From CRISPR to glowing proteins to optogenetics

Today big, game-changing ideas are less common. New and improved techniques are the driving force behind modern scientific research and discoveries. They allow scientists — including chemists like me — to do our experiments faster than before, and they shine light on areas of science hidden to our predecessors.

array of studies.

Three cutting-edge techniques — the gene-editing tool CRISPR, fluorescent proteins and optogenetics — were all inspired by nature. Biomolecular tools that have worked for bacteria, jellyfish and algae for millions of years are now being used in medicine and biological research. Directly or indirectly, they will change the lives of everyday people.

Bacterial defense systems as genetic editors

Bacteria and viruses battle themselves and one another. They are at constant biochemical war, competing for scarce resources.

One of the weapons that bacteria have in their arsenal is the CRISPR–Cas system. It is a genetic library consisting of short repeats of DNA gathered over time from hostile viruses, paired with a protein called Cas that can cut viral DNA as if with scissors. In the natural world, when bacteria are attacked by viruses whose DNA has been stored in the CRISPR archive, the CRISPR-Cas system hunts down, cuts and destroys the viral DNA.

Scientists have repurposed these weapons for their own use, with groundbreaking effect. Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist based at the University of California, Berkeley, and French microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier shared the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of CRISPR-Cas as a gene-editing technique.

The Human Genome Project has provided a nearly complete genetic sequence for humans and given scientists a template to sequence all other organisms. However, before CRISPR–Cas, we researchers didn’t have the tools to easily access and edit the genes in living organisms. Today, thanks to CRISPR-Cas, lab work that used to take months and years and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars can be done in less than a week for just a few hundred dollars.

There are more than 10,000 genetic disorders caused by mutations that occur on only one gene, the so-called single-gene disorders. They affect millions of people. Sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis and Huntington’s disease are among the most well-known of these disorders. These are all obvious targets for CRISPR therapy because it is much simpler to fix or replace just one defective gene rather than needing to correct errors on multiple genes.

For example, in preclinical studies, researchers injected an encapsuled CRISPR system into patients born with a rare genetic disease, transthyretin amyloidosis, that causes fatal nerve and heart conditions. Preliminary results from the study demonstrated that CRISPR–Cas can be injected directly into patients in such a way that it can find and edit the faulty genes associated with a disease. In the six patients included in this landmark work, the encapsuled CRISPR–Cas minimissiles reached their target genes and did their job, causing a significant drop in a misfolded protein associated with the disease.

Jellyfish light up the microscopic world

The crystal jellyfish, Aequorea victoria, which drifts aimlessly in the northern Pacific, has no brain, no anus and no poisonous stingers. It is an unlikely candidate to ignite a revolution in biotechnology. Yet on the periphery of its umbrella, it has about 300 photo-organs that give off pinpricks of green light that have changed the way science is conducted.

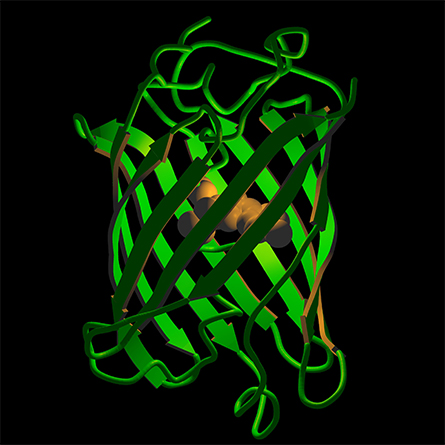

This bioluminescent light in the jellyfish stems from a luminescent protein called aequorin and a fluorescent molecule called green fluorescent protein, or GFP. In modern biotechnology GFP acts as a molecular lightbulb that can be fused to other proteins, allowing researchers to track them and to see when and where proteins are being made in the cells of living organisms. Fluorescent protein technology is used in thousands of labs every day and has resulted in the awarding of two Nobel Prizes, one in 2008 and the other in 2014. And fluorescent proteins have now been found in many more species.

in Chemistry for their groundbreaking work on green fluorescent protein.

This technology proved its utility once again when researchers created genetically modified COVID-19 viruses that express GFP. The resulting fluorescence makes it possible to follow the path of the viruses as they enter the respiratory system and bind to surface cells with hairlike structures.

Algae let us play the brain neuron by neuron

When algae, which depend on sunlight for growth, are placed in a large aquarium in a darkened room, they swim around aimlessly. But if a lamp is turned on, the algae will swim toward the light. The single-celled flagellates — so named for the whiplike appendages they use to move around — don’t have eyes. Instead, they have a structure called an eyespot that distinguishes between light and darkness. The eyespot is studded with light-sensitive proteins called channelrhodopsins.

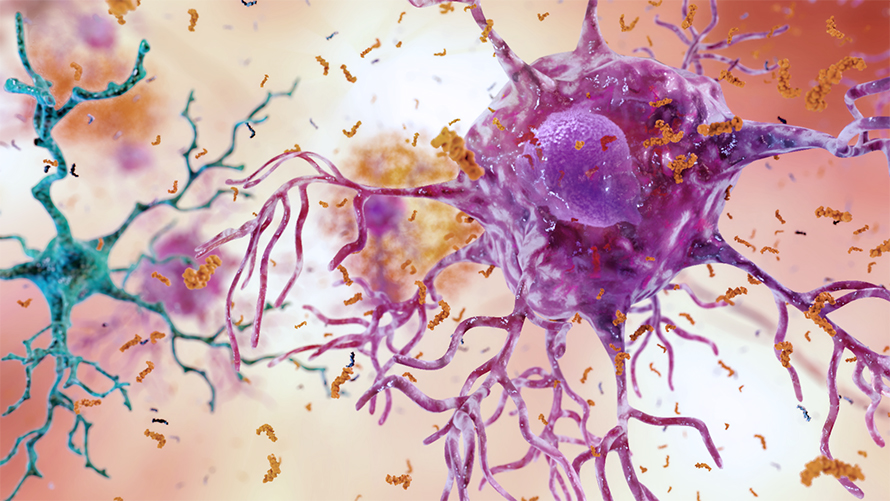

In the early 2000s, researchers discovered that when they genetically inserted these channelrhodopsins into the nerve cells of any organism, illuminating the channelrhodopsins with blue light caused neurons to fire. This technique, known as optogenetics, involves inserting the algae gene that makes channelrhodopsin into neurons. When a pinpoint beam of blue light is shined on these neurons, the channelrhodopsins open up, calcium ions flood through the neurons and the neurons fire.

Using this tool, scientists can stimulate groups of neurons selectively and repeatedly, thereby gaining a more precise understanding of which neurons to target to treat specific disorders and diseases. Optogenetics might hold the key to treating debilitating and deadly brain diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

But optogenetics isn’t only useful for understanding the brain. Researchers have used optogenetic techniques to partially reverse blindness and have found promising results in clinical trials using optogenetics on patients with retinitis pigmentosa, a group of genetic disorders that break down retinal cells. And in mouse studies, the technique has been used to manipulate heartbeat and regulate bowel movements of constipated mice.

What else lies within nature’s toolbox?

What undiscovered techniques does nature still hold for us?

According to a 2018 study, people represent just 0.01% of all living things by mass but have caused the loss of 83% of all wild mammals and half of all plants in our brief time on Earth. By annihilating nature, humankind might be losing out on new, powerful and life-altering techniques without having even imagined them.

After all, no one could have foreseen that the discovery of three groundbreaking processes derived from nature could change the way science is done.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.