Mapping fentanyl’s cellular footprint

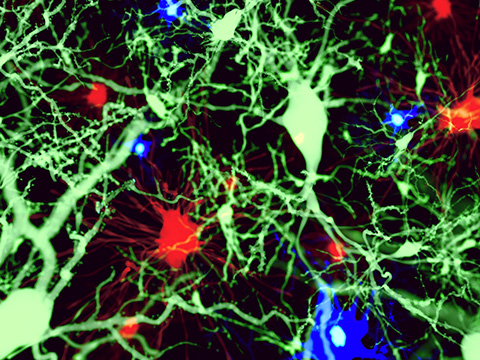

Emerging imaging tools are exposing ways fentanyl disrupts cells from within.

From its inception, fentanyl was designed for maximum potency. Synthesized as a painkiller, fentanyl’s high lipophilicity allows it to easily cross the blood-brain barrier, which quickens its analgesic effect, but also heightens its addictive potential.

In a recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research, scientists used a new imaging approach to map fentanyl’s effects on brain immune cells. Their findings could transform how addiction is assessed and lead to new diagnostic and therapeutic tools.

Supriya Mahajan, an associate professor of medicine at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and Rahul Das, a postdoc in Mahajan’s lab, wanted to take a closer look at how brain immune cells respond to a sudden influx of fentanyl. They joined forces with photonics experts and fellow UB professors Paras N. Prasad, Andrey Kuzmin and Artem Pliss to form a multidisciplinary team. Using an emerging spectroscopic technique called Ramanomics, the team captured this response at unprecedented resolution, down to the level of a single organelle.

“Because fentanyl is highly lipophilic, or fat-loving, it tends to accumulate inside lipophilic organelles, like lipid droplets, within these (immune) cells,” Das said.

The researchers wanted to follow fentanyl molecules into the lipid droplets and measure how the drug altered their composition.

“With the Ramanomics approach, we tried to understand how the composition of the lipid droplets is changing when the fentanyl enters,” Das said. “What are the chemical changes, the compositional changes, and the variations?”

Like Tupperware for fats, lipid droplets store lipids inside cells. But unlike containers, they are densely packed with lipids and active participants in cellular metabolism — regulating stress responses, inflammation and energy balance.

“The concentration and the chemical composition of these lipid droplets (reflect) the health of the cell,” Mahajan said.

Current research on lipid droplets is informing knowledge of the central nervous system and neurodegenerative diseases.

To observe fentanyl-induced changes in lipid droplets within astrocytes and microglia, two types of brain immune cells, the team used Raman microscopy to scan cultured cells with a laser beam. This approach revealed a cascade of subcellular changes triggered by high levels of fentanyl.

“Fentanyl builds up in the lipid droplets, and then it modifies the fats, proteins, RNA and sugars that are in that environment,” Mahajan said. “That contributes to how the brain’s protective system fails in those overdose conditions.”

The team found that fentanyl caused a loss of carbon-carbon double bonds in the phospholipid membranes of lipid droplets in both astrocytes and microglia, a sign of reduced unsaturation. Reduced unsaturation makes membranes more rigid and less fluid, disrupting permeability, protein function and signaling. Broadly, changes in phospholipid unsaturation in cell membranes are linked to a variety of neurological diseases.

They also detected changes in cholesterol, glycogen, phosphocholine and sphingomyelin levels. Many of these molecules are implicated in essential biochemical pathways, and certain changes in their concentrations can be linked to neuronal damage and cognitive decline.

This analysis is the first to reveal fentanyl’s behavior within lipid droplets in such molecular detail. The findings add to growing knowledge of addiction, neurodegeneration and inflammation — and may inform future therapeutic initiatives and treatments. “Now, we are trying to understand the chemistry,” said Das.

But in terms of Ramanomics, and of assembling these subcellular changes into a collection of addiction biomarkers, the researchers have their sights set on an even more ambitious goal: to identify susceptibility to and ultimately prevent addiction.

“Imagine that there are blood tests, scans that could detect small biochemical shifts (indicating addiction) before overdose symptoms set in,” Mahajan said. “That is our eventual dream, technology that will help people who are addicted.”

Das noted that there are wearable technological accessories that already track body metrics, like oxygen levels, noninvasively.

“Just imagine that kind of tech is applied to patients, or people who are given treatment, those who are nonaddicted and becoming addicted,” Das said. “Those gadgets could help inform doctors.”

The sensors that the team envisions could detect subtle biochemical changes that precede addiction or neurodegenerative symptoms.

Their work offers a glimpse into addiction’s smallest mechanisms and into a future where early detection could save lives.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.