Study reveals experimental targets for lymphoma research

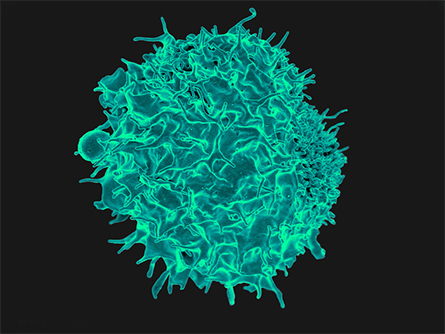

Lymphocytes, white blood cells made in the bone marrow, are an essential part of the immune system. The two main types of lymphocytes, T cells and B cells, carry out an adaptive immune response. B cells target circulating pathogens in the body, and T cells manage cell response to infection.

National Institutes of Health

that arise during their production in the bone marrow can lead to lymphomas.

During the production of these immune cells, called hematopoiesis, mutations can lead to T-cell or B-cell lymphomas. During hematopoiesis, genes sometimes are said to be turned "on" or "off" through a biological process called DNA methylation. This occurs when a methyl group is added to the DNA power switch that controls the expression of that gene. A family of enzymes called DNA methyltransferases, or Dnmts, carries out this process and is an important part of cellular function.

A new study in the Journal of Biological Chemistry reports that one DNA methylation enzyme, Dnmt3b, suppresses the development of lymphomas through its catalytic and noncatalytic functions. The authors, researchers at the universities of Florida and Nebraska, also provide evidence for a molecular pathway possibly involved in lymphoma development related to mutated Dnmt3b.

Previous research linked mutations to Dnmt3b with lymphoma development — alongside other diseases that impair the immune system. Dnmt3b influences the expression or silencing of genes, an important aspect for cancer research, as Dnmt3b suppresses tumor development. Decreased activity of Dnmt3b is linked to a rare disease called immunodeficiency-centromeric instability-facial anomalies syndrome and also human chronic lymphocytic leukemia, leading researchers to wonder if loss of Dnmt3b catalytic activity is a major factor in blood cancer.

Katarina Lopusna and colleagues investigated the significance of Dnmt3b in lymphoma using several experimental mouse models. The researchers generated mice lacking Dnmt3b's catalytic activity for one or both of the genetic alleles and compared them to mice with only one Dnmt3b allele. Knocking out one allele of Dnmt3b decreases all of its functions, including accessory jobs such as recruiting other Dnmts or influencing gene expression (outside of methylation). Taking away the catalytic activity of Dnmt3b, even partially, should hinder DNA methylation specifically, reducing production of blood cells and possibly tumorigenesis.

This study design yielded unexpected results for lymphoma development, according to Eric Fearon, an associate editor for the Journal of Biological Chemistry. "(In) an interesting twist … mice heterozygous for a null (complete loss-of-function) Dnmt3b allele developed T-cell malignancies," Fearon wrote in an email. "In contrast, mice that expressed a Dnmt3b allele encoding a DNMT3b protein that lacked catalytic activity developed B-cell malignancies."

These findings demonstrate that both the catalytic activity and accessory functions of Dnmt3b are important for fighting cancer.

The researchers investigated molecular mechanisms that could explain the link between Dnmt3b and blood cancer. Genomewide analysis revealed decreased methylation and increased expression of tumor-promoting genes. The results also showed reduced expression of the p53 pathway, known for preventing T-cell transformation.

The researchers' efforts "highlight how careful analysis of mutant alleles in mouse models can yield insights into the potential non-catalytic functions of certain enzymes, such as Dnmt3b," Fearon wrote. The study also puts forth potential molecular targets that may contribute to Dnmt3b-related tumor development for future research.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.