Saving the bees with proteomics

You’ve probably heard about the bees dying. About a third of the world’s food depends on pollinators such as bees, wasps, ants and butterflies — and we are losing them.

back to the University of California, Riverside.

Boris Baer, professor for pollinator health at the Center for Integrated Bee Research at the University of California, Riverside, is an expert on this problem, and in a recent paper in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, he and his team describe how they have used proteomics creatively to help solve the pollinator crisis.

Many factors are hurting pollinators, including climate change, habitat loss and pesticide use. “We are losing all pollinators,” Baer said. “But in the case of the bees, we are aware of it because beekeepers record the losses.”

The U.S. has lost about two-thirds of its bee population since World War II; sometimes we resort to flying bees in from Australia or, as temperatures rise, even putting ice on top of hives so the wax doesn’t melt.

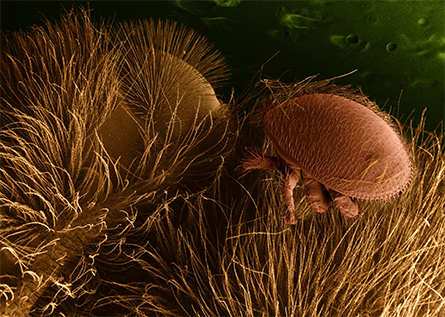

Among the many threats to pollinators is one specific to honeybees: the mite Varroa destructor, which has infested most of the world’s managed bee populations, weakening or killing whole colonies with the disease varroosis. And as if that weren’t bad enough, mites also can act as vectors for other diseases.

“It’s all doom and gloom. Why do we even continue to live on?” Baer said half-jokingly as he described this crisis. But he is, in fact, doing something about it.

In his recent paper, Baer, collaborating with researchers in Ethiopia and China, compared three types of bees: the European honeybee, which is susceptible to the mite and is the honeybee most common in the U.S., and the African and Eastern honeybees (from Ethiopia and China, respectively), which are naturally resistant to the mite.

The researchers used proteomics to study this naturally occurring resistance and to begin identifying what factors may protect bees. They hope that down the line, beekeepers can use this information to breed resistant bees.

Baer hypothesized that the immune response of resistant bees might be different from that of susceptible bees. “Bees have immune systems,” he said. “Bees can defend themselves. You just have to have the right bee.”

Using bees of all three types, the lab exposed half of each type to mites and then compared the proteomes in the hemolymph (bee blood), identifying almost 2,000 proteins. As they had hoped, they found variation between those they had exposed to the mites and those they had not. Crucially, they also found variation between the types of bees.

When the researchers sorted through the data, the two resistant bee genotypes showed an enrichment of proteins related to the immune system and detoxification. This supported the team’s hypothesis and could indicate that the resistant bees are mounting a stronger or different immune response to V. destructor, making it harder for the mites to take hold.

Baer’s lab is planning next to figure out what exactly these particular proteins do and possibly set up a breeding program informed by this data. They also hope to study the Africanized bee, a hybrid cross between the susceptible European bee and the protected African bee that also shows resistance.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.