From the journals: JLR

Why is a high level of HDL cholesterol not always a good thing? How does gut bacteria assimilate dietary lipids? How can researchers measure pleiotropic genetic risk factors? Read about recent papers in the Journal of Lipid Research that address these questions.

Why high HDL is not always good

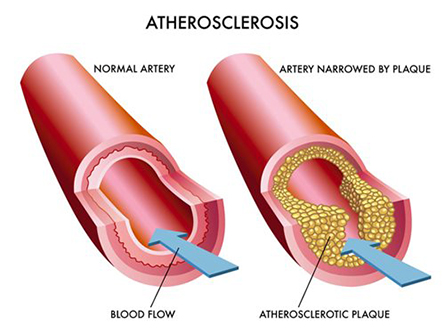

Heart diseases are the leading cause of death in the U.S. Coronary heart disorder, the most common type of heart disease, is caused by atherosclerosis, or the accumulation of cholesterol in the arterial walls leading to stiffening and lowered blood flow in the arteries. The two types of cholesterol are low-density lipoprotein, or LDL, and high-density lipoprotein, or HDL. While HDL cholesterol often is referred to as "good cholesterol" because of the inverse correlation between HDL levels and heart disorders, presence of excess HDL in plasma may be due to reduced plasma clearance of cholesterol.

The primary receptor for HDL is scavenger receptor class B type I, or SR-BI, which promotes clearance of excess cholesterol from the plasma, thus reducing the risk for atherosclerosis.

In a recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research, Sarah C. May and her colleagues at the Medical College of Wisconsin characterized a rare heterozygous variant of the gene encoding SR-BI that results in the substitution of arginine-174 with cysteine, or R174C, in a patient with high HDL cholesterol levels. They demonstrated that the R174C mutation leads to diminished cholesterol transport, suggesting this variant does not clear cholesterol from circulation as intended.The researchers write that the reduced function of this variant could be due to disruptions in surface electrostatic charges of SR-BI leading to a decrease in the net-positive charge, which in turn could affect the ability of SR-BI to bind HDL and transport cholesterol from HDL particles.

This study provides an insight into the structure and function of SR-BI and emphasizes that measurement of HDL-cholesterol levels may not be a sufficient indicator to predict the risk of cardiovascular diseases accurately.

How gut bacteria assimilate dietary lipids

The human intestine is home to trillions of microorganisms known collectively as the gut microbiota. The type and amount of fat we eat can have a significant impact on the gut microbiome and thus on our metabolism and immunity. Sphingolipids are a class of bioactive lipids present in foods such as milk and also produced by gut microbes. However, researchers do not understand yet how the gut microbes use sphingolipids.

Recent research by Min-Ting Lee and colleagues at Cornell University published in the Journal of Lipid Research used a novel technique called Bioorthogonal labeling-Sort-Seq-Spec, or BOSSS, to study the assimilation of sphingolipids by gut microbes. The first step in BOSSS, bioorthogonal labeling of sphingolipids, involved labeling without interfering with native biochemical processes in the body. The next step was fluorescence-based sorting of microbes containing the labeled sphingolipids. Finally, the sorted microbes were sequenced and analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify products of sphingolipid assimilation.

The researchers found that sphingolipids are assimilated primarily by a type of gut microbes known as Bacteriodes. This improves our understanding of how dietary sphinganine is processed in the body and how it in turn affects the gut microbiome. In addition, the novel BOSSS technique is useful to study the flux of any alkyne-labeled metabolite in diet–microbiome interactions.

A randomization to measure risk

Variations in certain genes can act as risk factors for some diseases, and these risk associations can be studied using a technique called Mendelian randomization, or MR. This technique measures variations in genes whose functions are known in order to determine whether the variations can cause specific diseases in humans.In a recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research, David G. Thomas and colleagues at Columbia University performed an MR of lipid traits such as levels of low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, body mass index, Type 2 diabetes and systolic blood pressure in coronary artery disease, or CAD, in large genomewide association study data sets.

A challenging aspect of determining the effect of risk factors is that some of these lipid trait variants may be pleiotropic, meaning that a single gene can influence two or more seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits. This study used multivariate MR analysis to evaluate the pleiotropic effects of lipid trait genetic variants and to adjust for these effects in evaluating the risk for CAD. The researchers reported that the lipid traits they studied all are associated independently with CAD even after adjusting for their pleiotropic effects.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.