Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

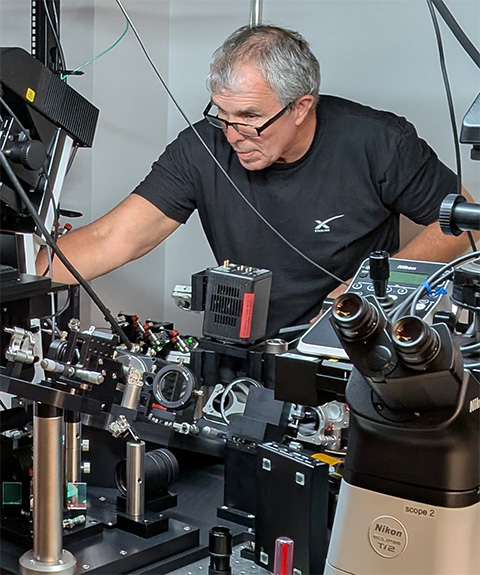

Scientists who come to Eric Betzig’s microscope facility to capture live 3D videos of living tissue often leave exhilarated. “Wow, this is amazing. I’ve seen things I’ve never seen before,” they tell him.

But about a week later, many call back, overwhelmed. “They have no idea what to do with 10 terabytes (of data) on a hard drive,” Betzig said.

It’s a limitation of human brains. “Unfortunately, from the savanna, we evolved to only understand two dimensions, or 2D, plus time,” Betzig said. Four-dimensional, or 4D, data combines three dimensions of space with time unfolding in a video, a scale and complexity the human brain is not built to analyze.

At the heart of Betzig’s work is a growing paradox in modern biology: scientists can now capture living systems in exquisite, 4D detail but lack the tools to interpret what they are seeing. As microscopes generate ever-larger datasets that track cells in space and time, the bottleneck is no longer imaging but understanding. Betzig is now focused on solving that problem, arguing that without new ways to analyze live 4D data, biology risks collecting stunning movies of life without learning its rules.

For Betzig, that challenge does not undermine the value of live, 4D imaging. It reinforces it. He believes studying life as it unfolds in space and time is the only way to truly understand biology, and that the analytical gap is a problem that can be solved.

“I have a religious conviction that life has to be studied live,” he said. He compared modern molecular biology techniques to trying to understand a car engine by tearing it apart and trying to put it back together, without ever watching how it functions in real life. “That's not going to work, folks.

However, people can already study cells live in 2D, and to Betzig, that’s not good enough. Flat, 2D systems strip away the spatial relationships cells rely on to move, communicate and function together, he said. In addition to studying exclusively live cells, he also believes cells must be studied in their natural environment, so videos of cells grown on flat coverslips are not sufficient.

To image cells in their natural habitat, Betzig developed microscopy techniques that provide 4D data of systems as large as an entire brain. This was a major advance for understanding how cells truly behave, revealing interactions that are invisible in simplified systems, but it also created a new challenge: humans cannot meaningfully interpret the sheer volume and complexity of the data.

After spending much of his career building microscopes, work that earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for contributions to super-resolution microscopy, Betzig is now turning his attention to the data those instruments produce. To him, solving the analysis problem is the next essential step.

Although he once described himself as “the last guy on earth who ever wanted to have anything to do with AI,” Betzig is now working to build an artificial intelligence model that can help humans interpret 4D data.

His goal is to build a model that can interpret 4D data, identify cell types, interactions and proteins, and respond to questions posed by scientists.

For example, a researcher might ask the model, “How do neutrophils squeeze through the mesenchymal space to reach their target?” and the AI would pull up videos of that happening. Then the user could ask follow-up questions, such as, “Tell me the speeds that the cells move through the passage,” which could be answered by the model providing the appropriate data, like a histogram.

However, no 4D AI model currently exists. “So, what we're asking for is something that is a little bit beyond the bleeding edge of what even the biggest and best in the AI field is doing right now,” Betzig said. The challenge lies in training models on massive datasets that lack standardized labels and span space, time and biology simultaneously. “So that’s a problem.”

But it is a problem Betzig believes is worth solving. Better ways to interpret live, complex data could reshape how scientists study development, disease and therapy response.

Beyond its importance for basic biology, Betzig also sees practical applications. He founded Eikon Therapeutics to use live imaging to track single molecules and reveal how drugs act inside cells, aiming to reduce failure rates in drug development.

Betzig will speak at the 2026 ASBMB annual meeting about the importance of live microscopy and the future of data analysis.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

In memoriam: Walter A. Shaw

He is the namesake for the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research and founded Avanti Polar Lipids.

Dorn named assistant professor

She will open her lab at the University of Vermont in fall 2026, and her research will focus on catalysis, synthetic methodology and medicinal chemistry.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.