1 and BFD2, both of which are necessary for Toxoplasma to form cysts.

"mRNAs not only encode for protein, but they begin with a leader sequence that contains information on when that mRNA should be made into protein," Dey said.

All mRNAs have a structure called a cap at the beginning of their leader sequence. Ribosomes, which convert mRNA into protein, bind to the cap and scan the leader until it finds the right code to begin making the protein.

"What we found was that, during cyst formation, BFD2 is made into protein after ribosomes bind the cap and scan the leader, as expected," Dey said. "But BFD1 does not follow that convention. Its production does not rely on the mRNA cap like most other mRNAs."

The team further showed that BFD1 is made into protein only after BFD2 binds specific sites in the BFD1 mRNA leader sequence.

Sullivan said this is a phenomenon called cap-independent translation, which is more commonly seen in viruses.

"Finding it in a microbe that has cellular anatomy like our own was surprising," Sullivan said. "It speaks to how old this system of protein production is in cellular evolution. We're also excited because the players involved do not exist in human cells, which makes them good potential drug targets."

The Journal of Biological Chemistry featured the new study as an Editor's Pick, which represent a select group of the journal’s publications judged to be of exceptionally high quality and broad general interest to their readership.

This article is republished from the Indiana University School of Medicine Newsroom. Read the original here.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.