From the journals: JLR

How does gastric bypass affect microRNA production? How does adiponectin fight fatty plaques? How is ceramide concentration sensed in cilia? We offer summaries of recent papers from the Journal of Lipid Research addressing these questions.

Gastric bypass affects microRNA production

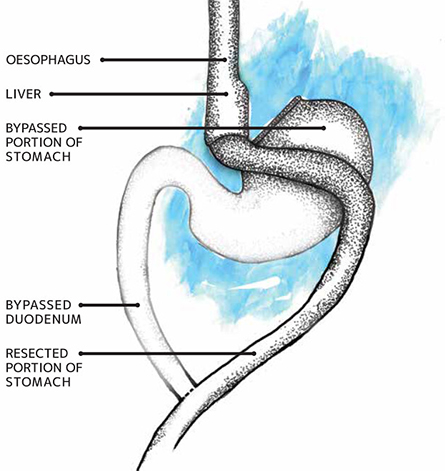

Over one-third of people in the United States are obese, putting them at increased risk for heart disease, stroke, diabetes and certain cancers. Bariatric surgeries, procedures performed on the stomach or intestines to induce weight loss, can help these individuals lose weight. The most commonly performed weight loss surgery, a gastric bypass, creates a small pouch from the stomach that connects directly to the small intestine. After the surgery, the usable portion of the stomach is very small, limiting the amount a person can eat. In addition, swallowed food bypasses most of the stomach and some of the small intestine, causing less food to be absorbed.

pouch and connected directly to the small intestine, a process that decreases nutrient

absorption and eventually leads to weight loss.

Even before they lose weight, patients' metabolic and cardiovascular systems function better after the surgery. Jan Hoong Ho at the University of Manchester and a team of British and Australian researchers have discovered how high-density lipoprotein, or HDL, the so-called "good cholesterol," might be involved in this phenomenon.

Lipoproteins are small particles that carry cholesterol, other lipids, proteins and nucleic acid cargo between cells. HDL is considered helpful because it transports cholesterol out of tissues and to the liver, where it can be neutralized. However, researchers do not yet understand exactly how HDL controls the removal of cholesterol from tissues. Recently, researchers have found that HDL particles can carry microRNAs, short RNAs that impede the expression of genes. In a recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research, Ho and colleagues demonstrate that the microRNAs within HDL particles may confer the protective effects of gastric bypass.

The group showed that HDL's cholesterol efflux capacity is improved after gastric bypass, independent of weight loss, and that this improved function correlates with the levels of certain microRNAs within the HDL particle. The discovery of microRNAs that regulate the removal of cholesterol from tissues gives researchers a potential therapeutic avenue in the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders.

How adiponectin fights fatty plaques

The formation of fatty plaques in the arteries, called atherogenesis, can lead to problems such as heart attack, stroke or even death. Fat cells, called adipocytes, secrete a protein called adiponectin into the bloodstream, where it can block these fatty plaques from forming, but researchers do not yet know how adiponectin performs this protective function. In a recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research, investigator Akemi Kakino from Shinshu University and a team of Japanese researchers describe how adiponectin protects against atherogenesis by blocking the uptake of specific types of low-density lipoprotein, or LDL, that have atherogenic properties.

These atherogenic varieties, such as oxidized LDL and electronegative LDL, enter cells via scavenger receptors and trigger a cell signaling cascade that causes plaque formation. The researchers found that the more adiponectin there was in the cell culture medium, the less efficiently LDL could gain entry into the cells. The decrease in plaque-causing LDL uptake led to lower levels of LDL-induced atherogenic signaling cascades. The authors used the same concentrations of adiponectin found in the human body, strongly supporting the idea that blocking atherogenic LDL uptake is a physiological function of the protein and not just something that occurs in artificial laboratory conditions. Overall, the results provide insights into how adiponectin protects us from developing fatty arteries and offer a new therapeutic target in the treatment of atherosclerosis-related diseases.

Ceramide anchors cilia proteins

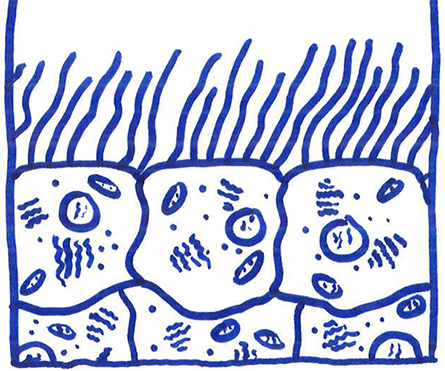

Cellular cilia depend on an axle-and-spoke arrangement of microtubules for structural integrity, meaning that to generate cilia, a cell must synchronize microtubule and membrane extension. The plasma membrane lipid ceramide regulates the length of cilia and transport along growing cilia, but researchers have been uncertain of how ceramide concentration is sensed.

are built.

In a recent article in the Journal of Lipid Research, Priyanka Tripathi and a team from the University of Kentucky report that lipid modification of cysteine residues on a microtubule protein allows direct binding to ceramide in the membrane. Microtubules are made up of two subunits, alpha tubulin and beta tubulin, each of which can be post-translationally modified. A subset of acetylated alpha tubulin is palmitoylated, and the researchers showed using immunoprecipitation and fluorescence microscopy that palmitoylation allows tubulin to bind to ceramide. It also helps tubulin recruit a GTPase involved in protein transport into the cilia.

The authors report that the interaction between ceramide and palmitoyl-tubulin is required for new cilia to form in human-derived neural progenitor cells, where they eventually mature into dendrites and axons. The interaction is also necessary for a distantly related eukaryotic algae to grow flagella.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.