How tumor hypoxia suppresses the immune response

A team of researchers at the New England Inflammation and Tissue Protection Institute at Northeastern University have made headway in determining how the upregulation of adenosine in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment influences cell responses to immunotherapy.

Cells constantly are regulating every aspect of cell growth with complex signaling pathways and checkpoints to ensure everything is working normally. When cells notice something foreign or harmful, such as cancer cells, they activate their immune response to eliminate the harm. Cancer, however, has adapted to override this response, which allows cancer cells to grow into lethal tumors.

Kai Beattie is an undergraduate working under the direction of Michail Sitkovsky and Stephen Hatfield at the New England Inflammation and Tissue Protection Institute.

Beattie and colleagues are working to elucidate evolutionary conserved mechanisms of immune evasion and metastatic dissemination exploited by cancerous cells. He will discuss his team’s findings today during a poster presentation at the 2022 American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Annual Meeting held in conjunction with the Experimental Biology conference in Philadelphia.

“Studying cancer’s molecular underpinnings is especially intriguing to me because it represents an impossibly difficult biological puzzle that is the ultimate product of Darwinian evolution,” Beattie said. “When we study biochemical pathways enriched in tumors, we are actually beginning to understand ancient mechanisms of survival. Such is the case for hypoxia–adenosinergic signaling and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition.”

Cancer cells override the immune response by changing their surroundings to make the ideal environment for tumor growth.

Tumor hypoxia is when cancer cells have low oxygen levels because they are consuming oxygen to grow faster than the body can make more oxygen. Just as when we work out, we breathe faster to get more oxygen, when cells grow faster, they need more oxygen.

