Progesterone from an unexpected source may affect miscarriage risk

About 20% of confirmed pregnancies end in miscarriage, most often in the first trimester, for reasons ranging from infection to chromosomal abnormality. But some women have recurrent miscarriages, a painful process that points to underlying issues. Clinical studies have been uneven, but some evidence shows that for women with a history of recurrent miscarriage, taking progesterone early in a pregnancy might moderately improve these women’s chances of carrying a pregnancy to term.

A recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research sheds light on a new facet of progesterone signaling between maternal and embryonic tissue. The work hints at a preliminary link between disruptions to this signaling and recurrent miscarriage.

Progesterone plays an important role in embedding the placenta into the endometrium, the lining of the uterus. The hormone is key for thickening the endometrium, reorganizing blood flow to supply the uterus with oxygen and nutrients, and suppressing the maternal immune system.

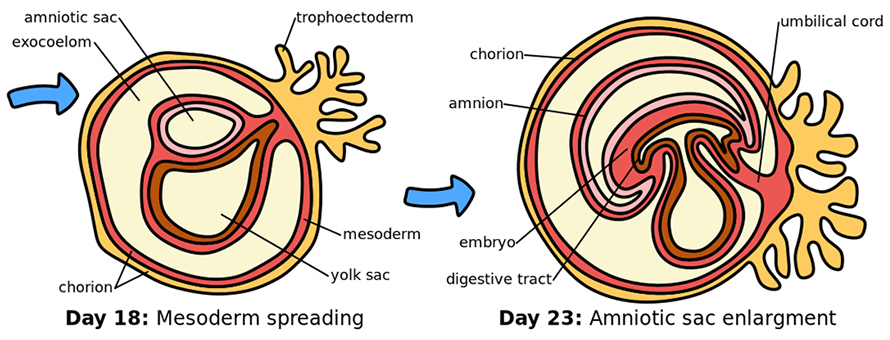

Progesterone is made in the ovary as a normal part of the menstrual cycle, and at first, this continues after fertilization. About six weeks into pregnancy, the placenta takes over making progesterone, a critical handoff. (The placenta also makes other hormones, including human chorionic gonadotropin, which is detected in a pregnancy test.) Placental progesterone comes mostly from surface tissue organized into fingerlike projections that integrate into the endometrium and absorb nutrients. Some cells leave those projections and migrate into the endometrium, where they help to direct the reorganization of arteries.

Using cells from terminated pregnancies, Austrian researchers led by Sigrid Vondra and supervised by Jürgen Pollheimer and Clemens Röhrl compared the cells that stay on the placenta’s surface with those that migrate into the endometrium. They discovered that the enzymes responsible for progesterone production differ between those two cell types early in pregnancy.

As a steroid hormone, progesterone is derived from cholesterol. Although the overall production of progesterone appears to be about the same in migratory and surface cells, migratory cells accumulate more cholesterol and express more of a key enzyme for converting cholesterol to progesterone. Among women who have had recurrent miscarriages, that enzyme is lower in migratory cells from the placenta than it is among women with healthy pregnancies. In contrast, levels of the enzyme don’t differ between healthy and miscarried pregnancies in cells from the surface of the placenta.

The team’s findings suggest that production of progesterone by the migratory cells may have a specific and necessary role in early pregnancy and that disruption to that process could be linked to miscarriage.

“If we can identify the exact mechanisms and cells that are affected,” Vondra said, “that would lead us one step closer to understanding the big picture of what causes recurrent miscarriages and possibly to being able to intervene and allow these women to have successful pregnancies.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Fasting, fat and the molecular switches that keep us alive

Nutritional biochemist and JLR AE Sander Kersten has spent decades uncovering how the body adapts to fasting. His discoveries on lipid metabolism and gene regulation reveal how our ancient survival mechanisms may hold keys to modern metabolic health.

Redefining excellence to drive equity and innovation

Donita Brady will receive the ASBMB Ruth Kirschstein Award for Maximizing Access in Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Mining microbes for rare earth solutions

Joseph Cotruvo, Jr., will receive the ASBMB Mildred Cohn Young Investigator Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Fueling healthier aging, connecting metabolism stress and time

Biochemist Melanie McReynolds investigates how metabolism and stress shape the aging process. Her research on NAD+, a molecule central to cellular energy, reveals how maintaining its balance could promote healthier, longer lives.

Mapping proteins, one side chain at a time

Roland Dunbrack Jr. will receive the ASBMB DeLano Award for Computational Biosciences at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.