Study sheds light on treatment for rare genetic disorder

A new study from researchers in the University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Biochemistry reveals key insights into how a therapeutic drug tackles a deadly genetic disease and opens doors to additional research. Their findings are published in Nature Communications.

Until recently, babies born with the most severe forms of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) rarely survived past early childhood. The disorder, while rare, is the most common genetic cause of death in infants.

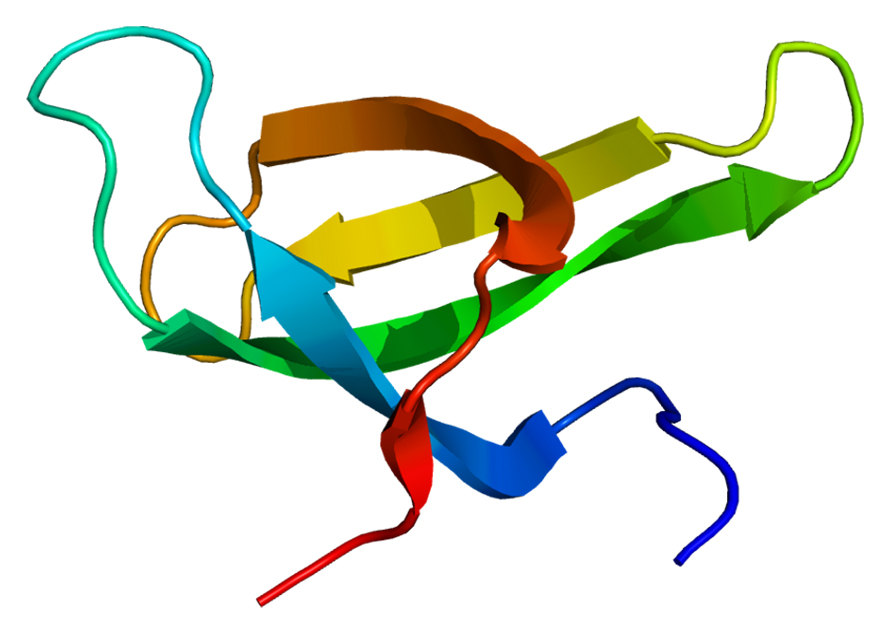

SMA results from errors in production of the survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein. SMA affects nerve cells responsible for voluntary muscle movement, including respiratory muscles, causing the muscles to shrivel and become inactive.

Relatively new drugs such as branaplam, nusinersen (Spinraza), and risdiplam (Ecrysdi) are giving hope to children born with SMA. Some children with SMA and treated with nusinersen (the first FDA approved SMA treatment, which acts by binding to a region of the survival of motor neuron RNA) are now approaching adolescence. Risdiplam and branaplam, which have also been studied for treating SMA, change how the cell cuts and pastes the RNA — part of a process known as splicing — so it can make a functional SMN protein.

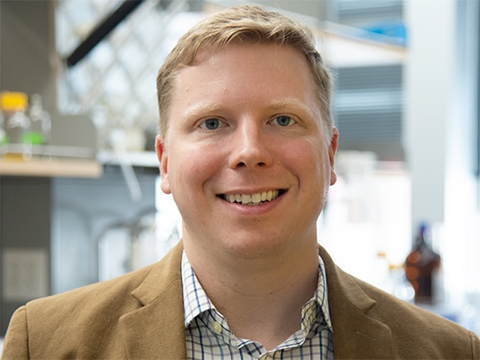

“Risdiplam and branaplam represent fairly new types of medical therapies directed to act on RNA,” explains Aaron Hoskins, a professor in the UW–Madison Department of Biochemistry who specializes in RNA splicing and the factors at play when splicing goes awry. “They’re able to change RNA processing at very particular sites and in very defined ways. This wouldn’t have been possible 15 years ago, so there are kids alive today who could never have survived before.”

Branaplam was developed to interact with RNA’s nucleic acid building blocks. But despite the drug’s life-saving capabilities, exactly how branaplam and related drugs address errors in RNA splicing has eluded researchers. The RNAs and factors involved in splicing are complex and difficult to study.

Hoskins partnered with Remix Therapeutics, a pharmaceutical company that develops RNA-targeting drugs such as branaplam, to study branaplam’s impact on RNA splicing. “A major focus of my lab has been understanding splice site recognition — the exact step where these therapies work. Remix and my lab had highly complementary approaches to science, so it was natural for us to work together on this,” says Hoskins, who is also a member of the scientific advisory board at Remix Therapeutics.

In their recent study, Hoskins and David White (a former member of the Hoskins Lab) worked alongside Bryan Dunyak and Fred Vaillancourt, scientists at Remix. They discovered that branaplam does not, as previously believed, directly target RNA. Instead, the drug targets a complex made of both RNA and protein. In the absence of that protein, the drug only weakly associates with RNA, likely explaining the results of earlier research.

In the short time since their discovery, results have already opened new possibilities for further study and drug development of branaplam and related therapeutics. The team is continuing to work on understanding how these drugs are able to target specific sites, such as the SMN gene, rather than randomly effecting RNA splicing.

Hoskins hopes that this research will pave the way for new, increasingly effective therapeutics to treat SMA and other illnesses such as Huntington’s disease, which could also be treated with RNA-targeting drugs. “I imagine we’ll be applying this to other new molecules and drug candidates. The available drugs are limited now, but this industry-academic collaboration is a step towards finding more therapeutic options for people with deadly genetic diseases.”

This article is republished from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Biochemistry News. Read the original here.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.