Astrocyte cells in the fruit fly brain are an on-off switch

Neuroplasticity — the ability of neurons to change their structure and function in response to experiences — can be turned off and on by the cells that surround neurons in the brain, according to a new study on fruit flies that I co-authored.

and the cells that surround them in the brain.

As fruit fly larvae age, their neurons shift from a highly adaptable state to a stable state and lose their ability to change. During this process, support cells in the brain – called astrocytes — envelop the parts of the neurons that send and receive electrical information. When my team removed the astrocytes, the neurons in the fruit fly larvae remained plastic longer, hinting that somehow astrocytes suppress a neuron's ability to change. We then discovered two specific proteins that regulate neuroplasticity.

Why it matters

The human brain is made up of billions of neurons that form complex connections with one another. Flexibility at these connections is a major driver of learning and memory, but things can go wrong if it isn't tightly regulated. For example, in people, too much plasticity at the wrong time is linked to brain disorders such as epilepsy and Alzheimer's disease. Additionally, reduced levels of the two neuroplasticity-controlling proteins we identified are linked to increased susceptibility to autism and schizophrenia.

Similarly, in our fruit flies, removing the cellular brakes on plasticity permanently impaired their crawling behavior. While fruit flies are of course different from humans, their brains work in very similar ways to the human brain and can offer valuable insight.

One obvious benefit of discovering the effect of these proteins is the potential to treat some neurological diseases. But since a neuron's flexibility is closely tied to learning and memory, in theory, researchers might be able to boost plasticity in a controlled way to enhance cognition in adults. This could, for example, allow people to more easily learn a new language or musical instrument.

How we did the work

My colleagues and I focused our experiments on a specific type of neurons called motor neurons. These control movements like crawling and flying in fruit flies. To figure out how astrocytes controlled neuroplasticity, we used genetic tools to turn off specific proteins in the astrocytes one by one and then measured the effect on motor neuron structure. We found that astrocytes and motor neurons communicate with one another using a specific pair of proteins called neuroligins and neurexins. These proteins essentially function as an off button for motor neuron plasticity.

What still isn't known

My team discovered that two proteins can control neuroplasticity, but we don't know how these cues from astrocytes cause neurons to lose their ability to change.

Additionally, researchers still know very little about why neuroplasticity is so strong in younger animals and relatively weak in adulthood. In our study, we showed that prolonging plasticity beyond development can sometimes be harmful to behavior, but we don't yet know why that is, either.

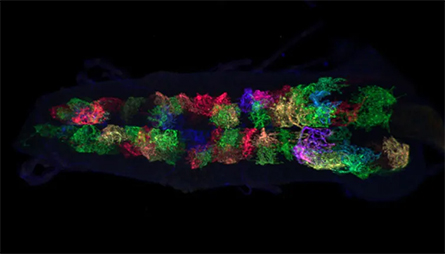

and the attached nerve cord on the left, the astrocytes are labeled in different

colors showing their wide distribution among neurons.

What's next

I want to explore why longer periods of neuroplasticity can be harmful. Fruit flies are great study organisms for this research because it is very easy to modify the neural connections in their brains. In my team's next project, we hope to determine how changes in neuroplasticity during development can lead to long–term changes in behavior.

There is so much more work to be done, but our research is a first step toward treatments that use astrocytes to influence how neurons change in the mature brain. If researchers can understand the basic mechanisms that control neuroplasticity, they will be one step closer to developing therapies to treat a variety of neurological disorders.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.