How a complex molecule moves iron through the body

New research provides fresh insight into how an important class of molecules are created and moved in human cells.

For years, scientists knew that mitochondria — specialized structures inside cells in the body that are essential for respiration and energy production — were involved in the assembly and movement of iron-sulfur cofactors, some of the most essential compounds in the human body. But until now, researchers didn’t understand how exactly the process worked.

New research, published in the journal Nature Communications, found that these cofactors are moved with the help of a substance called glutathione, an antioxidant that helps prevent certain types of cell damage by transporting these essential iron cofactors across a membrane barrier.

Glutathione is especially useful as it aids in regulating metals like iron, which is used by red blood cells to make hemoglobin, a protein needed to help carry oxygen throughout the body, said James Cowan, co-author of the study and a distinguished university professor emeritus in chemistry and biochemistry at Ohio State.

“Iron compounds are critical for the proper functioning of cellular biochemistry, and their assembly and transport is a complex process,” Cowan said. “We have determined how a specific class of iron cofactors is moved from one cellular compartment to another by use of complex molecular machinery, allowing them to be used in multiple steps of cellular chemistry.”

Iron-sulfur clusters are an important class of compounds that carry out a variety of metabolic processes, like helping to transfer electrons in the production of energy and making key metabolites in the cell, as well as assisting in the replication of our genetic information.

“But when these clusters don't work properly, or when key proteins can’t get them, then bad things happen,” Cowan said.

If unable to function, the corrupted protein can give rise to several diseases, including rare forms of anemia, Friedreich’s ataxia (a disorder that causes progressive nervous system damage), and a multitude of other metabolic and neurological disorders.

So to study how this essential mechanism works, researchers began by taking a fungus called C. thermophilum, identifying the key protein molecule of interest, and producing large quantities of that protein for structural determination. The study notes that the protein they studied within C. thermophilum is essentially a cellular twin of the human protein ABCB7, which transfers iron-sulfur clusters in people, making it the perfect specimen to study iron-sulfur cluster export in people.

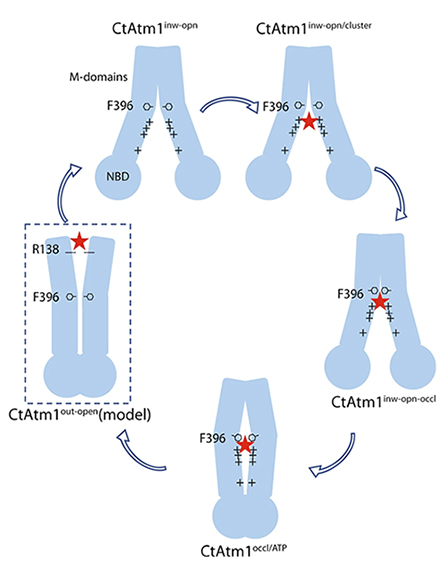

By using a combination of cryo-electron microscopy and computational modeling, the team was then able to create a series of structural models detailing the pathway that mitochondria use to export the iron cofactors to different locations inside the body. While their findings are vital to learning more about the basic building blocks of cellular biochemistry, Cowan said he’s excited to see how their discovery could later advance medicine and therapeutics.

“By understanding how these cofactors are assembled and moved in human cells, we can lay the groundwork for determining how to prevent or alleviate symptoms of certain diseases,” he said. “We can also use that fundamental knowledge as the foundation for other advances in understanding cellular chemistry.”

This article was republished with permission from The Ohio State University. Read the original.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.