New insights into how cells respond to altered gravity experienced in space

A new study has revealed insights into how cells sense and respond to the weightlessness experienced in space. The information could be useful for keeping astronauts healthy on future space missions.

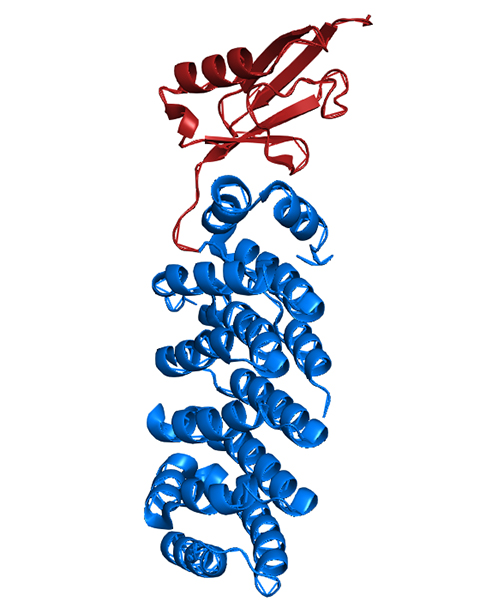

The gravity conditions in space, known as microgravity, trigger a unique set of cellular stress responses. In the new work, researchers found that the protein modifier SUMO plays a key role in cellular adaptation to simulated microgravity.

“Under normal gravity conditions, SUMO is known to respond to stress and to play a critical role in many cellular processes, including DNA damage repair, cytoskeleton regulation, cellular division and protein turnover,” said research team leader Rita Miller, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. “This is the first time that SUMO has been shown to have a role in the cell’s response to microgravity.”

Jeremy Sabo, a graduate student in Miller’s laboratory, will present the findings at Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, March 25–28 in Seattle.

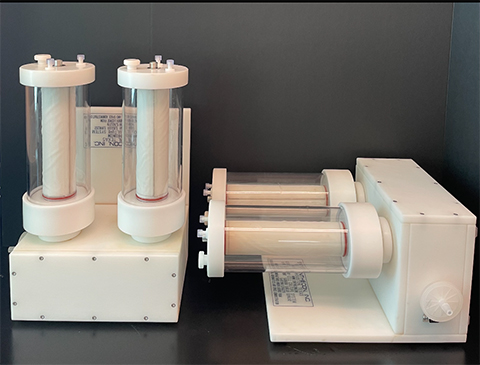

SUMO can interact with proteins via two types of chemical bonds: a covalent attachment to a target lysine or noncovalent interactions with a binding partner. The researchers looked at both types of interactions in yeast cells, a model organism commonly used to study cellular processes. They analyzed cells that had undergone six cellular divisions in either normal Earth gravity or microgravity simulated using a specialized cell culture vessel developed by NASA.

To understand which cellular processes were affected by the stress of microgravity, they began by comparing the levels of protein expression for cells that experienced each gravity condition. Then, to find out what was driving these protein changes, they looked more specifically at which of these proteins interacted with SUMO using mass spectroscopy.

In the cells experiencing microgravity, the researchers identified 37 proteins that physically interacted with SUMO and showed expression levels that differed from that of the Earth gravity cells by more than 50%. These 37 proteins included ones that are important for DNA damage repair, which is notable because radiation damage is a serious risk in space. Other proteins were involved in energy and protein production as well as maintaining cell shape, cell division and protein trafficking inside cells.

“Since SUMO can modify several transcription factors, our work may also lead to a better understanding of how it controls various signaling cascades in response to simulated microgravity,” said Miller.

Next, the researchers want to determine whether the absence of the SUMO modification on specific proteins is harmful to the cell when it is subjected to simulated microgravity.

Jeremy Sabo will present this research from 4–5:30 p.m. PDT on Tuesday, March 28, in Exhibit Hall 4AB of the Seattle Convention Center (Poster Board Number 330) (abstract). Contact the media team for more information or to obtain a free press pass to attend the meeting.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.