Milk through the millennia

Sixty-six million years ago, primitive animals with mammary glands managed to ride out a mass extinction event, with the eventual result that today humans have to pay bills and ponder our own mortality. However, we are the only mammals that can digest lactose into adulthood and blunt these pains with industrial quantities of cheddar cheese, so the verdict is out on whether this situation is a net positive or negative.

But for nearly two-thirds of adults worldwide who are lactose intolerant, milk, cheeses and other dairy products cause a different kind of pain. In the absence of lactase, the enzyme that cleaves lactose into glucose and galactose once the sugar enters our small intestines, lactose passes through whole and becomes food for the microbes that live in our large intestines. Their byproducts then cause bloating, nausea, stomach pains and diarrhea. Moreover, digesting the milk protein casein in adulthood releases insulin growth factor-1, a hormone that can, in excess, cause cystic acne. Production of lactase also can fall off suddenly in adulthood, although the role that diet — say, eating a brick of feta cheese every day for lunch for several months — may play in this is unclear.

The persistence of lactase in 35% of adults is due to single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene that codes for the enzyme. Several thousand years ago, the ability to continue digesting lactose was such a strong evolutionary advantage in pastoralist societies that alleles for it independently developed in human populations in both Northern Europe and Eastern Africa, with subgroups from the latter — in what are today Tanzania, Kenya and Sudan — developing three distinct polymorphisms.

Genetic analyses of modern pastoralists have helped revise our understanding of where lactase persistence developed, but they give a broad range— 6,800 to 2,700 years before the present day — for when those traits emerged.

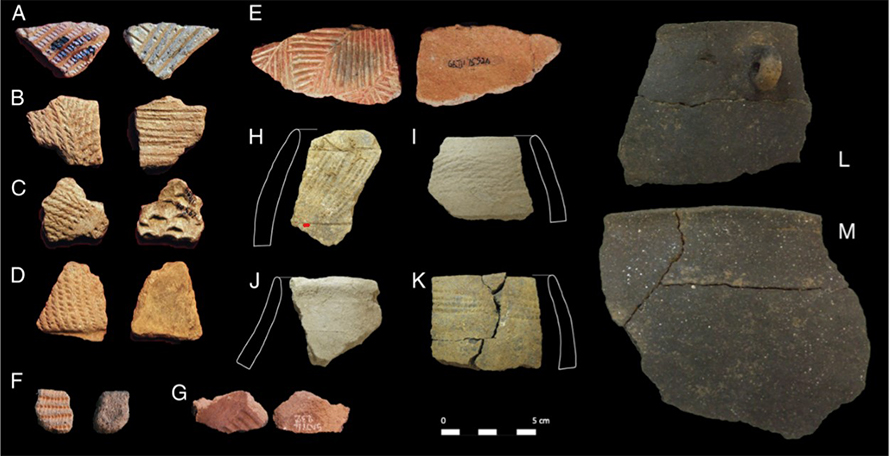

By analyzing the lipid residues on 125 fragments of ceramic pots recovered from sites in Kenya and Tanzania, scientists at the University of Bristol, the University of Florida and the University of Dar es Salaam have uncovered cultural contexts behind the genetic phenomenon that date its emergence in East Africa to approximately 5,000 years ago.

“Advances in ancient DNA recovery and processing have really helped us pinpoint when we think selection for these alleles appeared and evolved. We now know from the genetic record that this probably happened during a key time period known as the Pastoral Neolithic, which roughly dates to between 5,000 and 2,000 years ago in East Africa,” said Katherine Grillo, an anthropologist at the University of Florida. “But what we didn’t understand previously is the context in which selection for those alleles actually happened.”

Atomizing pottery

That context is provided by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Chromatography first was used to analyze residues in archaeological samples in 1976 when French scientists used gas chromatography to detect trace amounts of fatty acids — byproducts of oil — in fragments of jars used to transport goods in the ancient Mediterranean. Their work appeared in the journal Archaeometry.

Today, Julie Dunne, an analytical chemist at the University of Bristol uses GC–MS to examine the lipids embedded in the matrices of ancient shards of pottery.

“If you think about an unglazed ceramic pot, and if you had to put some milk in it, or even meat, and just boil it up, what you would actually see is fat globules floating on the top,” Dunne said. “Those globules of fat, lipids, absorb into the unglazed ceramic matrix during cooking.”

Unlike proteins, which are too large to fit in ceramic matrices, lipids are small, and can survive in the matrices of ceramic pots for more than 10,000 years.

