Search for a major depression trigger reveals a familiar face

A common amino acid, glycine, can deliver a strong signal to the brain, likely helping alleviate major depression, anxiety and other mood disorders in some people, scientists at The Herbert Wertheim UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology report online in the journal Science today.

The discovery improves understanding of the biological causes of major depression and could accelerate efforts to develop new, faster-acting medications for such hard-to-treat mood disorders, said neuroscientist Kirill Martemyanov, corresponding author of the study, appearing in Friday’s edition.

“There are limited medications for people with depression,” said Martemyanov, who chairs the neuroscience department at the institute. “Most of them take weeks before they kick in, if they do at all. New and better options are really needed.”

Major depression is among the world’s most urgent health needs. Its numbers have surged in recent years, especially among young adults. As depression’s disability, suicide numbers and medical expenses have climbed, a study by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2021 put its economic burden at $326 billion annually in the United States.

Martemyanov said he and his team of students and postdoctoral researchers have spent many years working toward this discovery.

They didn’t set out to find a cause, much less a possible treatment route for depression. Instead, they asked a basic question: How do sensors on brain cells receive and transmit signals into the cells, and then change the cells’ activity? Therein lay the key to understanding vision, pain, memory, behavior and possibly much more, Martemyanov suspected.

“It’s amazing how basic science goes. Fifteen years ago we discovered a binding partner for proteins we were interested in, which led us to this new receptor,” Martemyanov said. “We’ve been unspooling this for all this time.”

In 2018 the Martemyanov team found the new receptor was involved in stress-induced depression. If mice lacked the gene for the receptor, called GPR158, they proved surprisingly resilient to chronic stress.

That offered strong evidence that GPR158 could be therapeutic target, he said. But what sent the signal?

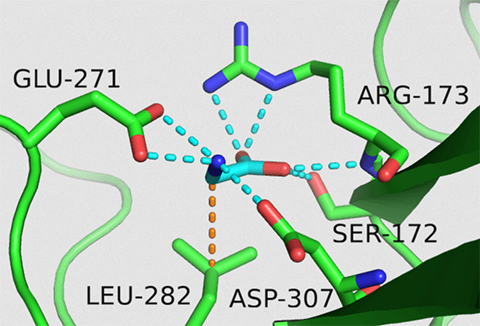

A breakthrough came in 2021, when his team solved the structure of GPR158. What they saw surprised them. The GPR158 receptor looked like a microscopic clamp with a compartment — akin to something they had seen in bacteria, not human cells.

“We were barking up the completely wrong tree before we saw the structure,” Martemyanov said. “We said, ‘Wow, that’s an amino acid receptor. There are only 20, so we screened them right away and only one fit perfectly. That was it. It was glycine.”

That wasn’t the only odd thing. The signaling molecule was not an activator in the cells, but an inhibitor. The business end of GPR158 connected to a partnering molecule that hit the brakes rather than the accelerator when bound to glycine.

“Usually receptors like GPR158, known as G protein coupled receptors, bind G proteins. This receptor was binding an RGS protein, which is a protein that has the opposite effect of activation,” said Thibaut Laboute, a postdoctoral researcher from Martemyanov’s group and first author of the study.

Scientists have been cataloging the role of cell receptors and their signaling partners for decades. Those that still don’t have known signalers, such as GPR158, have been dubbed “orphan receptors.”

The finding means that GPR158 is no longer an orphan receptor, Laboute said. Instead, the team renamed it mGlyR, short for “metabotropic glycine receptor.”

“An orphan receptor is a challenge. You want to figure out how it works,” Laboute said. “What makes me really excited about this discovery is that it may be important for people’s lives. That’s what gets me up in the morning.”

Glycine itself is sold as a nutritional supplement billed as improving mood. It is a basic building block of proteins and affects many different cell types, sometimes in complex ways. In some cells, it sends slow-down signals, while in other cell types, it sends excitatory signals. Some studies have linked glycine to the growth of invasive prostate cancer.

More research is needed to understand how the body maintains the right balance of mGlyR receptors and how brain cell activity is affected, he said. He intends to keep at it.

“We are in desperate need of new depression treatments,” Martemyanov said. “If we can target this with something specific, it makes sense that it could help. We are working on it now.”

This article was first published by the University of Florida. Read the original.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.