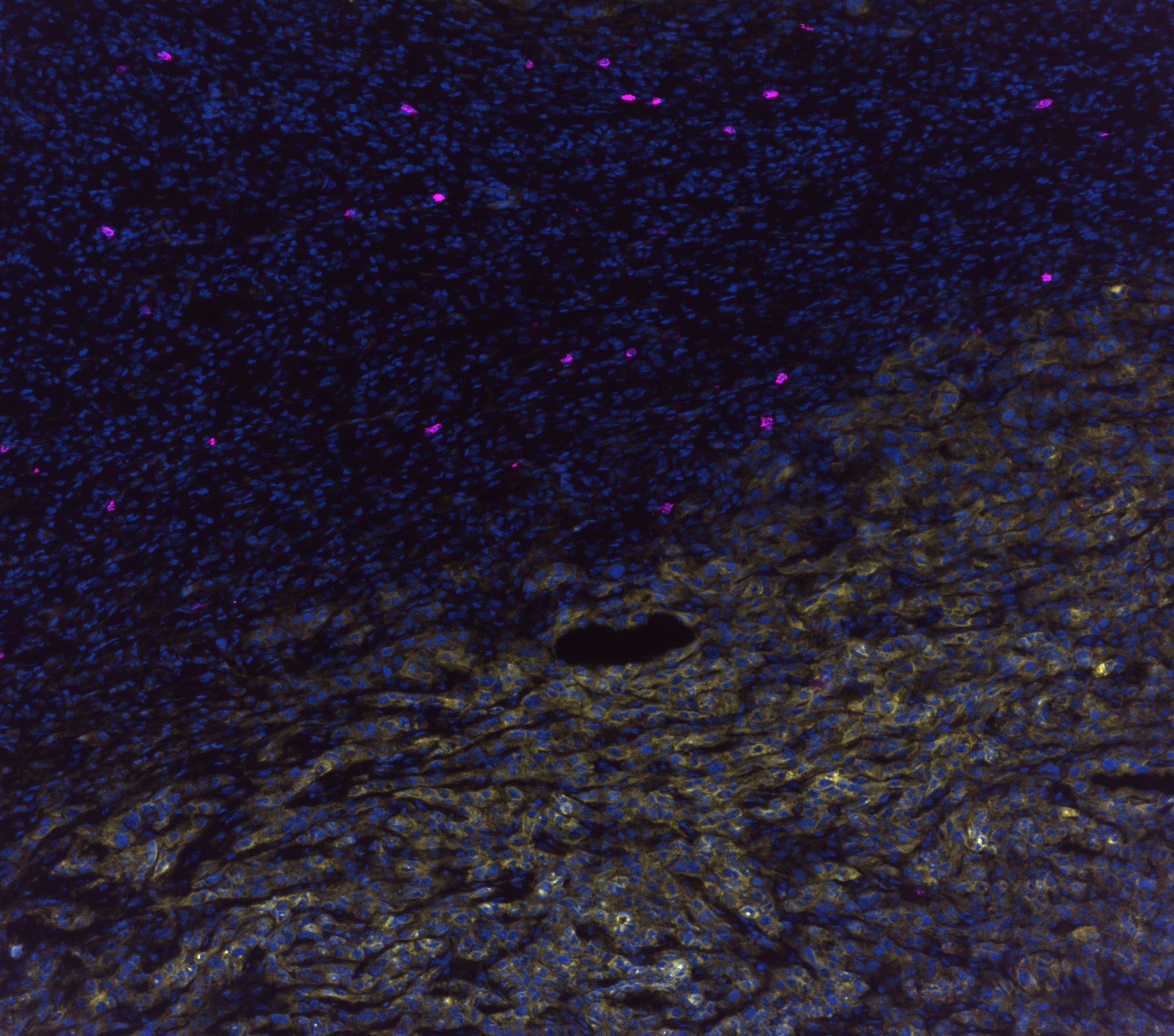

Tumor hypoxia upregulates the body’s hypoxic response, including increasing the amount of hypoxia-inducible factor 1, or HIF-1, alpha, which in turn produces extracellular adenosine. These increased levels of adenosine bind to adenosine A2A receptors, called A2AR for short, and suppress the body’s anti-tumor immune response, allowing the cancer cells to continue to grow without the immune response getting in the way.

Beattie and colleagues are studying the A2AR signaling pathway and how this pathway could be harnessed to enable antitumor responses. Beattie’s research specifically focuses on understanding the mechanism with which HIF-1ɑ increases adenosine levels. Better understanding the link between HIF-1ɑ and adenosine levels will add another potential regulation mechanism for programming the anti-tumor response.

While studying HIF-1ɑ’s mechanism, Beattie discovered adenosine-generating enzymes and changes in adenosine metabolism when hypoxic conditions are induced. Using epithelial murine breast cancer and quasi-mesenchymal carcinoma cells, he and his team found a remarkable difference in adenosinergic enzymes and epithelial–mesenchymal transition transcription factors during hypoxia.

Future work by Beattie and colleagues will focus on validating his findings in 3D cell aggregates that can mimic tissues (spheroids) and in preclinical mouse models, potentially using gene editing methods to establish key proteins involved in anti-hypoxia-HIF-1ɑ-A2AR treatment.

Beattie said the take-home message of his work so far is this: “Hypoxia-dependent signaling within neoplastic contexts represents one of many pathophysiological hallmarks of cancer that are integral to carcinogenesis and development of therapeutic resistance. Our knowledge of these biological capabilities is directly translatable to the development of treatments that, in the case of hypoxia–adenosinergic signaling, enhance anticancer immunity through the liberation of tumor-reactive cytotoxic lymphocytes from immunosuppression.”

Beattie continues to volunteer at the New England Inflammation and Tissue Protection Institute and has begun research at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. He plans to continue exploring cancer biology in preparation to apply for Ph.D. programs with an emphasis on genetics and functional genomics approaches.Kai Beattie will present this research between 12:45 and 2 p.m. Sunday, April 3, in Exhibit/Poster Hall A–B, Pennsylvania Convention Center (Poster Board Number A346) (abstract).

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.