The music of proteins made audible

With the right computer program, proteins become pleasant music.

There are many surprising analogies between proteins, the basic building blocks of life, and musical notation. These analogies can be used not only to help advance research, but also to make the complexity of proteins accessible to the public.

We’re computational biologists who believe that hearing the sound of life at the molecular level could help inspire people to learn more about biology and the computational sciences. While creating music based on proteins isn’t new, different musical styles and composition algorithms had yet to be explored. So we led a team of high school students and other scholars to figure out how to create classical music from proteins.

The musical analogies of proteins

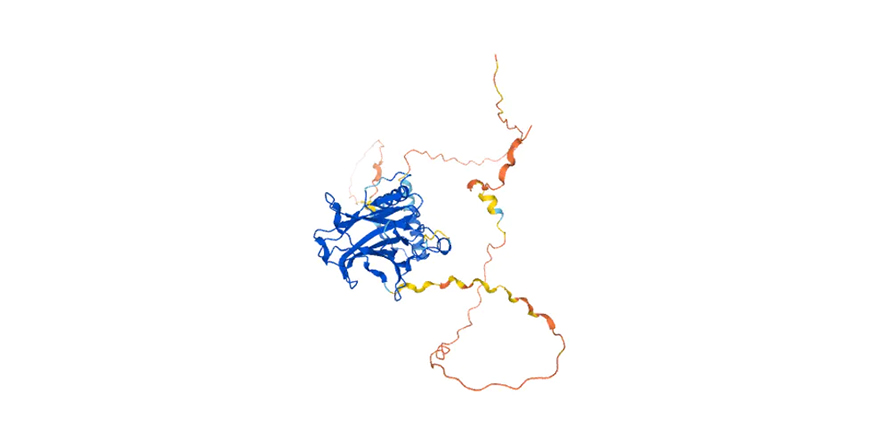

Proteins are structured like folded chains. These chains are composed of small units of 20 possible amino acids, each labeled by a letter of the alphabet.

A protein chain can be represented as a string of these alphabetic letters, very much like a string of music notes in alphabetical notation.

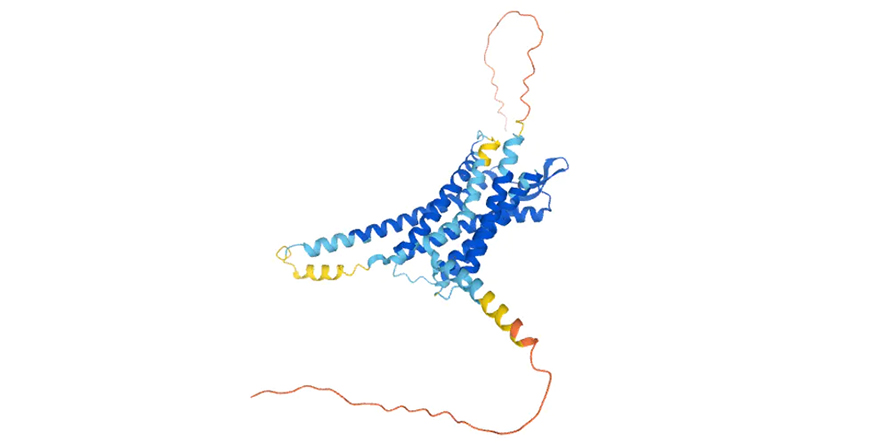

Protein chains can also fold into wavy and curved patterns with ups, downs, turns and loops. Likewise, music consists of sound waves of higher and lower pitches, with changing tempos and repeating motifs.

Protein-to-music algorithms can thus map the structural and physiochemical features of a string of amino acids onto the musical features of a string of notes.

Enhancing the musicality of protein mapping

Protein-to-music mapping can be fine-tuned by basing it on the features of a specific music style. This enhances musicality, or the melodiousness of the song, when converting amino acid properties, such as sequence patterns and variations, into analogous musical properties, like pitch, note lengths and chords.

For our study, we specifically selected 19th-century Romantic period classical piano music, which includes composers like Chopin and Schubert, as a guide because it typically spans a wide range of notes with more complex features such as chromaticism, like playing both white and black keys on a piano in order of pitch, and chords. Music from this period also tends to have lighter and more graceful and emotive melodies. Songs are usually homophonic, meaning they follow a central melody with accompaniment. These features allowed us to test out a greater range of notes in our protein-to-music mapping algorithm. In this case, we chose to analyze features of Chopin’s “Fantaisie-Impromptu” to guide our development of the program.

To test the algorithm, we applied it to 18 proteins that play a key role in various biological functions. Each amino acid in the protein is mapped to a particular note based on how frequently they appear in the protein, and other aspects of their biochemistry correspond with other aspects of the music. A larger-sized amino acid, for instance, would have a shorter note length, and vice versa.

The resulting music is complex, with notable variations in pitch, loudness and rhythm. Because the algorithm was completely based on the amino acid sequence and no two proteins share the same amino acid sequence, each protein will produce a distinct song. This also means that there are variations in musicality across the different pieces, and interesting patterns can emerge.

For example, music generated from the receptor protein that binds to the hormone and neurotransmitter oxytocin has some recurring motifs due to the repetition of certain small sequences of amino acids.

On the other hand, music generated from tumor antigen p53, a protein that prevents cancer formation, is highly chromatic, producing particularly fascinating phrases where the music sounds almost toccata-like, a style that often features fast and virtuoso technique.

By guiding analysis of amino acid properties through specific music styles, protein music can sound much more pleasant to the ear. This can be further developed and applied to a wider variety of music styles, including pop and jazz.

Protein music is an example of how combining the biological and computational sciences can produce beautiful works of art. Our hope is that this work will encourage researchers to compose protein music of different styles and inspire the public to learn about the basic building blocks of life.

This study was collaboratively developed with Nicole Tay, Fanxi Liu, Chaoxin Wang and Hui Zhang.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.