Mapping out the protein path to hearing

When sound-induced vibrations are translated into electrochemical signals, humans and other animals can hear those sounds. Within the cochlea of the inner ear, inner hair cells, or IHCs, release neurotransmitter-filled vesicles at their synapse with afferent neurons, sending auditory information to the brain. Some researchers suspect a unique network of trafficking proteins and organelles is involved in this neurotransmission. However, scientists do not know the identities for most of these molecular players.

Previous studies reported a general protein profile of IHCs by analyzing whole cochleas. However, these studies did not identify the proteins found specifically in the IHC’s presynaptic regions, where vesicles are released.

Andreia Cepeda, who studied deafness during her Ph.D. at the University Medical Center Goettingen, wanted to uncover these details.

“One of the challenges has been the scarcity of material needed for these kinds of studies which require large amounts of purified sample,” Cepeda said. “Obtaining enough starting material from these IHCs is an extremely difficult and time-consuming task.”

To tackle this challenge, Cepeda teamed up with Momchil Ninov, who specializes in isolating synaptic vesicles, and others from the Max Planck Institute. The group developed a protocol that led to the first complete map of the IHC proteome, which they published in their recent article in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

Before identifying IHC proteins, the team had to isolate enough samples from mice for proteomic analysis, Cepeda’s most challenging task.

“I was the only one dissecting the cochleas,” she said, “and I had entire weeks where I was dissecting every day, all day simply to collect enough material.”

Cepeda and Ninov said they isolated roughly 150 organs of Corti per run, the receptor organs where the IHCs are located, from these cochleas — which further reduced the amount of sample they had to work with.

“Imagine how many cochleas (and how many mice) we need to obtain enough material to be used for further purification,” Ninov said. “To give you an idea, one starts with the cochlea of a mouse, which is about the size of a grain of rice, and under the microscope, we need to dissect (the organ of Corti), which is the size of a needle’s head.”

Though tedious, this step notably improved their sample purity for downstream analysis.

Following dissection and homogenization, the group separated the samples into subcellular fractions by differential centrifugation. Then they immunoisolated IHC-specific vesicles and organelles using an antibody against VGluT3, a glutamate transporter expressed exclusively in IHCs. This resulted in an enriched, albeit limited amount of material ready to be characterized by mass spectrometry. The group had access to a sophisticated mass spectrometer allowing them to identify proteins in very small amounts.

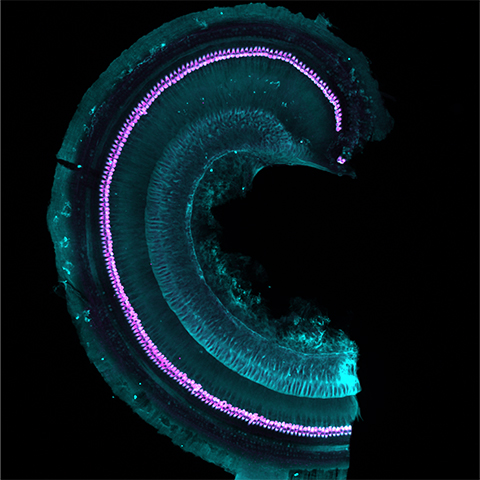

Using this workflow, the team introduced the first exhaustive list of proteins involved in vesicle trafficking at the IHC presynapse. They also noted significant developmental changes in this molecular profile by measuring proteins before and after the onset of hearing. The group further validated the proteins by confocal microscopy but they say that more needs to be done. Knocking down these proteins in animal models along with recent advances in the study of membrane trafficking could reveal key synaptic physiology contributing to deafness.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.