New tool can assist with identifying carbohydrate-binding proteins

One of the major obstacles that those conducting research on carbohydrates are constantly working to overcome is the limited array of tools available to decipher the role of sugars. As a workaround, most researchers utilize lectins (sugar-binding proteins) isolated from plants or fungi, but they are large, with weak binding, and they are limited in their specificity and in the scope of sugars that they detect. In a new study published in ACS Chemical Biology, researchers in Barbara Imperiali's group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have developed a platform to address this shortcoming.

“The challenge with polymers of carbohydrates is that their biosynthesis is not template-driven,” said Imperiali. “Biology, medicine, and biotechnology have been fueled by technological advancements for proteins and nucleic acids. The carbohydrate field lags terribly behind and is desperately seeking tools.”

Identifying carbohydrate-binding proteins

Biosynthesizing carbohydrates requires every link between individual sugar molecules to be made by a particular enzyme, and there’s no ready way to decipher the structures and sequences of complex carbohydrates. Antibodies to carbohydrates can be generated, but doing so is challenging, expensive, and results in a molecule that is far larger than what is really needed for the research. An ideal resource for this field plagued with limited mechanisms would be discovery of binding proteins, of limited size, that recognize small chunks of carbohydrates to piece together a structure by using those binders, or methodsto detect and identify particular carbohydrates within complicated structures.

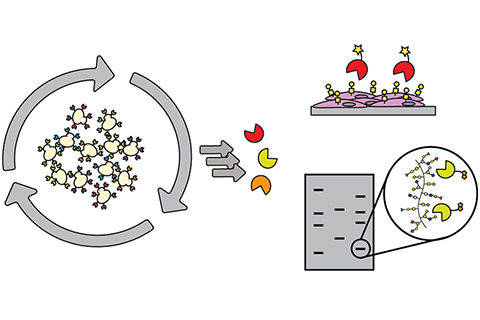

The authors of this study used directed evolution and clever screen design to identify carbohydrate-binding proteins from proteins that have absolutely no ability to bind carbohydrates at all. Their findings lay the groundwork for identifying carbohydrate-binding proteins with diverse and programmable specificity.

Streamlining for collaboration

This advance will allow researchers to go after a user-defined sugar target without being limited by what a lectin does, or challenged by the abilities of generating antibodies. These results could serve to inspire future collaborations with engineering communities to maximize the efficiency of glycobiology’s yeast surface display pipeline. As it is, this pipeline works well for proteins, but sugars are far more difficult targets and require the pipeline to be modified.

In terms of future applications, the potential for this innovation ranges from diagnostic to, in the longer term, therapeutic, and paves the way for collaborations with researchers at MIT and beyond. For example, chemistry Professor Laura Kiessling's research group works with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), which has an unusual cell wall composition with unique, distinct, and exclusive sugars. Using this method, a binder could potentially be evolved to that particular feature on Mtb. Chemical engineering professor Hadley Sikes develops paper-based diagnostic tools where the binding partner for a particular epitope or marker is laid down, and with the use of this discovery, in the longer term, a lateral flow assay device could be developed.

Laying the groundwork for future solutions

In cancer, certain sugars are overrepresented on cell surfaces, so theoretically, researchers can utilize this finding, which is also amenable to labeling, to develop a tool out of the evolved glycan binder for detection.

This discovery also stands to contribute significantly to improving cell imaging. Researchers can modify binders with a fluorophore using a simple ligation strategy, and can then choose the best fluorophore for tissue or cell imaging. The Kiessling group, for example, could apply small protein binders labeled with fluorophore to detect bacterial sugars to initiate fluorescence-activated cell sorting to probe a complex mixture of microbes. This could in turn be used to determine how a patient’s microbiome has been disturbed. It also has the potential to screen the microbiome of a patient’s mouth or their upper or lower gastrointestinal tract to read out the imbalance within the community using these types of reagents. In the more distant future, the binders could potentially have therapeutic purposes like clearing the gastrointestinal tract or mouth of a particular bacterium based on the sugars that the bacterium displays.

This article first appeared in MIT News. Read the original.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.