Innovative platform empowers scientists to transform venoms into therapeutics

Some of the most successful and effective drugs, like Ozempic, come from animal venoms. However, scientists usually only discover the therapeutic potential of venoms by chance. Recently, an international group of researchers, led by Meng-Hsuan Hsiao of Ben Larman ’s laboratory at Johns Hopkins University, set out to change that by developing a workflow to accelerate drug discovery from peptides, or short sequences of amino acids, with sequences and structures that resemble animal venoms. They published their study in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

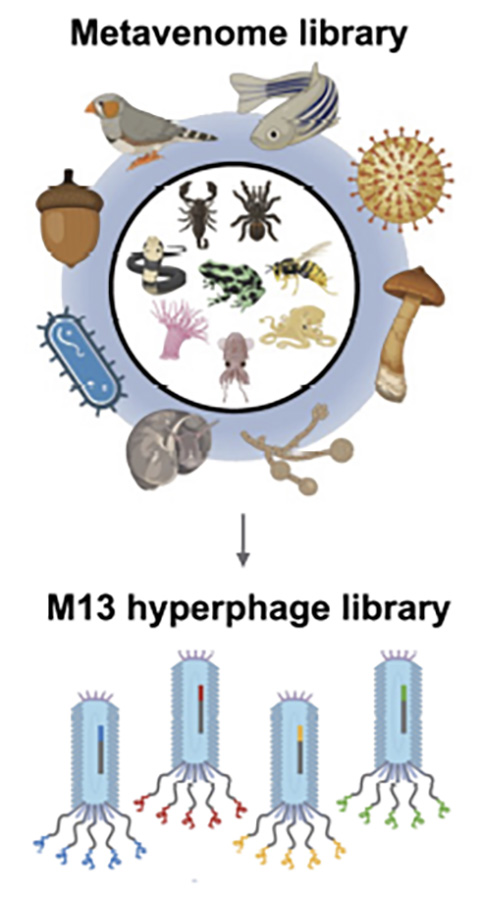

Hsiao and colleagues demonstrated that their platform could evaluate over 10,000 venom-like peptides’ ability to bind specific receptors on human cells. Larman’s group teamed up with Martin Steinegger, an assistant professor at Seoul National University, who built a “metavenome library” from known animal venom sequences and additional peptides based on sequence homology.

“A library allows us to explore a much larger space of possible lead compounds for drugs,” Larman said. “You don’t even need to have a starting hypothesis.”

The researchers expressed peptides from this library on the surface of bacteriophages, or bacteria-infecting viruses, a technique also known as phage display. For their platform, Larman’s team used what he called a specific “flavor” of phage: the M13 hyperphage.

Hyperphages carry genetic mutations that make them display five copies of venom-like peptides on their surface. Therefore, the displayed peptides could interact with multiple receptors, amplifying the signal and allowing the researchers to detect weaker interactions.

“The way we used hyperphages to display venoms has never been done before,” said Larman.

Unlike other phages, M13 phages are secreted through the bacterial periplasm, the space between the bacteria’s inner and outer cell membranes. The periplasm has an oxidizing chemical environment, Larman explained, and this helps preserve the venom peptides’ disulfide bonds, which are critical for their 3D structures. These disulfide bonds make venoms attractive therapeutics because they are highly compact and resistant to degradation.

Using their platform, Larman’s team identified six proteins in the metavenome library that bind and activate the human itch receptor MAS-related G protein-coupled receptor X4, or MRGPRX4. They found that these proteins share a unique folding pattern called the Kunitz domain, which is commonly known to inhibit serine protease activity. In the future, Larman’s team plans to expand their metavenome library to include even more peptides in search of a potent MRGPRX4 antagonist that can be developed into an anti-itch drug.

“I think that if you can find an agonist, you can also find an antagonist,” Larman said, “And we can likely achieve this by expanding our library.”

Larman said he hopes to integrate generative artificial intelligence into their system to broaden the library to include novel venom-like peptides.

“Once set up and integrated,” he said. “I can see this cycle of computational prediction and experimental validation being really powerful in drug discovery.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.