Prion origins are key in study of chronic wasting disease

Chronic wasting disease, or CWD, is a contagious and fatal prion disorder that affects cervid species such as deer, elk, caribou, reindeer and moose. Cervids of all ages, captive and wild, can be affected.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that CWD is prominent in the continental U.S., Canada, Norway, Finland, Sweden and South Korea. Increased prevalence and spread of CWD endangers cervid populations in these regions. No vaccine or treatment exists.

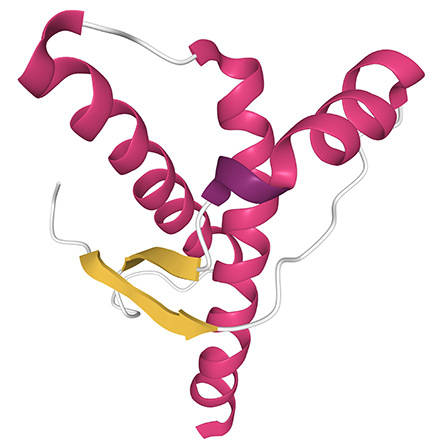

Like any prion disease, CWD is characterized by the misfolding of a normal protease-sensitive host protein, or PrPC, to a protease-resistant isoform, or PrPSc. The misfolded pathogenic PrPSc has distinct biochemical profiles that correlate with specific disease characteristics. CWD spreads when PrPSc is shed into the environment through urine, feces, bodily fluids or carcasses or by direct animal-to-animal contact.

Mark Zabel leads a team at Colorado State University that studies prion diseases.

“Chronic wasting disease can have serious consequences,” he said. “In Colorado and Wyoming, where the disease was first discovered, prevalence rates in specific herds are estimated to be between 30% and 50%. This rate in population decline can lead to local extinction of cervid species.”

Although CWD is a neurodegenerative disease, in cervids, PrPSc proteins are primarily of lymphogenic origin. Once PrPSc enters the body via oral or intranasal ingestion, it is replicated in the retropharyngeal lymph nodes, or LN. The PrPSc eventually accumulates in the obex, a region in the medulla of the central nervous system, or CNS, resulting in wasting and spongiform encephalopathy.

Typical of prion diseases, CWD is neurological, and the CNS has the highest prion concentration, so research has focused on brain-derived prions. However, the infectious prions shed in CWD primarily originate in the lymphoreticular system.

In a recent article in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Zabel’s team reports differences in the biochemical profiles of prion strains of lymphogenic and neurogenic origins in free-ranging white-tailed deer.

Zabel and his team report that paired obex and LN-derived prions from the same animal showed no significant differences in conformational stability, nor was interanimal variation within the same tissue substantial.

Glycoform ratio analysis showed differences in glycosylation patterns in prions derived from the obex and LN in the same animal. To the team’s surprise, LN-derived glycosylation patterns showed only marginal differences among animals, but brain-derived prions showed significant differences.

Using an ELISA-based structural profiling assay, the authors also saw greater conformational diversity in LN-derived prions than brain-derived prions.

“Prions that exist in infected animals are typically not a singular species but a sort of quasi-species or a cloud of different subspecies,” Zabel said. “We would argue that predominant species are selectedinside the animal from a large pool of diverse prions.”

Based on their observations, the authors propose that predominant isoforms of neurogenic PrPSc are selected by the brain from a larger pool of LN-derived PrPSc. The neurogenic prion strains selected can vary considerably from animal to animal.

Extraneural prion strains shed into the environment may have a lower species barrier than neurogenic prions. The ability to transmit infectious prions between species increases the zoonotic potential, or the ability to infect humans, of CWD. The study underscores the importance of including strain properties alongside prion positivity as a criterion for diagnostic tests used by wildlife management agencies.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Fasting, fat and the molecular switches that keep us alive

Nutritional biochemist and JLR AE Sander Kersten has spent decades uncovering how the body adapts to fasting. His discoveries on lipid metabolism and gene regulation reveal how our ancient survival mechanisms may hold keys to modern metabolic health.