JBC: Paving the way for disease-resistant rice

Researchers have uncovered an unusual protein activity in rice that might give plants an edge in the evolutionary arms race against rice blast disease, a major threat to rice production.

Magnaporthe oryzae, the fungus that leads to the disease, creates lesions on rice plants that reduce the yield and quality of grain, causing a loss of up to a third of the annual global rice harvest.

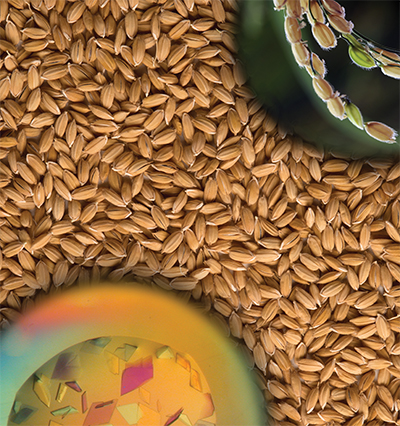

Protein crystals and a rice panicle depicted against a backdrop of rice grains represent the structural biology and plant pathology aspects of a study that found a new way to combat rice blast disease. Marina Franceshetti and Phil Robinson

Protein crystals and a rice panicle depicted against a backdrop of rice grains represent the structural biology and plant pathology aspects of a study that found a new way to combat rice blast disease. Marina Franceshetti and Phil Robinson

A sustainable approach to ward off the fungus has not yet been developed. Cost and environmental concerns limit the use of toxic fungicides. And a phenomenon called linkage drag, where undesirable genes are transferred along with desired ones, makes it difficult to breed varieties with improved disease resistance that still produce grain at a desired rate.

Gene-editing technologies that precisely insert genes in rice plants eventually could overcome linkage drag, but first, genes that boost rice immunity need to be identified or engineered.

Mark Banfield at the John Innes Centre and a team of researchers in Japan and the U.K. report in the Journal of Biological Chemistry that a particular rice immune receptor — from a class of receptors that typically recognize single pathogenic proteins — triggers immune reactions in response to two fungal proteins. The genes encoding this receptor could become a template for engineered receptors that detect multiple fungal proteins and thereby improve disease resistance.

Rice blast fungus deploys proteins known as effectors inside rice cells. In response, rice plants have evolved genes that encode nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat proteins, or NLRs, which are intracellular immune receptors that bait specific fungal effectors. After an NLR receptor’s specific fungal effector binds to the bait, signaling pathways are initiated that cause cell death.

The cells “die in a very localized area so the rest of the plant is able to survive,” Banfield said. “It’s almost like sacrificing your finger to save the rest of your body.”

After learning that the fungal effectors AVR-Pia and AVR-Pik have similar structures, the researchers sought to find out whether any rice NLRs known to bind to one of these effectors might also bind to the other, Banfield said.

The team introduced different combinations of rice NLRs and fungal effectors into tobacco (a model for studying plant immunity) and also used rice plants to show if any unusual pairs could elicit immune responses. An AVR-Pik-binding rice NLR called Pikp triggered cell death in response to AVR-Pik as expected, but the experiments showed that plants expressing this NLR also partially reacted to AVR-Pia.

Looking at the unexpected pairing using X-ray crystallography, the authors saw that the rice NLR possessed two separate docking sites for AVR-Pia and AVR-Pik.

Pikp causes meager immune reactions after binding AVR-Pia; however, the receptor’s DNA could be modified to improve its affinity for mismatched effectors, Banfield said. “If we can find a way to harness that capability, we could produce a super NLR that’s able to bind multiple pathogen effectors.”

As an ultimate endgame, gene-editing technologies could be used to insert enhanced versions of NLRs — such as Pikp — into plants, Banfield said, which could tip the scale in favor of healthy rice crops.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.