A novel approach to septic shock leads to a prospective new therapy

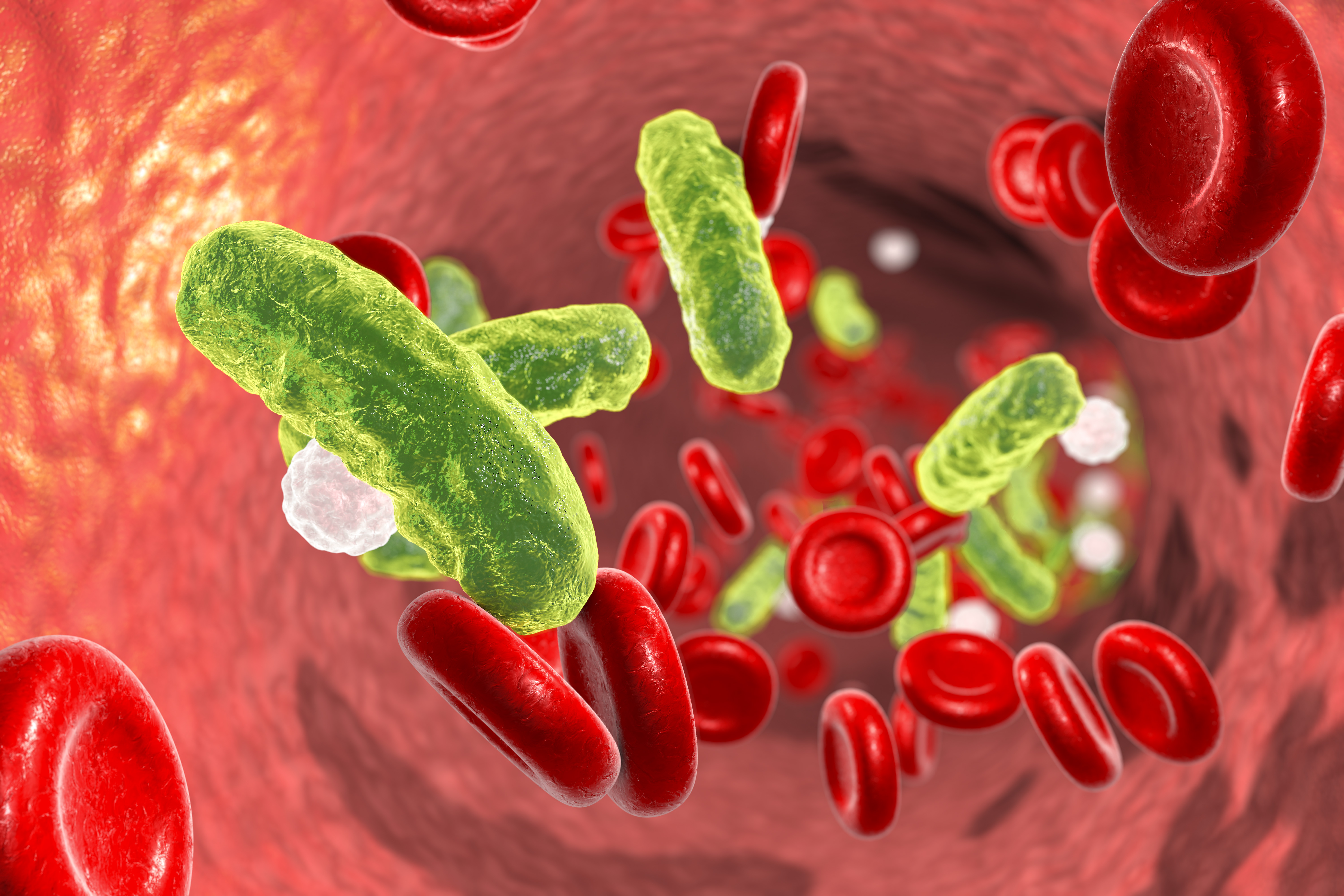

The human body responds to infection by activating its innate immune system. Sepsis occurs when that triggered immune response spins out of control and becomes life-threatening. Doctors administer antibiotics and other supportive care but are unable to prevent death in about 40% of sepsis patients. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that some 270,000 patients in the United States die from sepsis each year.

When antibiotics are not enough, clinicians need another line of treatment to improve patient outcomes. A recent publication in the Journal of Lipid Research by Auguste Dargent of the Centre Hospitalier de Lyon in France and colleagues details their efforts in response to failed clinical trials investigating a toxin removal method for sepsis treatment.

Septic shock most commonly is caused by bacterial infections. Bacteria express certain toxins that provoke the immune system during sepsis, including lipopolysaccharides, or LPS. The researchers thought lowering the level of LPS in the blood could treat septic shock more effectively than antibiotics alone.

As Kenneth Feingold, a JLR associate editor, explained, “LPS is a part of gram-negative bacteria, which is the etiology of most sepsis … If one can bind up the LPS that comes off this bacteria, then this can potentially reduce the number of deaths from sepsis.”

The body already has molecules in charge of clearing out LPS called lipoproteins. High-density lipoproteins grab onto LPS in the blood and pass them over to low-density lipoproteins, or LDLs, which take them to the liver for degradation.

However, as the research team previously had discovered, this built-in protection fails in septic patients with decreased lipoprotein levels. They also showed that treating with a therapeutic protein that promotes LPS clearance can improve mortality rates in septic animals. These findings led them to investigate whether the same is true in humans.

To test their hypothesis, the researchers loaded blood plasma samples from healthy patients with LPS, a process called “spiking.” Then they soaked spiked samples in a solution with tiny beads that grab onto LDL, a lipoprotein with an LPS attached, and remove it from the plasma.

To determine the amount of LDL left over in the plasma, the team measured the amount of 3-hydroxymyristate, an LPS lipid component. Doing so allowed for direct measurement of LPS plasma levels, whether bound to a lipoprotein or circulating freely. With this, they saw a decrease in free LPS and LDL levels in treated samples — inspiring researchers to look further into cholesterol disorders.

Patients with familial hypercholesterolemia have high levels of LDLc in their blood. Researchers examined serum samples from hypercholesterolemia patients undergoing treatment with the same or similar microbead-removal methods. These patients also saw a significant drop in their LDLc and LPS levels after treatment.

These results prompted the researchers to examine their strategy in serum samples collected from septic patients. They remained successful in removing circulating LPS from plasma samples using microbeads — a promising result for this team to build on moving forward.

“The key is that this is the first step,” Feingold said. He emphasized that studies in animal models are needed to determine whether this therapeutic approach can be developed as treatment for sepsis. “If successful, this could be a major advance. But we have to see if this actually works.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.