Protein that can be toxic in heart and nerves may help prevent Alzheimer's

A protein that wreaks havoc in the nerves and heart when it clumps together can prevent the formation of toxic protein clumps associated with Alzheimer's disease, a new study led by a University of Texas Southwestern researcher shows. The findings, published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, could lead to new treatments for this brain-ravaging condition, which currently has no truly effective therapies and no cure.

Researchers long have known that sticky plaques of a protein known as amyloid beta are a hallmark of Alzheimer's and are toxic to brain cells. As early as the mid-1990s, other proteins were discovered in these plaques as well.

One of these, a protein known as transthyretin, or TTR, seemed to play a protective role, explained Lorena Saelices, assistant professor of biophysics at the Center for Alzheimer's and Neurodegenerative Diseases at UTSW, a center that is part of the Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute. When mice modeled to have Alzheimer's disease were genetically altered to make more TTR, they were slower to develop an Alzheimer's-like condition; when they made less TTR, they developed the condition faster.

way discovered by UTSW researchers to stop this process, leveraging the protective nature of the protein transthyretin (TTR) to identify a segment

of this protein, TTR-S, that halts plaque formation and facilitates its degradation in a test tube.

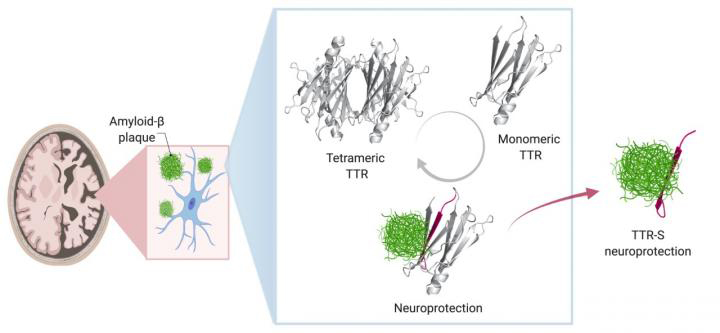

In healthy people and animals, Saelices said, TTR helps transport thyroid hormone and the vitamin A derivative retinol to where they're needed in the body. For this job, TTR forms a tetramer — a shape akin to a clover with four identical leaflets. However, when it separates into molecules called monomers, these individual pieces can act like amyloid beta, forming sticky fibrils that join together into toxic clumps in the heart and nerves to cause the rare disease amyloidosis. In this condition, amyloid protein builds up in organs and interferes with their function.

Saelices wondered whether there might be a connection between TTR's separate roles in both preventing and causing amyloid-related diseases. "It seemed like such a coincidence that TTR had such opposing functions," she said. "How could it be both protective and damaging?"

To explore this question, she and her colleagues developed nine different TTR variants with differing propensities to separate into monomers that aggregate, forming sticky fibrils. Some did this quickly, over the course of hours, while others were slow. Still others were extremely stable and didn't dissociate into monomers at all.

When the researchers mixed these TTR variants with amyloid beta and placed them on neuronal cells, they found stark differences in how toxic the amyloid beta remained. The variants that separated into monomers and aggregated quickly into fibrils provided some protection from amyloid beta, but it was short-lived. Those that separated into monomers but took longer to aggregate provided significantly longer protection. And those that never separated provided no protection from amyloid beta at all.

Saelices and her colleagues suspected that part of TTR was binding to amyloid beta, preventing amyloid beta from forming its own aggregations. However, that important piece of TTR seemed to be hidden when this protein was in its tetramer form. Sure enough, computational studies showed that a piece of this protein that was concealed when the leaflets were conjoined could stick to amyloid beta. However, this piece tended to stick to itself to quickly form clumps. After modifying this piece with chemical tags to halt self-association, the researchers created peptides that could prevent the formation of toxic amyloid beta clumps in solution and even break apart preformed amyloid beta plaques. The interaction of modified TTR peptides with amyloid beta resulted in the conversion to forms called amorphous aggregates that were broken up easily by enzymes. In addition, the modified peptides prevented amyloid seeding, a process in which fibrils of amyloid beta extracted from Alzheimer's disease patients can act as a template in the formation of new fibrils.

Saelices and her colleagues are currently testing whether this modified TTR peptide can prevent or slow progression of Alzheimer's in mouse models. If they're successful, she said, this protein snippet could form the basis of a new treatment for this recalcitrant condition.

"By solving the mystery of TTR's dual roles," she said, "we may be able to offer hope to patients with Alzheimer's."

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.