“They sit very nicely in the pot until people like me come along and grind up broken potsherds, which are generally only what survives anyway,” Dunne said. “I’ve analyzed pottery from Europe and Africa which is nearly 10,000 years old, and there is actually pottery in Japan that goes back more like 15,000 to 17,000 years and has yielded lipids.”

In 2008, the leader of Dunne’s research group, Richard Evershed — who developed the field of organic residue analysis — helped determine that the earliest date that pastoral societies in Anatolia, now Turkey, began consuming processed dairy was 9,000 years ago. This predates the 5,000 year-old pottery that she and Grillo recently analyzed.

“If milk is being processed in the pots, we know humans are consuming milk,” Dunne said. “And once you start processing it and reduce the lactose content, then it makes it much easier for humans to digest. So that’s happening in the Near East around about 7000 B.C.”

From serendipity to eureka

in Nairobi, Kenya, studies the cultural impact of Kenya’s role in human

evolutionary research and the place of paleoanthropology in the broader world

of cultural anthropology.

The pottery sherds that Grillo and Dunne recently analyzed came from four sites across Kenya and Tanzania that are together representative of the breadth of Pastoral Neolithic sites in the region. While samples from the three sites located in Kenya — Dongodien, Jarigole and Ngamuriak — were obtained from museum collections in collaboration with Karega–Munene, an anthropologist at the United States International University in Nairobi, sherds from the fourth site were products of serendipity.

In 2012, Grillo and her colleagues had been searching for new archaeological sites in northern Tanzania when a collaborator, Agness O. Gidna from the National Museums of Tanzania in Dar Es Salaam, took a short trip home to her family’s farm near the town of Luxmanda on the Mbulu Plateau, farther south in north-central Tanzania.

“We had spent weeks and weeks surveying for new sites much farther north, and towards the end of a field season, Dr. Gidna said, ‘You know what? I’m just going to go home for a few days. I’ll be back,’ and she went. Then she calls us and she said, ‘there’s some pottery.’ And pretty soon realized we discovered that she had discovered the biggest Pastoral Neolithic site in East Africa,” Grillo said. “It’s in her mother’s yard.”

After the researchers recover a small, two- to three-centimeter sherd like those Gidna first found at the Luxmanda site, they clean its surface to remove the oils of more recent human lives — lotions, sunscreens and sebum — and pulverize the pottery into dust. They then use an acid extraction to separate the lipids from the sherds.

“Sometimes when we come to the end of the extraction, you can actually see the fat in the little vial coming from the animals cooked in the pots thousands of years ago, which is quite amazing,” Dunne said.

The scientists then run those lipids through a gas chromatograph, which lets them know whether the lipids are animal fats and whether they are too contaminated to be interpretable. The process most often yields fats from animals, but it also can reveal byproducts of plants and insects, such as bees, where lingering traces of wax will indicate that a population likely harvested honey. After then running the lipids through an isotope mass spectrometer, the researchers are able to differentiate whether they came from a ruminant — cattle, sheep or goats — or nonruminants, such as pigs, chickens and donkeys.

“Then we can also differentiate, most crucially, between milk and meat,” Dunne said. “And that was our eureka moment in our lab, probably 20 years ago now, that’s really enabled such a body of work on exploiting milk and the evolution of lactase persistence.”

By applying these techniques to the sherds from the four sites, Dunne, Grillo and their colleagues were able to obtain the first direct evidence that herders in ancient eastern Africa were consuming milk 5,000 years ago. Whether the gradual reduction in lactose content by fermentation ended up driving populations to consume more lactose-heavy, however, is a more elusive question.

“The development of widespread lactose persistence in herding societies through gene-culture coevolution is a topic now preoccupying scientists worldwide,” Grillo said. “Selection for lactase persistence may have become stronger as herders became even more specialized and dependent on livestock later on.”

Milk markets

Today, the reduction of lactose levels in processed dairy foods means someone who is lactose intolerant and no longer can eat softer cheeses like feta without first swallowing Lactaid might be able to eat a sharp block of cheddar that has almost all of its lactose removed.

According to Andrea S. Wiley, a medical anthropologist at the University of Indiana at Bloomington who studies the relationship between milk consumption and child health in the U.S. and in India, consumption of cheese, butter and similar products was the status quo of dairy production in the U.S. until the late 1800s.

“The late 19th century is really when milk consumption starts to become more common, other than just dairy products, and mostly as food for children as a breast milk substitute,” she said.

