JBC: Antibiotic resistance in pandemic cholera

Cholera is a devastating disease for millions worldwide, primarily in developing countries, and the dominant type of cholera today is naturally resistant to one type of antibiotic usually used as a treatment of last resort.

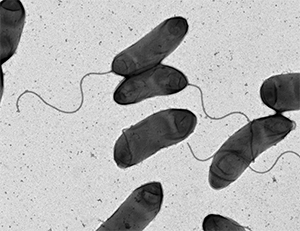

This image shows an electron micrograph of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera. courtesy of M. Stephen Trent/University of Georgia

This image shows an electron micrograph of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera. courtesy of M. Stephen Trent/University of Georgia

Researchers at the University of Georgia now have shown that the enzyme that makes the El Tor family of Vibrio cholera resistant to those antibiotics has a different mechanism of action from any comparable proteins observed in bacteria so far. Understanding that mechanism better equips researchers to overcome the challenge it presents in a world with increasing antibiotic resistance. The research was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Cationic antimicrobial peptides, or CAMPs, are produced naturally by bacteria and by animals’ innate immune systems and also are synthesized for use as last-line drugs. Cholera strains achieve resistance to CAMPs by chemically disguising the bacterium’s cell wall, which prevents CAMPs from binding, disrupting the wall and killing the bacterium. M. Stephen Trent’s research team in Georgia previously had shown that a group of three proteins carried out this modification and had elucidated the functions of two of the proteins. The team reported the role of the third protein — the missing piece in understanding CAMP resistance — in the new paper.

Jeremy Henderson, then a graduate student, led a research project that showed that this enzyme, AlmG, attaches glycine, the smallest of the amino acids, to lipid A, one of the components of the outer membrane of the bacterial cell. This modification changes the charge of the lipid A molecules, preventing CAMPs from binding.

Lipid A modification is a defense mechanism observed in other bacteria, but detailed biochemical characterization of AlmG showed that the way this process occurred in cholera was unique.

“It became apparent over the course of our work that how (this enzyme) improves shield functionality is quite different than would be expected based on what we know about groups of enzymes that look similar,” Henderson said.

AlmG is structured differently from other lipid A-modifying enzymes, with a different active site responsible for carrying out the modification. In addition, AlmG can add either one or two glycines to the same lipid A molecule, which also has not been observed in other bacteria. “It just opens up the door for this operating with a completely different mechanism than what’s been described in the literature for related proteins,” Henderson said.

Genes encoding determinants of antibiotic resistance can spread between different species of bacteria, so the unique mechanism of CAMP drug resistance in V. cholerae is of potential concern if it jumps to bacteria already resistant to first-line drugs. “The level of protection conferred by this particular modification in Vibrio cholerae puts it in a league of its own,” Henderson said.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)