Social stress can speed up immune system aging

As people age, their immune systems naturally begin to decline. This aging of the immune system, called immunosenescence, may be an important part of such age-related health problems as cancer and cardiovascular disease, as well as older people’s less effective response to vaccines.

But not all immune systems age at the same rate. In our recently published study, my colleagues and I found that social stress is associated with signs of accelerated immune system aging.

Stress and immunosenescence

To better understand why people with the same chronological age can have different immunological ages, my colleagues and I looked at data from the Health and Retirement Study, a large, nationally representative survey of U.S. adults over age 50. HRS researchers ask participants about different kinds of stressors they have experienced, including stressful life events, such as job loss; discrimination, such as being treated unfairly or being denied care; major lifetime trauma, such as a family member’s having a life-threatening illness; and chronic stress, such as financial strain.

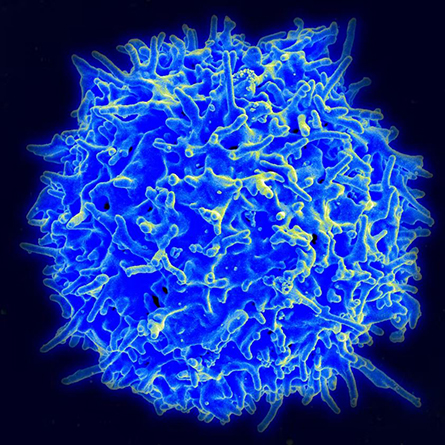

Recently, HRS researchers have also started collecting blood from a sample of participants, counting the number of different types of immune cells present, including white blood cells. These cells play a central role in immune responses to viruses, bacteria and other invaders. This is the first time such detailed information about immune cells has been collected in a large national survey.

pathogens.

By analyzing the data from 5,744 HRS participants who both provided blood and answered survey questions about stress, my research team and I found that people who experienced more stress had a lower proportion of “naive” T cells – fresh cells needed to take on new invaders the immune system hasn’t encountered before. They also have a larger proportion of “late differentiated” T cells – older cells that have exhausted their ability to fight invaders and instead produce proteins that can increase harmful inflammation. People with low proportions of newer T cells and high proportions of older T cells have a more aged immune system.

After we controlled for poor diet and low exercise, however, the connection between stress and accelerated immune aging wasn’t as strong. This suggests that improving these health behaviors might help offset the hazards associated with stress.

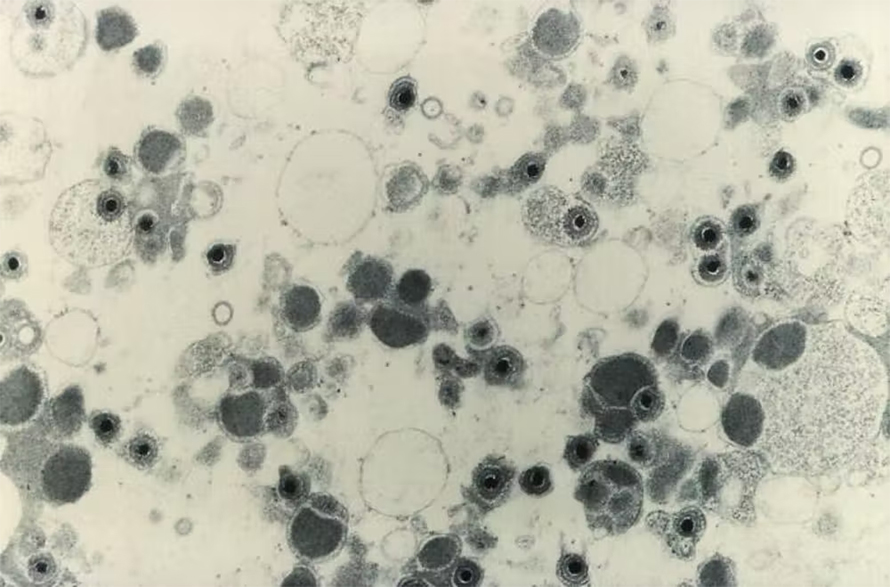

Similarly, after we accounted for potential exposure to cytomegalovirus – a common, usually asymptomatic virus known to accelerate immune aging – the link between stress and immune cell aging was reduced. While CMV normally stays dormant in the body, researchers have found that stress can cause CMV to flare up and force the immune system to commit more resources to control the reactivated virus. Sustained infection control can use up naive T cell supplies and result in more exhausted T cells that circulate throughout the body and cause chronic inflammation, an important contributor to age-related disease.

Understanding immune aging

Our study helps clarify the association between social stress and faster immune aging. It also highlights potential ways to slow down immune aging, such as changing how people cope with stress and improving lifestyle behaviors like diet, smoking and exercise. Developing effective cytomegalovirus vaccines may also help alleviate immune system aging.

It is important to note, however, that epidemiological studies cannot completely establish cause and effect. More research is needed to confirm whether stress reduction or lifestyle changes will lead to improvements in immune aging, and to better understand how stress and latent pathogens like cytomegalovirus interact to cause illness and death. We are currently using additional data from the Health and Retirement Study to examine how these and other factors like childhood adversity affect immune aging over time.

Less aged immune systems are better able to fight infections and generate protective immunity from vaccines. Immunosenescence may help explain why people are likely to have more severe cases of COVID-19 and a weaker response to vaccines as they age. Understanding what influences immune aging may help researchers better address age-related disparities in health and illness.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.