Helping mitochondria run smoothly may protect against Parkinson’s disease

In 1817, a British physician named James Parkinson published An Essay on the Shaking Palsy, describing for the first time cases of a neurodegenerative disorder now known as Parkinson’s disease. Today, Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disease in the U.S. It affects about 1 million Americans and more than 10 million people worldwide.

The signature shaking in patients with the disease is the result of dying brain cells that control movement. To date, there are no treatments available that can stop or slow down the death of those cells.

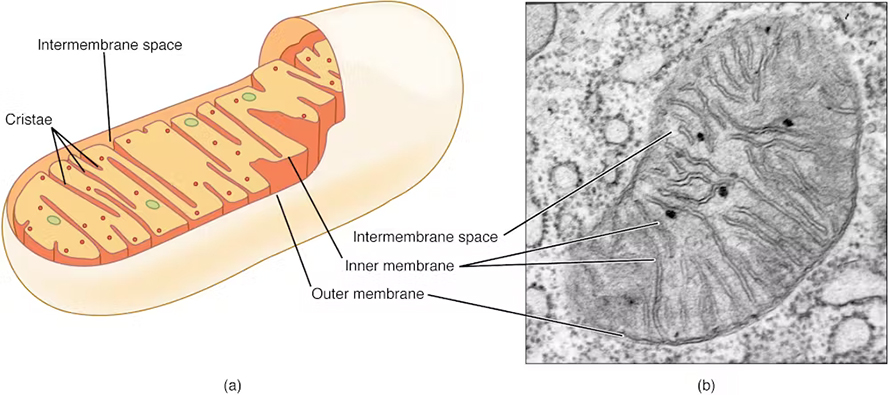

We are researchers who study Parkinson’s disease. For over a decade, our lab has been investigating the role that mitochondria – the powerhouses that fuel cells – play in Parkinson’s.

Our research has identified a key protein that could lead to new treatments for Parkinson’s disease and other brain conditions.

Mitochondrial dynamics and neurodegeneration

Unlike actual power plants, which are set in size and location, mitochondria are rather dynamic. They constantly shift in size, number and location, traveling between many different parts of the cells to meet different demands. These mitochondrial dynamics are vital to not only the function of mitochondria but also the health of cells overall.

A cell is like a factory. Multiple departments must seamlessly work together for smooth operations. Because many major processes interconnect, impaired mitochondrial dynamics could cause a domino effect across departments and vice versa. Collective malfunction in different parts of the cell eventually leads to cell death.

Emerging studies have linked imbalances in mitochondrial processes to different neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease. In many neurodegenerative disorders, certain disease-related factors, such as toxic proteins and environmental neurotoxins, disrupt the harmony of mitochondrial fusion and division.

Impaired mitochondrial dynamics also take down the cell’s cleaning and waste recycling processes, leading to a pileup of toxic proteins that form harmful aggregates inside the cell. In Parkinson’s, the presence of these toxic protein aggregates is a hallmark of the disease.

Targeting mitochondria to treat Parkinson’s

Our team hypothesized that restoring mitochondrial function by manipulating its own dynamics could protect against neuronal dysfunction and cell death.

In an effort to restore mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s, we targeted a key protein that controls mitochondrial dynamics called dynamin-related protein 1, or Drp1. Naturally abundant in cells, this protein travels to mitochondria when they divide into smaller sizes for higher mobility and quality control. However, too much Drp1 activity causes excessive division, leading to fragmented mitochondria with impaired function.

Using different lab models of Parkinson’s, including neuronal cell cultures and rat and mice models, we found that the presence of environmental toxins and toxic proteins linked to Parkinson’s cause mitochondria to become fragmented and dysfunctional. Their presence also coincided with the buildup of those same toxic proteins, worsening the health of neuronal cells until they eventually started dying.

We also observed behavior changes in rats that impaired their movements. By reducing the activity of Drp1, however, we were able to restore mitochondria to their normal activity and function. Their neurons were protected from disease and able to continue functioning.

In our 2024 study, we found an additional benefit of targeting Drp1.

We exposed neuronal cells to manganese, a heavy metal linked to neurodegeneration and an increased risk of parkinsonism. Surprisingly, we found that manganese was more harmful to the cell’s waste recycling system than to its mitochondria, causing buildup of toxic proteins before mitochondria became dysfunctional. Inhibiting Drp1, however, coaxed the waste recycling system back into action, cleaning up toxic proteins despite the presence of manganese.

Our findings indicate that inhibiting Drp1 from more than one pathway could protect cells from degeneration. Now, we’ve identified some FDA-approved compounds that target Drp1 and are testing them as potential treatments for Parkinson’s.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.