JBC: Peptides to the rescue

Insulin and glucagon are well-known peptide hormones that keep our glucose levels within a healthy range. But they are only part of a complex network that controls concentrations of this ubiquitous sugar in blood and tissues. Other molecules regulate glucose by controlling insulin secretion from the pancreas or protecting pancreatic beta cells against stresses that lead to dysfunction or cell death.

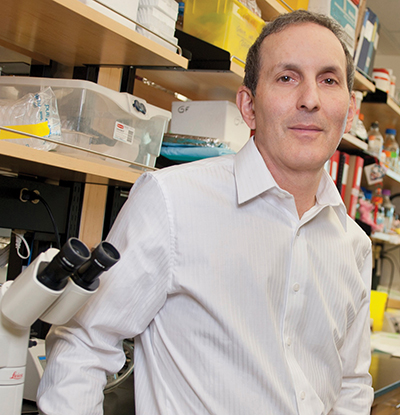

Daniel Drucker is the senior author on a seminal 2003 Journal of Biological Chemistry paper that showed that GLP-1R signaling protects beta cells from cell death.Lunenfeld–Tanenbaum Research Institute

Daniel Drucker is the senior author on a seminal 2003 Journal of Biological Chemistry paper that showed that GLP-1R signaling protects beta cells from cell death.Lunenfeld–Tanenbaum Research Institute

One of these protective regulators is glucagonlike peptide 1, or GLP-1. It’s 30 amino acids long and is produced in specialized epithelial cells of the intestine called L cells and also in the brain and other organs and tissues.

GLP-1 belongs to a group of peptides that mediate the incretin effect, an endocrine response to glucose arising from food digestion in the intestines. This response helps regulate food intake and the fate of dietary glucose. Specifically, GLP-1, which is released when food is ingested, binds to and activates the GLP-1 receptor, or GLP-1R, a G protein–coupled receptor on many cell types, including beta cells in which GLP-1R signaling stimulates insulin synthesis and secretion. The incretin effect stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells more strongly than exposure to glucose alone.

A 2003 article published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry added to our understanding of the incretin effect by showing that GLP-1R signaling protects beta cells from cell death. This is significant for preventing or managing type 2 diabetes, in which beta-cell apoptosis may contribute to insufficient pancreatic insulin production.

Yazhou Li and Daniel Drucker at Toronto General Hospital in Ontario, Canada, along with colleagues, exposed wild-type and GLP-1R–knockout mice to the compound streptozotocin, which induces beta-cell death, in the presence and absence of the specific GLP-1R agonist exendin-4. The authors then assessed the effect of the GLP-1R stimulation on glucose tolerance, blood and pancreatic insulin levels, and pancreatic cell viability and proliferation.

To find out what spurred this seminal paper and learn more about its findings, JBC reached out to Drucker, now at the Lunenfeld–Tanenbaum Research Institute, Mt. Sinai Hospital, in Toronto.

What prompted your investigation? In particular, what was unknown about GLP-1 and GLP-1R and their effects on beta-cell viability, and what motivated you to study these questions?

GLP-1 had previously been shown to expand beta-cell mass by stimulating beta-cell proliferation. We wondered whether GLP-1 might also contribute to the control of beta-cell mass by reducing cell death. We were also aware that cell survival pathways were activated by cAMP, an important downstream messenger that is increased by GLP-1R activation.

What were your main findings?

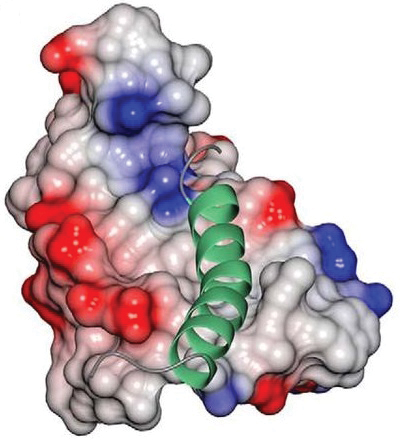

The small peptide GLP-1 (green ribbon) binds to and activates the GLP-1R (gray, red and blue structure) on beta cells and thereby protects them against injury and death.Swedberg et al./JBCWe made several interesting discoveries. First, pharmacological activation of the GLP-1R with exendin-4 reduced beta-cell death that had been produced by experimental pancreatic injury in mice. We noted that this reduction in beta-cell apoptosis is associated with preservation of beta-cell function and glucose homeostasis in the mice.