Over the ensuing decades, milk producers, working with the National Dairy Council, began pitching milk as a source of nutrients for children.

“The Dairy Council was formed in 1915, and that’s when they take the lead role in identifying what is the best food for children, and milk is a central part of that message,” Wiley said. “(They) tried out different nutrient messages, that milk is a good source of X, Y or Z. And the prevailing way, certainly beginning in the 1930s and on, was that milk has been understood nutritionally as a source of calcium. And that’s where the link to the strong bones matches up very nicely.”

That messaging stuck for decades. Take, for example, the “Got Milk?” ad campaign of the 1990s, which infiltrated billboards, magazines, airwaves, televisions and lunchrooms for more than 20 years to sell a generation and their parents on the belief that milk builds strong bones in children.While the link between cow’s milk and strong bones is dubious, the connection does have a scientific basis in breast milk: In infancy, breast milk acts as a source of calcium, and its whey and casein proteins act as growth promoters.

But a wildly successful ad campaign couldn’t reverse a downward trend that started after World War II, which marked the high point for American production and consumption of milk. The dairy industry today is in dire straits, with more than 2,700 dairy farms having gone out of business in the last two years and the amount of liquid milk consumed per capita plummeting more than 40% since 1975.

“We’re really back to where we were around the early 20th century in terms of milk consumption in the U.S.,” Wiley said. But despite the plummet in overall consumption of cow’s milk, she thinks milk as a substance still inspires a certain cultural reverence.

“Milk has always been positioned, I think, as a very special food. And, you know, in one way, it really is,” Wiley said. “Milk is what mammals produce, or female mammals produce, and it sustains infants when it’s all they consume.”

Lactase emergence

Over the past two decades, our understanding of lactose intolerance as an enzymatic matter also has been transformed and revised, according to Sarah Tishkoff, a geneticist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine who studies genetic variation in East African populations.

In 2002, the geneticist Leena Peltonen and her colleagues created a map of genetic variants in Finnish families that were lactose intolerant, a rarity in Northern Europe. This discovery was essential to understanding the genetic mechanisms of lactase persistence.

“They thought of lactose intolerance like a disease, basically,” Tishkoff said. “It was interesting because (the mutations) were not in the lactase gene, they were upstream in front of a neighboring gene. And at that time, very little was known about gene regulation. It was a rare example of finding a regulatory mutation that influences this well-known common trait.”

Four years later, Tishkoff and her colleagues, working with Tanzanian, Kenyan and Sudanese ethnic groups, found that lactase persistence evolved at least four times in human populations. They described this convergent evolution of lactase persistence in the journal Nature and expanded upon it in 2014 in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

“We saw this very strong genomic footprint of selection,” Tishkoff said. “And that was one of the earliest genomic signatures of selection, and still one of the strongest signals in the human genome.”

Lipid whispers

Today, pastoralist societies in Eastern Africa still rely on milk and milk products from cattle, sheep, goats or camels; some groups are estimated to derive up to 60% or even 90% of their total calories from milk products, which they complement with meat, maize, beans and seasonally available plants.

While the digestive chemistry of humans has changed over the past 10,000 years, the enzymatic activity of bovine stomachs has not, making modern cows proxies for the ancient cattle of pastoralists past. A plant that passes through a cow’s stomach in significant quantities today will make the same subtle imprint on the chromatographic character of its milk that its identical ancestor did millennia ago.

This has yielded insights that cattle and assorted mammals in ancient Europe tended to eat very temperate vegetation known as C3 plants, named after the number of carbon molecules in the first compound formed by the Calvin cycle of carbon fixation, but African mammals tended to eat more arid-friendly C4 plants like sorghum and amaranths.

“We see, for example, the animals were eating lots of C4 grasses, and so we think in East Africa at this time, there were some environmental shifts happening,” Grillo said. “Even if people weren’t able to be farmers because of unpredictable or patchy rainfall, they may have had milk or something like it.”

By providing glimpses into past periods of climate and habitat disruption, forces that will continue to shape the lives of pastoralists in coming decades, Grillo hopes the long-preserved lipids may make the case for a more resilient lifestyle.

“It’s getting harder to be a herder in many areas (that are) drying out, but it’s actually much easier to be a herder when the climate is getting really unpredictable and arid than it is to be a farmer,” Grillo said. “We can build a much more holistic picture of what life was like for these people because of the residue analysis.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.