JBC: Outfitting T cell receptors for special combat

Researchers have engineered antibodylike T cell receptors that stick to cells infected with cytomegalovirus, or CMV, which can be deadly for patients with weakened immune systems. These receptors potentially could be used to monitor or destroy the virus and might also be able to target brain tumors.

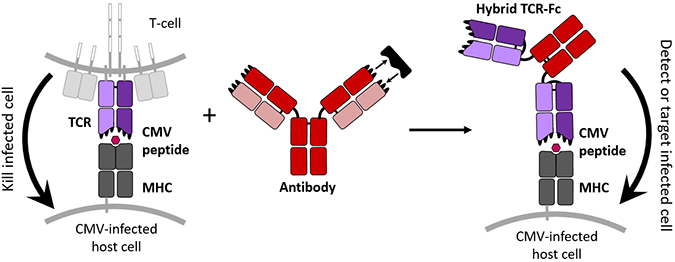

CMV causes lifelong infection in more than half of all adults by age 40, but the virus lies dormant in most. T cells normally circulate through the body and use their membrane-bound T cell receptors, or TCRs, to detect disease-associated proteins hiding inside infected cells. TCRs then can instruct T cells to destroy the infection. For immunocompromised patients, however, this defense mechanism is diminished, leaving them vulnerable to the virus.

Researchers have used T cells to treat disease before, but engineering and transplanting whole T cells is costly and invasive. In a study published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, a team of researchers took an alternative approach, producing CMV-detecting TCRs that float freely in the body and bind tightly to their diseased targets.

“Right now, we’ve got a molecule that looks like an antibody but it binds to a (CMV-associated) peptide that would normally be recognized by a TCR,” said Jennifer Maynard, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Texas at Austin and senior author of the study. “Antibodies cannot normally access these molecules, so that’s a big deal.”

Researchers frequently use bacterial or yeast cells as miniature biomolecule factories, but their nonmammalian molecular machinery often introduces defects in human TCRs, Maynard said. To provide a more suitable environment, the authors used hamster ovary cells to produce the receptors.

This new hybrid protein combines the cell targeting properties of a TCR with the tight binding and free-floating nature of an antibody to create a new molecule able to tag CMV-infected cells specifically. jennifer maynard, ellen wagner/university of texasTCRs naturally bond loosely with their targets, but the authors wanted theirs to bind and not let go. To strengthen these connections, the authors randomly mutated the DNA of the TCR component that detects the CMV peptide. They inserted many versions of the mutated DNA into the hamster cells, which then manufactured about a million types of TCR, Maynard said.

This new hybrid protein combines the cell targeting properties of a TCR with the tight binding and free-floating nature of an antibody to create a new molecule able to tag CMV-infected cells specifically. jennifer maynard, ellen wagner/university of texasTCRs naturally bond loosely with their targets, but the authors wanted theirs to bind and not let go. To strengthen these connections, the authors randomly mutated the DNA of the TCR component that detects the CMV peptide. They inserted many versions of the mutated DNA into the hamster cells, which then manufactured about a million types of TCR, Maynard said.

The researchers measured bonding strength by exposing those myriad TCR variations to the CMV peptide.

“We found one that was our favorite,” Maynard said. “We improved the binding affinity 50-fold.”

To liberate the TCRs from the T cell membrane, the researchers further edited the DNA so the TCRs would attach to the protein stem of Y-shaped antibodies. And to help these proteins hold their shape, they added a bond inside the TCR and prevented sugars from attaching.

These new TCRs could track disease progression in patients or evaluate new vaccines. They also might restore immune response in patients by instructing their cells to attack CMV infections, Maynard said.

This new molecule could be effective in treating glioblastoma as well. Although these brain tumors do not produce many distinct markers, they do suppress the immune system, which in CMV-infected patients can bring the virus back to life in tumors, Maynard said.

“Our protein could be used to specifically target glioblastoma cells, and it would provide a very unique marker,” Maynard said. “We would use this to monitor or kill some of those tumor cells.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.