JBC: A spring-loaded sensor for cholesterol in cells

Researchers at the University of New South Wales have discovered that a spring-shaped protein structure senses cholesterol in cells.Courtesy of Andrew J. Brown, University of New South Wales Although too much cholesterol is bad for your health, some cholesterol is essential. Most of the cholesterol that the human body needs is manufactured in its own cells in a synthesis process consisting of more than 20 steps. Research from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, explains how an enzyme responsible for one of these steps acts as a kind of thermostat that responds to and adjusts levels of cholesterol in the cell. This insight could lead to new strategies for combating high cholesterol.

Researchers at the University of New South Wales have discovered that a spring-shaped protein structure senses cholesterol in cells.Courtesy of Andrew J. Brown, University of New South Wales Although too much cholesterol is bad for your health, some cholesterol is essential. Most of the cholesterol that the human body needs is manufactured in its own cells in a synthesis process consisting of more than 20 steps. Research from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, explains how an enzyme responsible for one of these steps acts as a kind of thermostat that responds to and adjusts levels of cholesterol in the cell. This insight could lead to new strategies for combating high cholesterol.

Toward the middle of the assembly line of cholesterol production, an enzyme called squalene monooxygenase, or SM, carries out a slow chemical reaction that sets the pace of cholesterol production. In 2011, Andrew Brown’s laboratory at UNSW discovered that when cholesterol in the cell was high, SM was destroyed and less cholesterol was produced. The new research explains how this process of sensing and destruction happens.

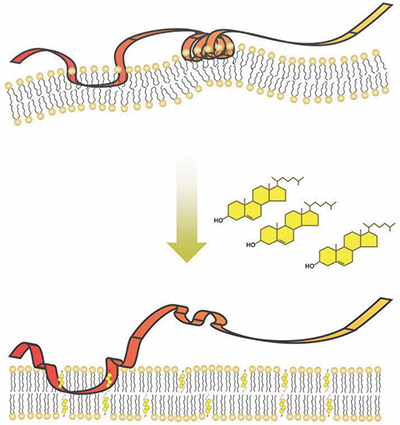

SM is embedded in the membrane of the cell’s endoplasmic reticulum, or ER, which is composed of fatty molecules, including cholesterol. As cholesterol in the cell increases, more and more of it is incorporated into the ER membrane.

SM contains a series of 12 amino acids that serve as a “destruction code” that tells the cell’s garbage disposal machinery to degrade the SM protein. Brown’s team showed that under typical conditions, the destruction code is hidden by being tucked away inside the ER membrane as part of a spring-shaped structure. Using experiments in cell cultures and with isolated proteins and membranes, they also showed that this spring structure could embed only in membranes that contained a low percentage of cholesterol. When the amount of cholesterol making up the membrane increased, the spring popped out, exposing the destruction code.

Ngee Kiat Chua, a graduate student, led the new study. “When cholesterol levels are low, this destruction code is hidden in the membrane like a spring-loaded trap,” Chua said. “However, too much cholesterol (in the membrane) springs the trap, unmasking the destruction code.”

When this occurs, the cell proceeds to destroy the SM.

The researchers speculate that, because the synthesis step carried out by SM is crucial to determining the amount of cholesterol a cell produces, drugs targeting SM could be used to decrease cholesterol as an alternative to the oft-prescribed statins, which target an enzyme earlier in the cholesterol synthesis assembly line. But they also wonder whether the type of cholesterol-responsive spring they discovered might be used by other proteins involved in cholesterol metabolism to sense and adjust cholesterol levels.

“It’s perhaps stretching the bow a little too far to make a connection from our little cholesterol spring mechanism to metabolic disorders,” Brown said. “But we’ve found a fundamental cholesterol-sensing mechanism, and that’s where this work has advanced the field.”

Sasha Mushegian is scientific communicator for the Journal of Biological Chemistry. Follow her on Twitter.

Sasha Mushegian is scientific communicator for the Journal of Biological Chemistry. Follow her on Twitter.Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)