Do ribosomal traffic jams cause Huntington’s disease?

Huntington's disease, or HD, a genetic disorder that affects about one in every 10,000 people in the U.S., is inherited in an autosomally dominant manner, meaning that a person with the condition has a 50% chance of passing it on to their child. HD kills important neurons in the brain, causing uncontrollable movements and cognitive and psychiatric changes.

While scientists have long known that HD is caused by a cytosine–adenine–guanine trinucleotide repeat in the Huntingtin gene contained on chromosome 4, they are still studying the biological mechanisms that guide the disease process. In particular, researchers have implicated mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathophysiology of HD, and it is an ongoing focus of study.

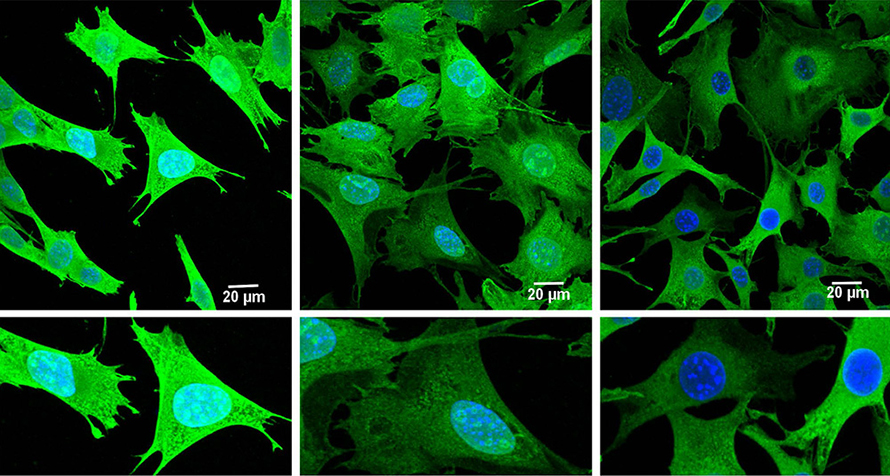

Investigators at the Wertheim University of Florida Scripps Research Institute recently used novel techniques to examine mRNA translation within the mitochondria of mice genetically altered to have HD. They found that ribosomes — particles responsible for creating proteins from instructions encoded in mRNA — get clustered and jammed on mitochondrial mRNA transcripts. The team published these new findings, in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

Srinivasa Subramaniam, an associate professor at Wertheim UF Scripps, was the lead author on the study. “Imagine going from Baltimore to Washington, D.C., and there are too many cars, and they are all jammed up,” he said. “Just because there are many cars does not mean they are all reaching their destination.

“So, what does that mean for the patient? That means that the patient may have difficulty translating their mitochondrial protein. And that may lead to problems in the assembly of these complexes, which may lead to problems in mitochondrial function.”

This project followed from Subramaniam’s previous work, which demonstrated high expression of fragile X messenger ribonucleoprotein, or FMRP, a protein that blocks ribosomes in HD. Consequently, he was curious to see the spatial distribution of ribosomes on mitochondrial mRNA, so Subramaniam turned to a technique called Ribo-Seq, which provides a snapshot of the location and density of ribosomes on a given mRNA transcript. He had no experience with the technique and immediately faced challenges.

“I am a biochemist by training,” Subramaniam said. “So I needed to sit and write hundreds of emails like ‘Can you help me?’ all over the world.”

He connected with collaborators in France and Ireland and took on a postdoc with Ribo-Seq experience. Almost four years later, Subramaniam and his lab published the results of their work. And with these results come new questions.

Previous research has shown that deleting the FMRP protein can prevent some cognitive deficits observed in HD. Subramaniam wants to investigate how modulating the expression of FMRP can affect the spatial distribution of ribosomes on mRNA transcripts. He also wants to see how communication between the cytoplasm and mitochondria contributes to what he likens to a "traffic jam." He hypothesizes that the cytoplasm inhibits proper functioning of mitochondrial mRNA, creating confusion.

“Imagine if you are traveling through a tunnel, and you close that tunnel,” he said. “Who puts on that brake? Who triggered that pathway? What is the signal that makes this traffic jam? That is what I want to know in more detail at the molecular level.”

He hopes this work has practical applications as well.

“How can we use small-molecule screening to reverse this phenotype?” he said. “My goal is to identify the mechanisms and then leverage potential therapeutics.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.