Researchers create a effective RNA vaccine for malaria

Malaria remains a significant problem facing Africa. Of the 409,000 worldwide malaria deaths estimated by the WHO in 2019, 94 percent of all cases occurred in Africa.

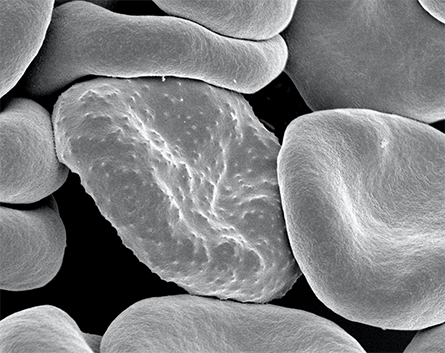

Malaria is caused by a parasite, carried and transmitted to humans by female Anopheles mosquitoes (there are more than 400 species of this particular type of mosquito, and 30 of them can carry malaria). The battle between malaria and science remains because of a handy trick this parasite plays on the immune system.

Our immune system has a component called "MIF" which stands for "cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor." The job of MIF is to regulate the movement of immune cells to the site of an infection (either attracting them to the site, or stopping them from continuing to arrive once the invader or injury is gone). Plasmodium, the one-celled parasite that causes malaria, can produce a nonfunctional "decoy" of MIF, causing our confused immune system to then fail to make the T cells that would normally be stimulated as a result of regular MIF activity during infection. The ultimate result is no production of T cells, which would normally make memory B cells that would generate long-lasting immunity against the malaria.

Now you might be able to see why designing a vaccine is challenging for malaria. In a typical vaccine, a bit of protein or a deactivated virus or bacteria is used to stimulate the immune system. Your immune system then pumps out antibodies against that invader, and you're left with memory B cells that remember that infection; the body is then primed and ready to fight a future infection. The Plasmodium parasite interferes with the process of T cells leading to those long-lived memory B cells that would fight off future infections faster and more efficiently. So, your next encounter with this parasite would be the same as your first, with no built-up immunity

malaria in humans. During its development, the parasite forms protrusions

called 'knobs' on the surface of its host red blood cell which enable

it to avoid destruction and cause inflammation

Thankfully, there is hope. Yale researchers recently filed a patent for a malaria vaccine using a RNA platform. mRNA vaccines are a relatively new technology that uses non-infectious and non-integrating (this means it won't accidentally become part of your healthy cells) piece of genetic material from the pathogen of interest (in our case, malaria).

mRNA is kind of like instructions for generating a protein. By delivering the mRNA as a vaccine, your body takes the genetic material up into cellular cytoplasm (the liquid inside of your cells), and begin to make the protein by following instructions within the mRNA. This new protein is then released, spotted by your vigilant immune system, and flagged. As your body becomes aware of the threat, your T cells and immune system are activated, and memory B cells are formed against the pathogen. Just like that — you're immune!

For now, mosquito nets remain the best (and often only) preventative measure

against this deadly disease

This new vaccine, generated by Richard Bucala and Andrew Geall is an saRNA (similar to mRNA, but more efficient) vaccine that encodes the PMIF that Plasmodium normally uses to disarm our immune system. As Bucala and Geall discovered, immunizing patients with saRNA that encodes PMIF uses the parasite's own gene against it, and confers protection. These results were also seen in a study from 2018, in which MIF was tested successfully used as a treatment for malaria infection in a mouse model.

Malaria and COVID-19 have two thin in common. Both are serious problems continuing to cause high caseloads and fatality rates globally. Both have had mRNA-based vaccines suggested as their solution (malaria is an experimental vaccine, COVID-19 mRNA vaccines have now been approved and are in use). Researchers continue to test mRNA vaccine candidates for a variety of diseases in the hopes that more solutions to deadly pathogens will be found.

Bucala and Geall's new malaria vaccine candidate is a great example of a new technology being applied to a previously unsolvable problem. This is what science is all about. mRNA vaccines have been applied to a number of problematic pathogens including COVID-19, rabies, Zika virus. Perhaps the most famous mRNA vaccines are the ones developed in the last year to target the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19. The Pfizer Inc and BioNTech vaccine (almost 94 million doses have been administered in the US alone in recent months) is an mRNA vaccine, as is the Moderna vaccine, which is ramping up production and distribution. Researchers and doctors alike continue to hope that this technology will help us see the end of the most significant global outbreak in recent history.

This story originally appeared on Massive Science, an editorial partner site that publishes science stories by scientists. Subscribe to their newsletter to get even more science sent straight to you.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.