The sweet tale of a silkworm taste receptor

Taste has evolved as the predominant driver of insect feeding behavior. Taste-sensing mechanisms not only help insects distinguish between food and toxins but also play a role in courtship, mating and egg laying.

Scientists have identified taste receptors in insects, called gustatory receptors, as proteins having seven transmembrane domains, like G-protein coupled receptor, or GPCR. These receptors recognize and bind many molecules, from sugars to bitter substances.

Kazushige Touhara and his team at the University of Tokyo have been studying the mechanisms by which insects sense taste and smell.

In their recent study published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, research assistant Satoshi Morinaga and colleagues built upon the lab’s past research and proposed a model for recognizing the fruit sugar d-fructose by the BmGr9 taste receptor.

Endopterygotes, insects such as moths and butterflies, develop wings inside their bodies and undergo complete metamorphosis through egg, larval, pupal and adult stages. In previous research, the Touhara lab found that the silkworm’s BmGr9 taste receptor is a d-fructose–gated ion channel receptor not categorized as a GPCR but conserved within endopterygotes as a distinct family of receptors.

“We reported that an insect gustatory receptor looks like a ligand-gated channel distinct from a mammalian GPCR, which makes us very interested in this receptor family,” Morinaga said. “The gustatory receptor appears to be a ligand-gated ion channel with the seven transmembrane topology that is reversed from that of a GPCR.”

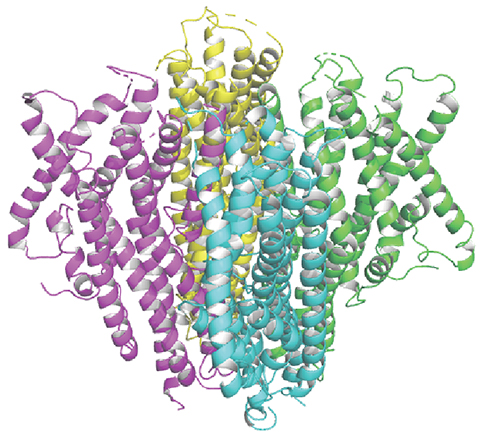

Using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, the authors observed that BmGr9 exists in cells as a group of four, or a homotetramer, similar to that of an insect odorant receptor coreceptor called Orco. They also found that the orientation of Orco and BmGr9’s protein ends had similarities relative to the inner or outer sides of the cell membrane.

Based on these similarities, the team used a previously solved cryo-EM structure of Orco from Apocrypta bakeri, a species of fig wasps, to predict the structure of BmGr9 using homology modeling.

“We constructed a structural model for a gustatory receptor based on the structure of a known olfactory receptor,” Morinaga said. “Along with biochemical and site-directed mutagenesis studies, we provide for the first time a structural model for an insect gustatory receptor and a mode for sugar binding.”

Like BmGr9 and Orco, the olfactory receptor OR5 in an ancient insect, the jumping bristletail, or Machilis hrabei, also exists as a homotetramer and is an odorant-gated ion channel. The OR5 receptor binds the odorant eugenol.

To compare the ligand-binding modes of BmGr9 and OR5, the BmGr9 and OR5 structures were superimposed. The study reports that the amino acid residues essential for d-fructose responses in BmGr9 correlate with the position of amino acids in the OR5 receptor that senses eugenol.

“We also provide insight into a conformational change that leads to a channel opening after sugar binding to the receptor,” Morinaga said. “This receptor is activated by d-fructose very selectively, and the next step is determining how the high selectivity is established.”

The proposed mechanism of d-fructose recognition and binding by BmGr9 will help the researchers determine the 3D structure of BmGr9, which will validate this study further.

“The knowledge of an insect gustatory sensing system will be useful to develop compounds that have an aversive effect on insects that eat and damage our farm crops,” Morinaga said.

The Touhara lab’s long-term goal is to study other gustatory receptors, such as sucrose and bitter receptors.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.