Revealing what makes bacteria life-threatening

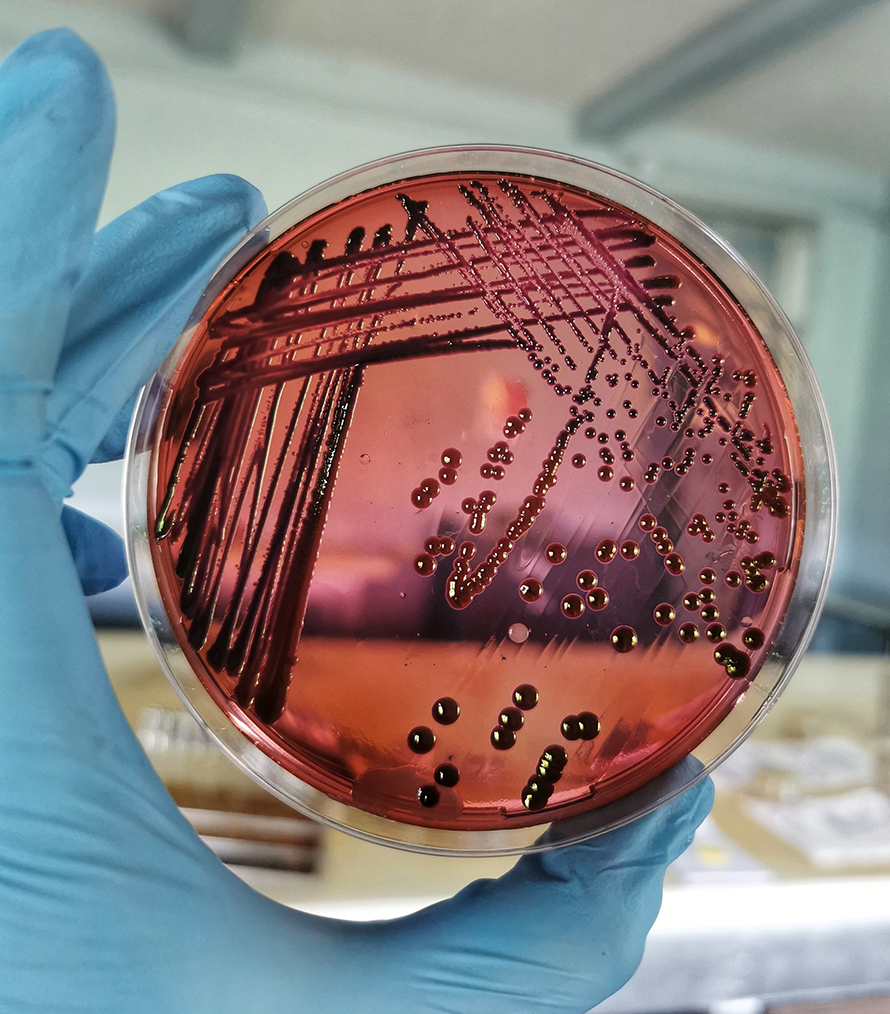

Queensland researchers have discovered that a mutation allows some E. coli bacteria to cause severe disease in people while other bacteria are harmless, a finding that could help to combat antibiotic resistance.

Professor Mark Schembri and Dr Nhu Nguyen from IMB and Associate Professor Sumaira Hasnain from Mater Research found the mutation in the cellulose making machinery of E. coli bacteria. The research was published in Nature Communications.

Professor Schembri said the mutation gives the affected E. coli bacteria the green light to spread further into the body and infect more organs, such as the liver, spleen and brain.

"Bad' bacteria can't make cellulose

“Our discovery explains why some E. coli bacteria can cause life-threatening sepsis, neonatal meningitis and urinary tract infections (UTIs), while other E. coli bacteria can live in our bodies without causing harm,” Professor Schembri said.

“The ‘good’ bacteria make cellulose and ‘bad’ bacteria can’t.”

Bacteria produce many substances on their cell surfaces that can stimulate or dampen the immune system of the host.

Inflammation and spreading through the body

“The mutations we identified stopped the E. coli making the cell-surface carbohydrate cellulose and this led to increased inflammation in the intestinal tract of the host,” Professor Schembri said.

“The result was a breakdown of the intestinal barrier, so the bacteria could spread through the body.”

In models that replicate human disease, the team showed that the inability to produce cellulose made the bacteria more virulent, so it caused more severe disease, including infection of the brain in meningitis and the bladder in UTIs.

Finding new ways to prevent infection

Associate Professor Hasnain said understanding how bacteria spread from intestinal reservoirs to the rest of the body was important in preventing infections.

“Our finding helps explain why certain types of E. coli become more dangerous and provides an explanation for the emergence of different types of highly virulent and invasive bacteria,” she said.

Professor Schembri said E. coli was the most dominant pathogen associated with bacterial antibiotic resistance.

“In 2019 alone, almost 5 million deaths worldwide were associated with bacterial antibiotic resistance, with E. coli causing more than 800,000 of these deaths,” he said.

“As the threat of superbugs that are resistant to all available antibiotics increases worldwide, finding new ways to prevent this infection pathway is critical to reduce the number of human infections.”

This article was republished from the University of Queensland website. Read the original here.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.