Cows offer clues to treat human infertility

Infertility is a prevalent problem. Would-be parents struggling to conceive usually try in vitro fertilization, or IVF treatments, in which medical personnel remove an egg from an ovary, fertilize it with sperm in a laboratory and then place the fertilized egg, or blastocyst, in the uterus to grow and develop.

IVF has a low success rate, which physicians and researchers don’t completely understand. In many ways, the lab environment where the egg grows is often not optimal, leading to fewer viable blastocysts that can result in successful pregnancies. Patients often have to repeat the procedure multiple times before they conceive successfully.

The estrous cycle of cows is equivalent to the human menstrual cycle and is similar in structure and function. Cows also experience infertility, with a corresponding lack of knowledge regarding their estrous cycle. However, researchers can study cows more easily than humans, and if they solve infertility in cows, this could serve as a model for treating human infertility.

Researching cow infertility also benefits the dairy industry. Infertile cows are often sent to slaughterhouses, and farmers lose money.

Johanna Piibor, a veterinarian and researcher at the Estonian University of Life Sciences, has had a passion for cattle ever since she began studying veterinary medicine.

“I often observed the lack of diagnostic and prognostic protocols in treating cow infertility,” Piibor said, “and this motivated me to contribute to solving this issue by understanding the science of the estrous cycle.”

To help gain this understanding, Piibor and her colleagues decided to observe the changes in bovine uterine fluid extracellular vesicles, or UF-EVs, at different time points of the estrous cycle.

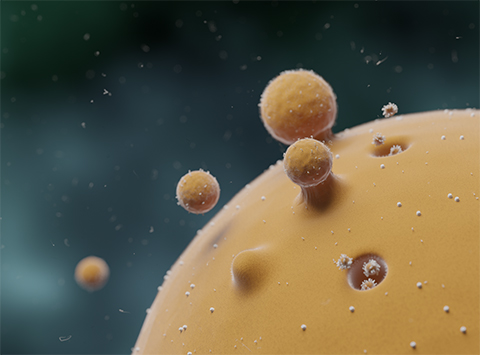

EVs are heterogeneous particles secreted by cells that carry biomolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids and metabolites and help cells communicate over long distances. The internal content of EVs changes depending on the health of the organism and can influence the response of the cells they deliver their messages to.

UF-EVs contain proteins that are essential in mechanisms of endometrial development. Piibor’s team wanted to see whether these EVs are also important for embryo development.

They took samples of uterine fluid from cows at different phases of the estrous cycle. These cows were synchronized with hormones to induce ovulation at the same time. The researchers isolated EVs from the uterine fluid and observed differences in EV content at each phase. They infused blastocysts in IVF cultures with EVs from different phases of the estrous cycle and observed their effect on the growth of blastocysts.

In a recent article in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, Piibor and colleagues reported that changes in the UF-EV proteome during the estrous cycle had an impact on blastocyst growth. EVs from the luteal phase of the cycle, when hormones that maintain pregnancy such as progesterone are highly concentrated, significantly increased the rate of blastocyst production. This shows that uterine fluid changes can affect IVF outcomes in cows — and provides clues to increase human IVF success rates.

Piibor’s next step is to compare UF-EVs from cows with clinical endometritis, a uterine inflammation, with those from healthy cows.

Piibor said EV research is a novel field and a challenging aspect is isolating the EVs from the fluid since there is still no agreed-upon isolation method and the technology is not sensitive enough to detect sufficient EVs.

“Optimizing the isolation protocol and developing ultrasensitive technology would allow significant leaps in the field,” she said, “and hopefully will save vast amounts of time in conducting EV research in the future.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.