Early immune response may improve cancer immunotherapies

Viruses, bacteria and cancer have many ways to replicate and survive in our bodies. Viruses and bacteria invade a cell directly to avoid detection. Cancer cells have the advantage of being native in the body. However, the body has safeguards against such sneaky tactics.

In a paper published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, University of Illinois at Chicago researchers and colleagues report a new mechanism for detecting foreign material during early immune responses.

“There are proteins in the cell that await the presence of foreign material,” said Marlene Bouvier, senior author and UIC professor of microbiology and immunology at the college of medicine. “One protein, called endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1, or ERAP1, is programmed to find foreign material, like viral and bacterial proteins, and break it into smaller parts, also known as peptides. Another protein — major histocompatibility complex class I, or MHC I — is programmed to attach itself to a foreign peptide and move it to the cell’s surface. With the foreign peptide outside the cell, immune cells can recognize and destroy the infected cell.”

This is an example of a normal process, Bouvier said, but sometimes a foreign peptide, once bound to MHC I, remains in the cell. This happens when the foreign material is not broken down to a small enough size or is too long.

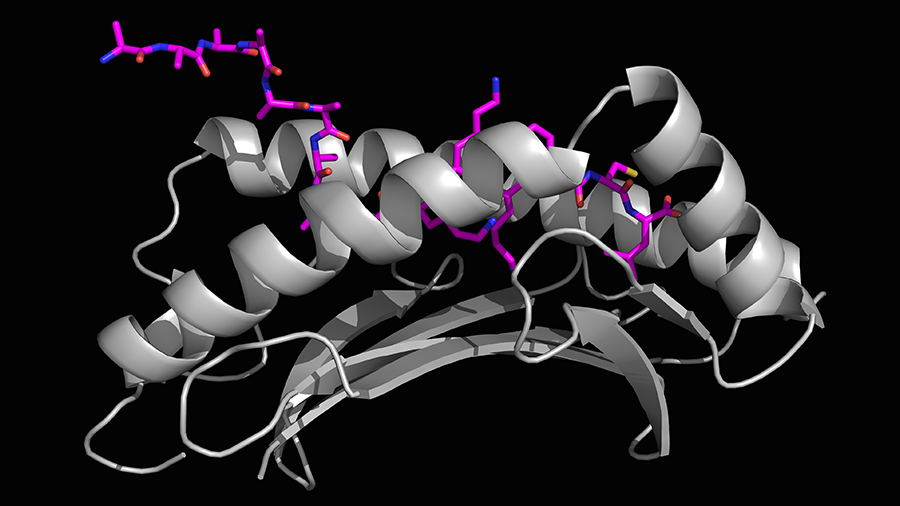

Bouvier and colleagues used X-ray crystallography (a method to see structures on an atomic level) and mass spectrometry (used to identify peptide length by mass) to show that ERAP1 can cut extra-long peptides even after they have bound to MHC I.

“X-ray crystallography allowed us to determine three-dimensional structures to see how these longer peptides bound to the MHC I groove with high resolution,” Bouvier said. “Using an ERAP1 enzymatic assay with mass spectrometry gave us the ability to show, for the first time, that ERAP1 can trim peptides bound to MHC I. These tools allowed us to develop a model of this new immune response mechanism.”

Bouvier said this new information may help researchers leverage ERAP1 to fight infections and cancer.

“This research can have major implications for immunotherapies,” she said. “For example, cancer cells do not always present enough peptides to be labeled as ‘foreign’ — allowing the cancer cells to replicate and grow. But if you have a way to manipulate how ERAP1 generates cancer peptides, then you can hopefully skew the peptide repertoire that is presented on the cell surface in our favor. This is the most translational application of our research.”

Lenong Li and Mansoor Batliwala from the department of microbiology and immunology in the UIC College of Medicine are co-authors on the paper.

This article originally was published by the University of Illinois at Chicago. It has been edited for ASBMB Today.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.