JBC: Starving triple-negative breast cancer slows growth

A team of Brazilian researchers has developed a strategy that slows the growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells by cutting them off from two major food sources.

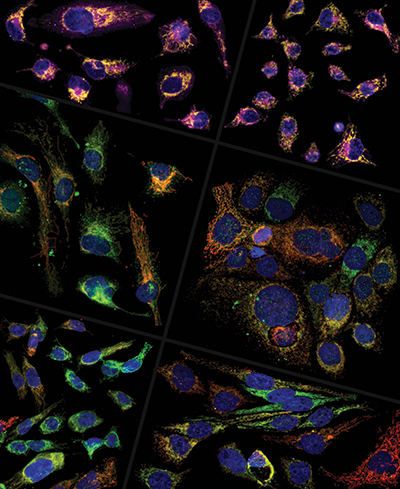

Heterogeneous presentation of glutaminase (red) and CPT1 (green) is shown across several TNBC cell lines. The cell line in the top right panel is resistant to the drug CB-839. A study by dos Reis et al. suggests that these cells survive treatment by increasing fatty acid (purple) consumption in their mitochondria (yellow). Douglas Adamoski/Brazilian Biosciences National Laboratory

Heterogeneous presentation of glutaminase (red) and CPT1 (green) is shown across several TNBC cell lines. The cell line in the top right panel is resistant to the drug CB-839. A study by dos Reis et al. suggests that these cells survive treatment by increasing fatty acid (purple) consumption in their mitochondria (yellow). Douglas Adamoski/Brazilian Biosciences National Laboratory

About 15% to 20% of all breast cancers are triple-negative, and the type is most common in African American women. These tumors lack estrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2 protein that are present in other breast cancers and permit certain targeted therapies. Every TNBC tumor has a different genetic makeup, so finding new markers to guide treatment has been difficult.

Sandra Martha Gomes Dias is a cancer researcher at the Brazilian Biosciences National Laboratory in Campinas, Brazil. “There is intense interest in finding new medications that can treat this kind of breast cancer,” she said. “TNBC is considered to be more aggressive and have a poorer prognosis than other types of breast cancer, mainly because there are fewer targeted medicines that treat TNBC.”

In a new study in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Dias and colleagues demonstrate that in addition to glutamine, a well-known cancer food source, TNBC cells can use fatty acids to grow and survive. When inhibitors that block both glutamine and fatty acid metabolism were used in concert, Dias said, TNBC growth and migration slowed.

To maintain their ability to grow at a breakneck pace, cancer cells often consume nutrients at a higher rate than normal cells. Glutamine, the most abundant amino acid in plasma, is one of these nutrients. Some cancers become heavily reliant on this versatile molecule, Dias said, as it offers energy, carbon, nitrogen and antioxidant properties, all of which support tumor growth and survival.

The drug telaglenastat, also known as CB-839, prevents glutamine processing and is in clinical trials to treat TNBC and other tumor types. CB-839 deactivates the enzyme glutaminase, preventing cancer cells from breaking down and reaping the benefits of glutamine. However, recent research has shown that some TNBC cells can resist its effects.

To see if alterations in gene expression could explain how these cells survive, Dias said, her team exposed TNBC cells to CB-839 and then defined those that were resistant and those that were sensitive to the drug and sequenced their RNA.

In the resistant cells, molecular pathways related to the processing of lipids were altered, Dias said. In particular, levels of the enzymes CPT1 and CPT2, critical for fatty acid metabolism, were increased.

“CPT1 and 2 act as gateways for the entrance of fatty acids into mitochondria, where they will be used as fuel for energy production,” Dias said. “Our hypothesis was that closing this gateway by inhibiting CPT1 in combination with glutaminase inhibition would decrease growth and migration of CB-839-resistant TNBC cells.”

The double inhibition slowed proliferation and migration in resistant TNBC cells more than individual inhibition of either CPT1 or glutaminase. Dias said these results provide new genetic markers to better guide drug choice in patients with TNBC.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Fasting, fat and the molecular switches that keep us alive

Nutritional biochemist and JLR AE Sander Kersten has spent decades uncovering how the body adapts to fasting. His discoveries on lipid metabolism and gene regulation reveal how our ancient survival mechanisms may hold keys to modern metabolic health.