How lipid metabolism shapes sperm development

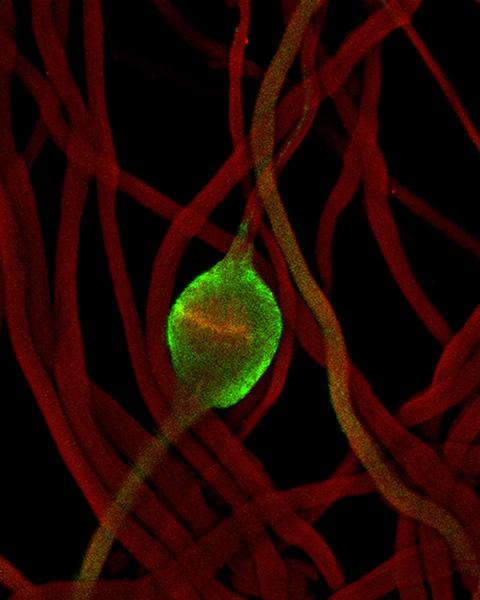

Sperm cells are among the most specialized in the body, designed for a single purpose: fertilization. Each carries DNA and propels itself toward an egg using a whip-like tail called a flagellum. Inside the testes, sperm develop through several well-defined stages, acquiring the structures and molecules needed for fertilization.

One crucial part of this transformation is the production of seminolipids, specialized fats found in developing sperm that are essential for their formation and function. Seminolipids are synthesized by fatty acyl-CoA reductase, or FAR, enzymes. Mammals have two different FAR enzymes, FAR1 and FAR2.

Although both FAR1 and FAR2 are known to synthesize fatty alcohols, their specific roles in seminolipid production had remained unclear. To pinpoint which enzyme was responsible, Ayano Tamazawa and colleagues at Hokkaido University analyzed mice lacking Far1 and Far2 to clarify their roles in seminolipid production and spermatogenesis. They found that loss of Far1 led to a dramatic decrease in seminolipids and impaired sperm development. The study was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Tamazawa said the findings show how the loss of seminolipids disrupts spermatogenesis, emphasizing the critical role of ether linkages in sperm development.

Seminolipids are categorized by the types of alkyl and acyl chains they contain, which differ in length and saturation. The most common seminolipid in the testis is O-C16:0/C16:0. Using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, or LC–MS/MS, the researchers mapped the exact structure of these lipids.

High-resolution lipidomics analysis of seminolipids and SGalDAGs (3-sulfogalactosyl-1-acyl-2-acylglycerols) showed that both lipid types have similar side chains composed of saturated acyl or alkyl groups. The main difference is that SGalDAGs have a 1-acyl group, whereas seminolipids have a 1-alkyl group.

“This finding is unique because SGalDAGs have never been characterized in detail in the testis,” Tamazawa said.

However, the precise mechanisms by which seminolipids contribute to spermatogenesis, and why the C16:0/C16:0 structure predominates, remain unknown.

The researchers suggest that understanding seminolipid function could inform new diagnostic or therapeutic strategies for male infertility, potentially leading to lipid supplements or biomarkers.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.