UTSW researchers discover how food-poisoning bacteria infect the intestines

Researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center have discovered how a bacterium that infects people after they eat raw or undercooked shellfish creates syringe-like structures to inject its toxins into intestinal cells. The findings, published in Nature Communications, could lead to new ways to treat food poisoning caused by Vibrio parahaemolyticus.

“We have provided the first visual evidence of how a gut bacterial pathogen uses this assembly method to build a syringe to deliver a lethal injection to intestinal cells,” said Kim Orth, a professor of molecular biology and biochemistry and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator at UTSW. “This work provides a new view of how enteric bacteria when exposed to bile acids efficiently respond and build a virulence system.”

V. parahaemolyticus, commonly found in warm coastal waters, is a leading cause of seafood-related food poisoning. People infected often have diarrhea, cramping, vomiting, fever and chills.

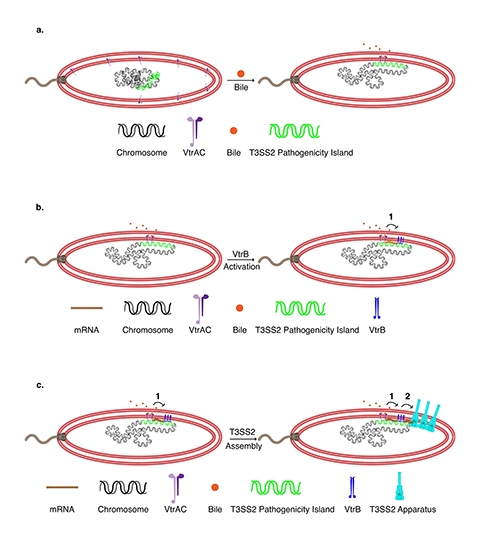

Researchers knew that V. parahaemolyticus injects molecules into human cells using a structure called the type III secretion system 2 (T3SS2). However, these syringes, composed of 19 different proteins, are not produced or assembled until the bacteria are inside the intestines. Scientists were not sure exactly how this occurs.

The latest findings build on the work of a previous study by the Orth lab. Orth and her colleagues tagged components of the V. parahaemolyticus T3SS2 with fluorescent markers and used super-resolution microscopy to track their locations as the bacteria were grown in different conditions. The researchers discovered that when V. parahaemolyticus is exposed to bile acids — digestive molecules in the intestines — the bacteria move DNA containing the T3SS2 genes close to their membrane.

Then, at the exact site where the T3SS2 is needed, V. parahaemolyticus transcribes that DNA into RNA, translates the RNA into protein, and assembles the components of the T3SS2 through the membrane in a process known as transertion. “It is like watching the assembly of a factory that produces a large molecular machine within an hour,” Orth said.

These steps were previously thought to occur in more disparate locations around a cell, but pulling the machinery together into one place on the bacterium’s membrane likely helps V. parahaemolyticus more quickly and efficiently build the T3SS2 and infect cells. Since other disease-causing gut bacteria contain molecular components similar to V. parahaemolyticus, the phenomenon of transertion may be widely used, the researchers hypothesize.

“Our findings imply that other gastrointestinal pathogens may also use this mechanism to mediate efficient assembly of complex molecular machines in response to environmental cues,” said UTSW research specialist Karan Kaval, first author of the paper.

More work is needed to know which bacteria use transertion to build their T3SS structures and whether drugs could be developed that block transertion to treat V. parahaemolyticus infections.

UTSW researcher Jananee Jaishankar also contributed to this study.

This article was first published by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Read the original.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.