The small peptide GLP-1 (green ribbon) binds to and activates the GLP-1R (gray, red and blue structure) on beta cells and thereby protects them against injury and death.Swedberg et al./JBCWe made several interesting discoveries. First, pharmacological activation of the GLP-1R with exendin-4 reduced beta-cell death that had been produced by experimental pancreatic injury in mice. We noted that this reduction in beta-cell apoptosis is associated with preservation of beta-cell function and glucose homeostasis in the mice.

Second, we found that basal GLP-1R signaling is physiologically essential for beta-cell survival, as the GLP-1R knockout mice exhibited enhanced beta-cell injury when challenged with streptozotocin.

Third, we saw that GLP-1’s anti-apoptotic activities are direct, and we, that is, our collaborator Philippe Halban, could also demonstrate them ex vivo in purified rat beta cells exposed to cytotoxic cytokines, a model of tissue inflammation. We also discovered that GLP-1’s anti-apoptotic properties are not unique to beta cells and can be conferred to heterologous cells transfected with the gene encoding GLP-1R.

Why did you use exendin-4 rather than GLP-1 to stimulate GLP-1R?

We used exendin-4 because it’s a highly stable, degradation-resistant GLP-1R agonist that is more biologically potent in animals and humans than GLP-1. It was also the lead GLP-1R agonist in clinical trials and became the first GLP-1 drug approved for management of diabetes.

Does repeated exendin-4 stimulation downregulate the receptor as is sometimes the case with repeated receptor stimulation?

In most tissues, there is little evidence that continuous GLP-1R activation by agonists downregulates this receptor. This fortuitous finding enables the development of long-acting GLP-1R agonists for managing diabetes and obesity.

As your JBC paper has shown, the GLP-1R stimulation prevents beta-cell apoptosis and increases pancreatic islet mass. Could this increase heighten the risk for uncontrolled cell growth/cancer?

This has always been a theoretical concern, but there’s no evidence that would support it. The first GLP-1R agonist (exenatide, the common drug name for exendin-4, used in diabetes management) was approved for clinical use as an anti-diabetic medication in April 2005. After 14 years of clinical use, with multiple drugs and millions of patients taking the medication, we have not seen an increase in cancer rates due to exenatide or GLP-1R agonist use.

Is GLP-1 the major incretin hormone, or does it have some overlapping functions with other incretins, and do other incretin hormones also promote beta-cell mass?

Both GLP-1 and another peptide, gastric inhibitory polypeptide, or GIP, are important naturally occurring incretin hormones. GIP is likely the more important incretin under physiological conditions. And yes, most peptide ligands that, like GLP-1, increase cAMP levels in B cells — such as pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide, GIP, and fatty acids — also reduce beta-cell apoptosis.

Were your findings expected, and how has your own work and the field progressed since your paper’s publication?

Before our study, I don’t think anyone had clearly addressed the question of whether GLP-1R signaling can inhibit beta-cell death. Since our JBC publication, GLP-1R signaling has been shown to reduce cell death in many cell types, from beta cells to neurons to endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes.

As for the field, research into both the basic science and clinical relevance of GLP-1 has expanded tremendously since 2003. GLP-1R agonists are approved for treating patients with diabetes or obesity and under investigation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and neurological disorders. We continue to explore the mechanisms underlying GLP-1 action in numerous cells and tissues. In 2002, only 196 published studies of GLP-1 were listed in PubMed. In 2018 alone, there were 1,461, and the field continues to grow.

What was the impact of your paper on the field of diabetes and clinical research in general?

This is a little difficult to appreciate. The paper has been widely cited (author’s note: at this writing, it has been cited 712 times in Google Scholar), and it was one of the first studies to highlight a cytoprotective role and not just an insulin-secretory role for GLP-1.

It’s also noteworthy that GLP-1 has recently shown some promise in clinical trials investigating its therapeutic role in human neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and continues to be explored for therapeutic intervention in Alzheimer’s disease. So the concept that GLP-1 might generally protect vulnerable cells continues to have high clinical relevance.

Drucker and Li’s paper was nominated as a JBC Classic by JBC Associate Editor Eric Fearon at the University of Michigan Medical School. This article originally appeared in JBC. It has been edited for ASBMB Today. Click to read more JBC Classics.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.